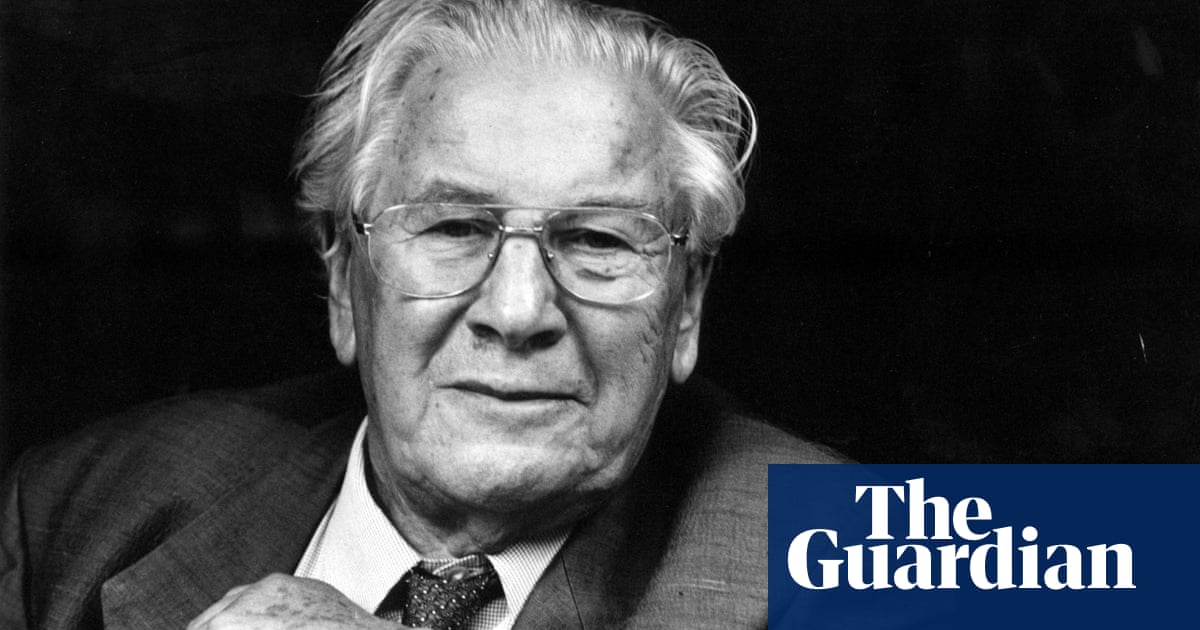

ou may not know the name John Langdon, who died on 23 March, but you’ll very probably have laughed at his jokes or even read his pun-packed posters on the London Underground in the 1980s. When the story of BBC Radio Light Entertainment is written, the legend of Langdon will feature large, not least because he wrote the famous Week Ending sketch about Derek Jameson (“a man who thinks erudite is a type of glue”) for which the tabloid editor sued the BBC and lost. But to me, he was my best friend, my greatest encourager and, for over 35 years, my constant writing partner.

He’d appreciate the irony of now being the late John Langdon, as that was a salient part of his reputation – his inability to deliver scripts on time, or rather, his infallible ability to produce far too many jokes at the very last minute. “Do you want it funny or do you want it Friday?” he’d say, knowing that producers invariably wanted it Friday. But he, equally invariably, managed, through a combination of chaotic genius and perfectionism, to push it into the small hours of Saturday. One producer blamed the break-up of his marriage on the fact that his wife wouldn’t believe him when he insisted he was working late editing John’s scripts and decided he must be having an affair. Barry Cryer would say John was like Brigadoon, the Scottish village that appeared out of the mist one day every 100 years.

In the 80s John was a writer on the radio corridor at the BBC, working on weekly satirical shows such as Week Ending and The News Quiz with writers including Dave Cohen, Pete Sinclair, Andy Hamilton and Jeremy Hardy. I think it was Pete or Dave who credited John with “the Langdon”, a joke formula where you introduce two subjects, and switch them at the punchline. For example, Boris Johnson and his girlfriend introduced their new dog to Downing Street yesterday. “He’s a bit scruffy and wants to shag everything that moves, but we’ll get used to him,” said the dog.

