ver the phone last Thursday I spoke to Tayjay, a 24-year-old man being held in Colnbrook detention centre. Tayjay has lived in the UK since he was five, as was obvious when I heard his strong London accent. His life is deeply entwined with his family, all of whom live in the UK. Most days, he takes his younger brother to school.

Tayjay told me he was the victim of county lines grooming and compelled to carry drugs. This resulted in a single drugs-related offence and a 15-month conviction, for which he served seven months in 2015, when he was 19. Since he was released five years ago, despite never reoffending, Tayjay has been terrified of being deported. He has only visited Jamaica once before and said even then he found it “too hot” and “wanted to come home”.

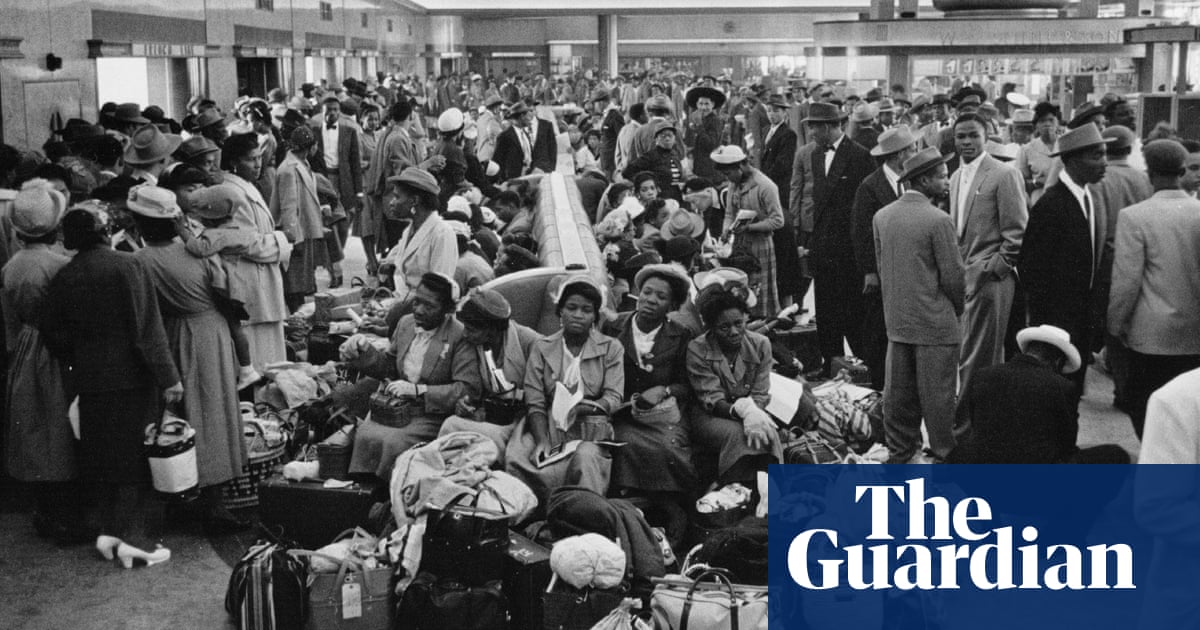

Like Tayjay, many of those scheduled to be deported on tomorrow’s charter flight to Jamaica are more British than they are Jamaican. It is impossible to get a complete picture of who will be in the final 50, as there is no transparency from the Home Office, but I know of at least five people who arrived in the UK as children as young as two, five, seven and 11. I know of one man who was born in the UK to a Windrush generation mum. Six detainees had indefinite leave to remain in the UK – and a number of them could have received British citizenship as children but were unable to afford the high fees.

If this flight goes ahead, at least 41 British children will be deprived of their fathers. What problems will this create in their own lives? And who exactly is splitting up families supposed to help?

I served my time in prison. So why am I being deported?

Michael McDonald

Read more

Every single one of the men has already served the sentence the judge deemed appropriate for their crime. Each has endured additional time in immigration detention centres. And now these men will receive a third punishment – complete ostracisation from their communities – which in some cases could become a death sentence. The Guardian revealed that at least five people had been killed after being deported to Jamaica since the Windrush scandal was exposed.

