t’s 1992, and two lowriders walk into a Penthouse Players record release party at the Hollywood Athletic Club. They did not arrive together, but as two of the only Chicanos at the party, they were quickly introduced. Both steeped in the 1990s hip-hop zeitgeist, they bond over music, art and the beloved Los Angeles pastime of custom lowrider cars. Bedazzled in intricately designed, glinting candy paint with wire-spoke wheels, whitewall tires and bouncing hydraulics, a lowrider isn’t just something you own, it’s something you are.

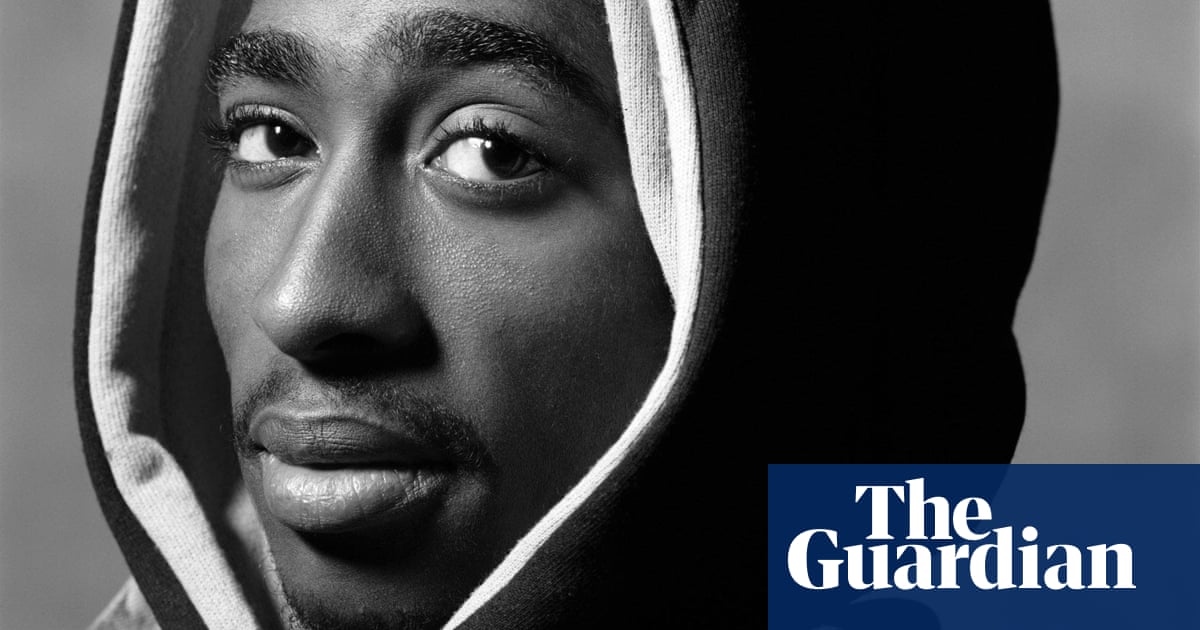

Estevan Oriol and Mister Cartoon (née Mark Machado) are born and bred Angelenos – Oriol from West LA and Cartoon from San Pedro. They lived similar yet separate lives until 1992, when their paths collided and their ascension to hip-hop eminence began, explored in detail in the new Netflix documentary LA Originals.

“The world’s kind of small in lowrider culture,” says Cartoon, who was given his nickname in high school because of his animated personality. “I didn’t know what networking was but that’s what I was doing when I met Estevan at a record release party I had done the cover art for. When I found out he was a lowrider too, we instantly connected.”

Growing up in south Los Angeles, Cartoon seamlessly transitioned between various creative endeavors. Discovering a preternatural skill for drawing at a young age, his parents – who owned a lithograph printing company – wholeheartedly supported his craft, emboldening him to pursue a career in art. What began with pen on paper soon evolved to spray paint on walls, airbrush on T-shirts and prints on paper before finally arriving at ink on skin.

In addition to designing the logos for Cypress Hill and Eminem’s Shady Records, Cartoon has etched the hides of pop culture royalty such as B-Real, Kobe Bryant, Eminem, 50 Cent, Travis Barker, Justin Timberlake, Beyoncé, Danny Trejo and Snoop Dogg, some of whom are featured in the film. His style became iconic because he was one of the first artists to diverge from the ever-popular flash style of tattoo, wherein a numbered series of traditional designs hung on the wall that patrons picked on the spot. Cartoon’s tattoos were – and still are – custom, seminal and distinct. Fusing his Mexican heritage, lowrider aesthetics and hip-hop culture with the fine-line style of tattoo art that was born in California prisons, he quickly found a niche

“The tattoo world is different from any other art form,” says Cartoon. “In every other style of art, especially graffiti, if you take somebody’s shit, you’re a biter, you stole it. With tattooing, you can borrow anybody’s artwork and put it on as a tattoo because you don’t sign them – it’s all borrowed, inspired by other cultures and artists and combined with the tattoo artist’s own style.”

