Since the US removed exemptions that allowed eight countries — including Japan, China and South Korea — to import Iranian oil, sanctions on Tehran have really begun to bite, and the threat to commercial shipping in the strategic Strait of Hormuz has increased in proportion.

The European signatories to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the 2015 agreement to curb Iran’s nuclear program in return for the easing of sanctions, have been trying to keep it alive. Their attempt to devise a non-dollar payment channel so that European companies could still trade with Iran has not been a stellar success. European companies face a dilemma: Do business with Iran, whatever the payment mechanism, and you will be frozen out of the world’s largest economy. The US sanctions have come at some cost to several European companies who had started doing business with Iran after the JCPOA came into force; the French energy giant Total, for instance had to write off a $1billion investment in the South Pars field.

In response to the US campaign of “maximum pressure” aimed at reducing Iran’s oil exports to zero, the regime in Tehran threatened that if they could not export oil, no Gulf state would. Since then, six tankers in the Gulf have been sabotaged and drones launched by the Iran-backed Houthi militia in Yemen damaged two pumping stations on Saudi Aramco’s strategic East-West Pipeline. In the light of its previous threat, Iran’s denials of involvement in any of this have been greeted with skepticism.

Tension increased by several notches two weeks ago when the Iranians shot down a US drone and only narrowly escaped retaliatory US missile strikes. Then, in early July, the UK confiscated the Iranian tanker Grace 1 carrying a million barrels of oil to Syria in breach of EU sanctions against the Assad regime. Iran described the seizure of the vessel by Royal Marines off the coast of Gibraltar as an act of piracy, but the UK was within its legal rights. Later that week Iran tried to block the passage of the BP-owned tanker British Heritage through the Strait of Hormuz. That attempt was thwarted when the British frigate HMS Montrose drove off the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) gunboats, its weaponry trained on them. Then the US said it had shot down an Iranian drone, which Tehran denied. In the latest twist, the IRGC have confiscated the UK-flagged oil tanker Stena Impero. Jeremy Hunt, the foreign secretary and a Tory leadership contender, condemned Iran’s actions in the strongest terms, but indicated that Britain would prefer a diplomatic solution to a military one.

The world has every interest in the Strait of Hormuz staying open. Nobody wants to see yet another military confrontation in the region.

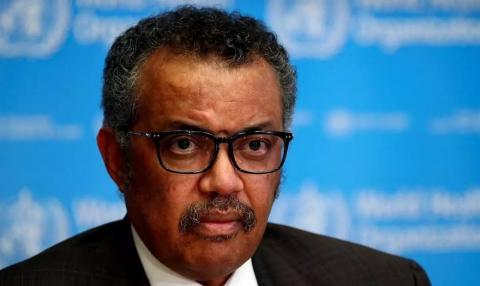

Cornelia Meyer

This all looks like the script for an action film or a war movie, but sadly it is a great deal more serious. The Strait of Hormuz is one of the world’s most vital waterways. About 17 million barrels of oil are transported through it every day, more than a third of the world’s seaborne oil shipments and a fifth of oil traded worldwide. That makes it important to Gulf Cooperation Council oil producers and Asian consumers alike. India, China, Korea, Taiwan and Japan depend on open sea lanes for the security of their oil and liquefied gas supplies. The economic dimension is as significant as the strait’s geographic location. The Middle East is a sea of conflict, in which the GCC is the only island of stability. It is unwise to light matches when sitting in a tinder box; you could easily start a blaze, and the last thing the region needs is another conflict.

The question is, how to de-escalate the tensions? The Europeans have tried to keep the JCPOA alive, attempts helped neither by Iran’s recent maritime actions nor by Tehran breaching the JCPOA in terms of uranium enrichment and storage. The confiscation of Stena Impero may well have been the last nail in the coffin of the 2015 deal.

US President Donald Trump, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Brian Hook, the US special representative for Iran, have for some time advocated the formation of an international coalition to protect commercial passage through the Arabian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz. Given that most Gulf oil is bound for Asia, they have also asked for financial burden sharing.

Adm. Lord West of Spithead, the distinguished former British security minister who was head of the Royal Navy from 2002 to 2006, believes such plans should have been acted on before now; and that the best way to de-escalate the situation is to create convoys of commercial ships escorted through the strait by warships. He makes a good point, because tensions rise with every incident. Take the incidents away and over time things may calm down.

By now, America’s European NATO allies are most likely to stand ready to send their frigates. It will be more difficult for the Japanese, because their constitution limits overseas operations by their forces. Nor will the Americans be eager to give Chinese naval vessels access to that part of the Middle East; they are too concerned about Beijing’s geopolitical expansion, whether in the South China Sea or with the Belt and Road Initiative.

All in all, the world has every interest in the Strait of Hormuz staying open. Nobody wants to see yet another military confrontation in the region. Anything that can de-escalate the tensions is welcome. Lord West’s convoys may serve that objective by preventing further incidents.