Regardless of criminal convictions, it is a breach of human rights legislation to deport individuals to a country where their lives could be in serious danger.

The echoes of Windrush are deafening, just two years after this national scandal was exposed. The Home Office admitted that it wrongly deported or detained at least 164 black British citizens and probably many more. At least 11 of them died on the streets of foreign countries where they were deported.

There are more than 5,000 cases of individuals alleging that they were in some way seriously harmed – made homeless, jobless, left destitute and denied access to public services – by the government that was supposed to protect them.

After the government admitted its crimes against these British citizens in 2018, it rightly suspended deportation flights to the Caribbean and set up an independent review, headed by Wendy Williams, to ensure lessons were learned. The Windrush Lessons Learned review was first due to be published on 31 March last year. It was then delayed to September. It still hasn’t appeared.

Guardian Today: the headlines, the analysis, the debate - sent direct to you

Read more

How can we be confident the Home Office is not repeating the same mistakes before it has published, let alone implemented, its own review? All it took was two years of lying low, and now the “deport first, ask questions later” policy has returned.

Last week I leaked part of a draft of the Windrush Lessons Learned review because it confirmed my worst fears.

Boris Johnson’s government is suppressing its own independent review so it can knowingly and intentionally defy the recommendations that are made within it. In it, Wendy Williams says the government should “review its policy and approach to FNOs [foreign national offenders], if necessary through primary legislation”. These include considering “ending all deportation of FNOs where they arrived in the UK as children” and only using deportation in “the most severe cases”. When I asked a question about the flight in parliament today, the Home Office minister Kevin Foster said I was “losing the plot”, and the Tory MP Suella Braverman accused me of “shrill virtue signalling”.

There should be no more deportation flights until the Windrush Lessons Learned review is published and its recommendations implemented. I accept there may be some cases where the most severe violent criminals, who came to the UK as adults, should face the prospect of deportation. However, to enforce this policy on those who have lived in the UK since they were children, as well as those who have committed one-off drugs offences, is wildly disproportionate and cruel.

The government’s decision to ignore the recommendations shows it is not sorry. It has little regard for the lives it has ruined, and will keep making the same mistakes. Much of this is because it still fails to confront the legacy of empire. The UK and Caribbean are entwined because the British empire enslaved black Africans and brought them there in shackles on slave ships. Lives are being ruined because we don’t remember our history.

Advertisement

• David Lammy is the Labour MP for Tottenham

As 2020 begins…

… we’re asking readers, like you, to make a new year contribution in support of the Guardian’s open, independent journalism. This has been a turbulent decade across the world – protest, populism, mass migration and the escalating climate crisis. The Guardian has been in every corner of the globe, reporting with tenacity, rigour and authority on the most critical events of our lifetimes. At a time when factual information is both scarcer and more essential than ever, we believe that each of us deserves access to accurate reporting with integrity at its heart.

You’ve read 14 articles in the last four months. More people than ever before are reading and supporting our journalism, in more than 180 countries around the world. And this is only possible because we made a different choice: to keep our reporting open for all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay.

We have upheld our editorial independence in the face of the disintegration of traditional media – with social platforms giving rise to misinformation, the seemingly unstoppable rise of big tech and independent voices being squashed by commercial ownership. The Guardian’s independence means we can set our own agenda and voice our own opinions. Our journalism is free from commercial and political bias – never influenced by billionaire owners or shareholders. This makes us different. It means we can challenge the powerful without fear and give a voice to those less heard.

None of this would have been attainable without our readers’ generosity – your financial support has meant we can keep investigating, disentangling and interrogating. It has protected our independence, which has never been so critical. We are so grateful.

As we enter a new decade, we need your support so we can keep delivering quality journalism that’s open and independent. And that is here for the long term. Every reader contribution, however big or small, is so valuable. Support The Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.