When American astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley arrive at the International Space Station this week, they will find an unusual message waiting for them. On the inside of the hatch where their SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft is scheduled to dock, a small stars and stripes flag has been sealed in a plastic bag with a cryptic message attached. “Flown on STS-1 and STS-135. Only to be removed by a crew launched from KSC.”

It sounds enigmatic but the meaning is straightforward. The flag, which measures 8 inches by 12 inches, was flown on board the first space shuttle mission (STS-1) in 1981. And it was carried aloft in 2011 when the shuttle Atlantis rendezvoused with the space station on the last shuttle mission (STS-135). KSC simply stands for the Kennedy Space Centre.

Departing astronauts on Atlantis had left the flag and message before flying their craft back to the US, where it was grounded with the other remaining shuttle craft in the wake of the Challenger and Columbia tragedies. Only when Americans returned – in a new fleet of their own spaceships – was that flag to be brought back to Earth, it was decreed.

Now that moment is about to arrive. After a gap of nine years, during which US astronauts have had to undergo the ignominy of hitching rides to the space station in Russia’s cramped Soyuz space capsules, American men and women are set to return to orbit in their own craft – in this case, Elon Musk’s SpaceX Crew Dragon spaceship.

It will be a triumphant moment for America as it enters a new stage in its often troubled manned space programme. Crewed spaceflights into low Earth orbit will now be taken over by private businesses which have already been ferrying supplies to the space station. To date, only the governments of America, Russia and China have been able to mount manned space programmes. Now US business is taking a lead.

“It’s an important moment, not just for the US but for all the other national groups involved in the space station,” said Frank De Winne, head of the European Space Agency’s astronaut centre in Cologne. “We will be able to have a full compliment of seven astronauts on the station. At present, there are only three because transport has been limited. Crew Dragon means we can get back up to strength and catch up with all the science that we couldn’t do for lack of personnel.”

Putting astronauts into orbit has always been costly and has bedevilled efforts to open up space as a commercial frontier. Nasa had developed a strong risk aversion policy, which meant its vehicles were more complex than necessary, and a lack of competition provided no incentive to keep costs down.

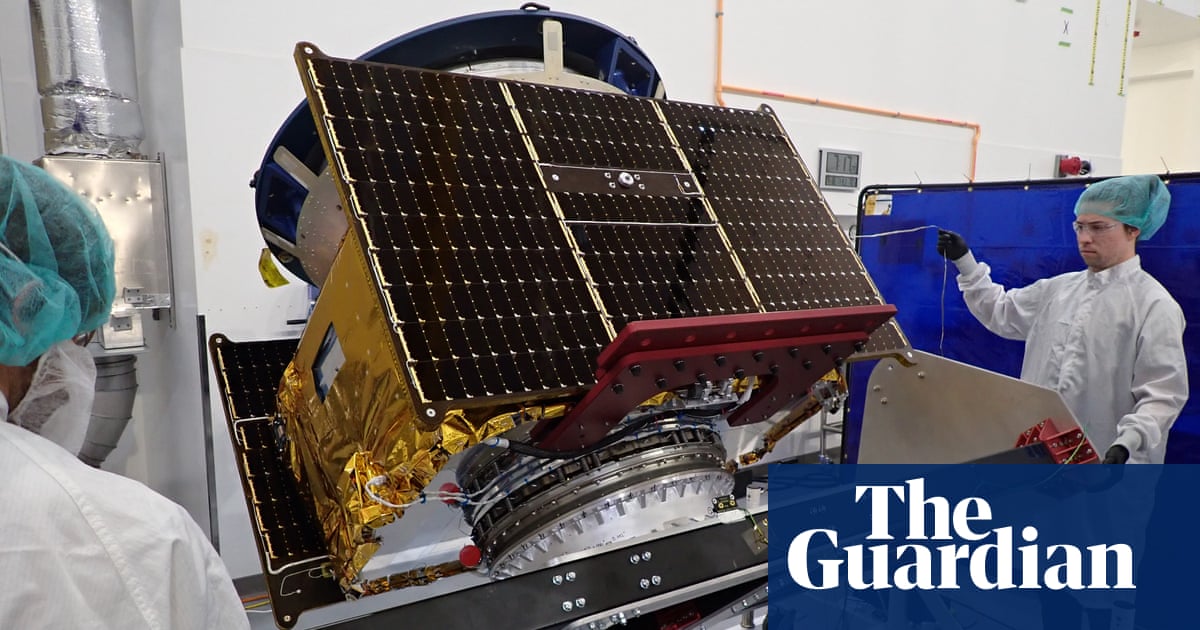

Now that is changing. Apart from the involvement of Musk’s SpaceX company, the aerospace giant Boeing has also built its own spaceship, Starliner, and later this year it also plans to ferry astronauts to the space station. On the sidelines, companies such as Blue Origin, founded by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, Virgin Orbit, founded by Richard Branson, and several other companies are also working on their own commercial space plans.

“That should slowly have an effect,” said De Winne. “Space travel should become cheaper as these different companies compete, and that will mean we can spend more on our satellites and probes and less on launching costs.”

It has not been an easy task, however. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launcher – which will ferry Crew Dragon into space – broke apart once in flight and once during a ground test. Boeing suffered numerous software failures during test missions of its Starliner, and only flew in space, uncrewed, last December. Commercial launches were planned for 2017 but are only now set to take place.

Falcon 9 and Crew Dragon are now standing at Kennedy’s launch pad 39A and should lift off for the space station on Wednesday. Should the mission be scrapped at the last minute, however, Boeing’s Starliner spaceship will then have the chance to become the first manned commercial spaceship.

And thereby hangs a tale. Starliner will be commanded by Charles Ferguson, who was commander of Atlantis on its last mission, and who was involved in leaving the flag and message on the space station hatch.

Intriguingly, on that mission he was accompanied by Doug Hurley, who is now the commander of Crew Dragon. Both men have remained in the US manned space programme and are rivals to bring back the flag, with Hurley in pole position. Ferguson remains unflustered. “Regardless of who might get there first, it’s a win for America,” he says.