He wrote whole series of The News Quiz – in the Barry Took/Simon Hoggart era - on his own (now there are often three or four credited writers) – usually, as was his style, outside on the pavement, leaning against railings so he could smoke unusual cigarettes and type on a handheld computer or scribble on sheets of paper. Someone contacted me this week to say he remembered John going AWOL while working on Frankie Howerd’s TV show. They found him in a cubicle in the gents’ writing material on a “bakelite microwriter contraption” strapped to his thigh.

We were paired up in Edinburgh in 1984. I was doing my first standup show, with Mark Steel and Jenny Eclair, and BBC radio producers Alan Nixon and Jennie Campbell wanted to use my impressions to link highlights from the rest of the Fringe. Jennie introduced us and from that day forward, we were inseparable.

Yes, the scripts could be overwritten, a torrential flow of jokes that I told him were like those Indian trains with people hanging off every conceivable door and window. But he taught me everything I know about writing, and as I grew more confident and self-reliant (because sometimes it had to be Friday) he became the best editor and embellisher of my efforts I could wish for. We ended up like a married couple, finishing each other’s sandwiches. (A typical John twist, that. A couple “finishing each other’s sentences” wouldn’t be funny. Unless, like Jack Dee, you make the couple Fred and Rosemary West.)

Just weeks before John died, we were writing lines for the tour of I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue and one of our last email exchanges crossed in the ether. Inventing new slogans for companies, we’d each written, unbeknown to the other, “SussexRoyal.com: Heir today, gone tomorrow.”

However good the line, he’d want to make it even better. Asked by Stephen Fry to do a piece at Prince Charles’s 50th, I suggested Dr Dolittle singing, “If I could talk to the vegetables”. (“Imagine talking to a turnip; moaning to a mushroom – I could even talk in Swedish – to a Swede!” ) Back came the lines from John: “I’d frater-nize with whole fields of wheat / bend their ears a bit / it’s a-MAIZE-ing just how corny I can be; I love to share a hearty joke / with an audience of artichoke / I’m a sort of life and soul of the party bloke / and they all talk to me.” There’s the joy of writing together, right there.

Late as he was with scripts, he could be lightning fast with one-liners. Backstage at a Prince’s Trust gala, the great Robin Williams asked him: “What do you say to a prince?” John immediately suggested: “I’m a great fan of yours – I’ve got all your portraits.” Someone once remarked that they hadn’t realised Barry Took was so tall. “That’s because he’s standing on Marty Feldman’s reputation,” John replied. Very unfair, as John immediately acknowledged, but boy, it was quick.

Friday nights on Bremner, Bird and Fortune were the best. John and I would madly rewrite my opening monologue as I sat in the make-up chair, with the warm-up comedian already priming the studio audience. With five minutes to go, John would run to give the changes to our long-suffering autocue operator Sarah. As I was introduced with a cheer from the audience, John would jump up and down mouthing “Kill! Kill! Kill!” as I bounded to the microphone and did a few minutes warm-up of my own while the script was typed into the autocue in front of me. When it was finished, I’d sight-read it, humming the voices instead of actually speaking, and then we’d run the opening titles and start recording.

That was how we did it. It was all adrenaline, seat-of-the-pants, last-minute writing stuff.

Beyond writing, John was the kindest, most generous, least judgmental man you could ever meet. Such was his love of other people that he was the least important person in his life – this often extending to his appearance. Once he arrived on set with severe toothache. I sent him off to the dentist. John came back later that day having had all his top teeth removed, unable to control his top lip or speak as the anaesthetic hadn’t worn off. For months he didn’t have any false teeth fitted, chewing everything – even sandwiches – with his gums, his lack of teeth hidden under his trademark moustache.

A while ago, we lost contact for a year or two. I found out it was because he’d been unwell and didn’t want to tell me, as he knew I’d want to put it right, and it couldn’t be put right. In those years he slipped into reclusiveness, editing a magazine about sewing machines of which he became, by default, a huge collector. Luckily we got back in touch and in his final years he wrote wonderful material for me and for Jan Ravens, driven to one show by his devoted wife Ros and carrying his own oxygen supply, the result of the COPD that was ultimately to claim his life.

He was writing up to a few weeks before his final relapse, living on oxygen, having lost sight in one eye and having a cataract in the other. There wasn’t a shred of self-pity. He knew his time was up and he’d had an extraordinary, unconventional, complicated, fulfilling life. It was our greatest luck – all of us who worked with him on our shows – that we shared so much of that life with him, doing what we all loved. Making comedy. Oh, how we’ll miss him.