n the middle of a global pandemic, which has to be squeezed down in every country to prevent it returning in wave after wave, Boris Johnson has announced that he will close the Department for International Development (DfiD). He called it a merger but made it absolutely clear that the foreign secretary would be in charge.

Prior to 1997, the UK’s development work – which means working to alleviate systemic problems such as poverty and disease across the world – was part of the Foreign Office and it faced constant battles to prevent arm sales or trade deals distorting the spending of development assistance. In the case of the Pergau Dam scandal in 1994, hundreds of millions of pounds in aid money was linked to an arms deal in Malaysia. There was a constant battle for the development people to try to block arms or trade deals that would throw poor countries into debt they couldn’t afford or make them sign up to contracts that would bring little benefit to the people. The development perspective lost out frequently because the foreign secretary had the final say and they saw their duty as the promotion of short-term political and commercial interests. The UK also has an interest in a just and stable world order, but that takes a longer-term view.

In 1997, DfiD was established as a full government department headed by a cabinet minister; I was the first to take up the post. This meant more than attendance at cabinet. It meant that in all cross-Whitehall work, the development perspective was brought to the fore. In the end decisions have to be made and, even with DfiD in existence, sometimes commercial considerations won out. Notoriously, Tony Blair overruled myself and DfiD and insisted that a highly questionable air traffic control deal for Tanzania should go ahead. It later went to court in the US over corruption claims, and nearly £30m had to be repaid. But if DfiD had not existed, the argument would not have even made it to the top of the government as it would have been ruled on by the foreign secretary.

The UK did not have a reputation for effectiveness in development before the establishment of DfiD. It was as that reputation grew that successive governments took pride in it and expanded the budget. Britain is now seen as one of the leading development players in the international system. Of course, the right wing have always hated it; that “taxpayers’ money was being spent on foreigners” became a familiar trope in the rightwing press. Now Johnson is trying to play to that base.

In his statement to the House of Commons, Johnson stressed two reasons for his decision to abolish DfiD. Firstly, aid should be spent on UK interests – for example, less should be spent in Tanzania and Zambia and more in Ukraine and the Balkans. But later he said that scandals such as Pergau would not happen again because we have the International Development Act. I’m proud of having drawn up and introduced that act. It lays down that the sole legal basis for British aid spending is the reduction of poverty. It would therefore be illegal for Johnson to withdraw aid from Tanzania and Zambia to give to Ukraine and the Balkans because of his concern about Russian power.

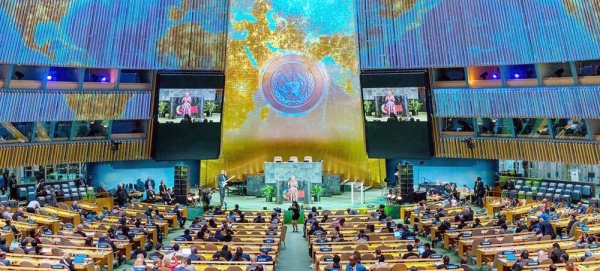

The second reason, which he repeated over and over again, was that the foreign secretary and ambassadors had to be in charge of decisions. Maybe in some strange way he was trying to find an excuse for his widely agreed poor performance as foreign secretary. But this demonstrates that he does not understand how development works. Half of UK spending is dispersed through the multilateral system – the World Bank, the IMF, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and the UN. There are no ambassadors involved in policy decisions in these institutions.

On the World Bank and IMF, DfiD works with the Treasury. On trade policy and the WTO, it works to influence the Department of Trade as well as the WTO itself. In the UN, our humanitarian experts work with the UN’s system and put in money and resources where there are gaps. On health, DfiD experts help the Department of Health to understand global issues. On conflict resolution, DfiD works with the Ministry of Defence, as we did intensively in Sierra Leone and Kosovo. Getting rebels disarmed and resettled, and helping people displaced by conflict to return home and reestablish their livelihoods requires expertise that ambassadors and foreign secretaries lack.

DfiD also employs experts from around the world in health, economic development and social development, engineers focused on climate change and water and sanitation systems, and urban planners who understands the challenges of growing slums. The mix of skills is enormous and the job of DfiD is to use this expertise to improve our bilateral programmes in the poorest countries and to improve the working of the international development system. In all cases, there is full consultation with the Foreign Office on our strategies for each country, and full cooperation with high commissioners and ambassadors in countries where we have programmes.

It is remarkable that at a time when the pandemic must be halted everywhere, and when the global economic downturn is going to throw hundreds of millions into poverty, Johnson is abolishing the authority of DfiD. And, just as the Black Lives Matter campaign has drawn attention to the UK’s history of slave trading and colonial plunder, the government’s capacity to work on a basis of partnership with the countries that still suffer some of the effects of that history is to be severely undermined. The prime minister thought it funny to call the UK aid budget a “cash point in the sky”. For a few short-term political gains, the reputation and influence of this country is going to deteriorate accordingly.

• Clare Short was Labour secretary of state for the Department for International Development from 1997-2003