Though Cartoon’s most well known canvas is skin, one can also marvel at his latest mural painted on the exterior of the Chicano landmark Casa Vega, a family-owned, historic Mexican restaurant located in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles. Open since 1956, Casa Vega is a local institution that has seen patrons such as Marlon Brando and Quentin Tarantino in its glossy, tufted red booths.

Meanwhile, in West LA, Oriol was living a parallel existence. The son of renowned activist, artist and photographer Eriberto Oriol, he was genetically predisposed to living the life of a creative. Though lowrider culture was his passion, he found work as a bouncer for a hip-hop club. It was there he became a friend to a clique of hip-hop pioneers which eventually led him to becoming a tour manager for Cypress Hill and House of Pain

Nearing the eve of his launch into the rap touring world, his father gave him a gift that, unbeknown to Estevan at the time, would reroute the trajectory of his life.

“The first camera I got was a Minolta 35mm,” Oriol, who also directed the documentary, reflects. “It was given to me by my dad and was his spare camera. He was also a photographer, but was kind of over photography by that time. He said, ‘Hey man, I got this extra camera. You’re doing your lowriding stuff and going on tour with House of Pain so you should take pictures of all that.’”

“I started out real slow, taking pictures of my people in the lowrider community, then also of House of Pain,” Oriol continues. “At first, I felt really uncomfortable bringing out a camera and putting it in people’s faces but after a while I started getting used to it and it became easier. I was the only person taking photos on these tours at the time.”

What began as capturing moments for posterity became a full-blown career. Since touring with House of Pain and Cypress Hill nearly 20-years ago, Oriol has become a photography heavyweight, his work often showcasing the gritty microcosms of LA that are diametrically opposed to the Hollywood glamour often projected to the world at large. Additionally, he has directed several music videos making him as much a fixture of the hip-hop community as the rappers themselves.

Oriol’s photography portfolio boasts an impressive lineup of athletes, artists, celebrities, and musicians alongside his unpolished, often black-and-white captures of Skid Row’s homeless community as well as Latinx, gang, and tattoo cultures. He has photographed rap deities such as Dr Dre, Cypress Hill, Ice Cube, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Big Pun, Rick Rubin and the Beastie Boys, as well as the portraits of Al Pacino, Dennis Hopper, Robert De Niro and Floyd Mayweather. Still a lover and champion of film photography, Oriol’s work shows that in Los Angeles, glamour and grit are not mutually exclusive.

One of Oriol’s most recognizable photos is the so-called LA Fingers. It features a woman’s hands, adorned with long angular talons and ornate rings, forming an L with the index finger and thumb on one hand and an A with the index and middle fingers on the other. “I wasn’t the first one to throw up the sign, but I can confidently say that I was the first one to capture it in a photo,” Oriol told Los Angeles Magazine in an article about the famed image.

It has since been copied, mass produced and turned into clip art in several forms – from T-shirts to coffee mugs. In 2013, Oriol sued clothing retailers H&M and Brandy Melville, which used the image without his permission. According to Oriol, the judge ruled that a hand gesture cannot be trademarked by comparing it to the peace sign. Another finger gesture comes to mind, but the peace sign is the more diplomatic choice for comparison, despite the unfortunate ruling of the case.

When Oriol and Cartoon finally merged their creative psyches, a super duo was formed. Though both were successful apart, together they created an empire. After Oriol made Cartoon his first tattoo gun, out of a Walkman motor and a Bic pen, taught to him by a friend who made one in prison, Cartoon’s career flourished.

They went on world tours with hip-hop giants, photographing and tattooing them along the way. They established a creative agency called Soul Assassins that was unfortunately shuttered shortly after the market crash in 2008. They partied, they hustled, they traveled, they created, they never stopped lowriding, and now, they’ve made a documentary about it all. One of the most important tenets of their ethos, however, which is scarcely publicized is their community outreach.

“We are always helping out the community, we just don’t publicize it,” Oriol explains. “We’re not doing it for a pat on the back, we’re doing it more because I have family members who have been homeless and friends and family members that were drug addicts. I donate my time, I donate clothes, I donate money, I donate food to homeless people and mentally ill people. And now also, we give jobs to convicted felons who can’t find work.”

“We’ve been doing outreach in schools for 20 years also,” Cartoon adds. “We didn’t show that in the movie, ‘cause it’s just what we do. We don’t film it too often, you know, but one artist helping another is a powerful thing.”

LA Originals is available on Netflix on 10 April