ou’d think that if you found the first evidence that a planet larger than the Earth was lurking unseen in the furthest reaches of our solar system, it would be a big moment. It would make you one of only a small handful of people in all of history to have discovered such a thing.

But for astronomer Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington DC, it was a much quieter affair. “It wasn’t like there was a eureka moment,” he says. “The evidence just built up slowly.”

He’s a master of understatement. Ever since he and his collaborator Chad Trujillo of Northern Arizona University, first published their suspicions about the unseen planet in 2014, the evidence has only continued to grow. Yet when asked how convinced he is that the new world, which he calls Planet X (though many other astronomers call it Planet 9), is really out there, Sheppard will only say: “I think it’s more likely than unlikely to exist.”

As for the rest of the astronomical community, in most quarters there is a palpable excitement about finding this world. Much of this excitement centres on the opening of a giant new survey telescope named after Vera C Rubin, the astronomer who, in the 1970s, discovered some of the first evidence for dark matter.

Scheduled to begin its full survey of the sky in 2022, the Rubin observatory could find the planet outright or provide the clinching circumstantial evidence that it’s there.

Discovery of the planet would be a triumph, but also a disaster for existing theory about how the solar system was created.

“It would change everything we thought we knew about planet formation,” says Sheppard, in another characteristic understatement. In truth, no one has a clue how such a large planet could form that far from the sun.

The distant solar system is a place of darkness and mystery. It encompasses an enormous volume of space that begins at the orbit of Neptune, some 30 times further from the sun than Earth, or 30 astronomical units (AU)the , and extends to about 100,000AU. That’s almost one-third of the distance from the sun to the next nearest star.

It was in the inner regions of this volume that American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto in 1930. Although Pluto possessed just two-thirds of the diameter of our moon, it was originally classed as a planet.

By the end of the century, however, telescopes were bigger and astronomers were beginning to find more tiny worlds beyond Neptune. They were all even smaller than Pluto until 2005, when Mike Brown from the California Institute of Technology discovered Eris. It was at least the same size as Pluto and probably bigger, so, if Pluto was a planet, so was Eris. Nasa hastily organised a press conference and announced the discovery of Planet 10.

About a year later, the International Astronomical Union ruled that Pluto and Eris were effectively too small to be called planets and renamed them dwarf planets. So the solar system’s roll-call returned to eight: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune. And a cottage industry of finding distant solar system objects really got going.

The path towards Planet 9 began one night in 2012, when Sheppard and Trujillo were using the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory’s telescope in Chile. They were finding more and more distant objects, but one in particular stood out. Catalogued as 2012 VP113, they nicknamed it Biden after the US vice-president at the time (because of the letters VP in the catalogue designation). To their amazement, this far-flung world never came closer to the sun than about 80AU. At its furthest, Biden would reach 440AU into deep space, meaning that it followed a highly elliptical orbit. But that wasn’t the most remarkable thing about it.

By some weird coincidence, its orbit appeared to be very similar to that of another distant world known as Sedna. This mini-world had been discovered in 2003 by Brown, Trujillo and David Rabinowitz of Yale University. It immediately stood out because of its highly elliptical orbit, which swings from 76AU to 937AU.

“Objects like Sedna and 2012 VP113 can’t form on these eccentric orbits,” says Sheppard. Instead, computer simulations suggest that they form much closer and are then ejected by gravitational interactions with the larger planets. The truly odd thing, however, was that the two elongated orbits pointed in roughly the same direction.

And the more Sheppard and Trujillo examined the other objects in their catch, the more they saw that those orbits were aligned, too. It was as if something was corralling those tiny worlds, like a sheepdog manoeuvring its flock. And the only thing they could think of that was capable of doing that was a much larger planet.

Curiosity piqued, they did some calculations and discovered that the planet their results were hinting at had to be somewhere between two and 15 times more massive than Earth, on an orbit that lies on average somewhere between 250AU and 1500AU from the sun. Their results were published by the prestigious journal Nature in March 2014 and interest in Planet 9 began to sweep the astronomical world.

The next big leap came in 2015 when Sheppard and Trujillo were among the scientists who discovered 2015 TG387. They nicknamed this one the Goblin. It’s the third most extreme object behind Sedna and Biden and it, too, lines up, reducing still further the idea that this alignment is a random coincidence.

In 2016, Brown and his collaborator Konstantin Batygin, also of Caltech, published their own analysis of the data. Agreeing with Sheppard and Trujillo about the size and distance of the planet, they even suggested an area of sky where they thought it might be found.

But not everyone is convinced.

Pedro H Bernardinelli, a PhD candidate at the University of Pennsylvania, realised that Sheppard’s data wasn’t the only place one could look for distant worldlets. So he turned to some initial data from a cosmological survey that was designed to measure the way in which the universe is expanding by looking at far-away galaxies. He searched the data for the celestial equivalent of a photobomb, looking for distant solar system objects that just happened to get in the way of the camera. He found seven.

At first sight, it looked as if these worldlets were also aligned as expected, but the more rigorously Bernardinelli analysed the data, the weaker he felt the alignment became. “We don’t think we see the signal in our data,” says Bernardinelli, although he admits the he can’t yet definitely rule out the planet and has yet to run the analysis on the full survey data. “Our answer might change the next time we do this,” he says.

These days, Sheppard can regularly be found using Japan’s Subaru telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, patiently scouring the sky for more evidence of Planet 9, maybe even hoping that he sees the planet itself. The scale of the task is enormous. It really is like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack. The planet – if it is even there – is very faint and the sky is very large. But help is on its way in the form of the Rubin observatory.

Rubin is a monster that will devour the sky. Whereas most telescopes would take months or years to survey the whole sky, Rubin will do it in just three nights. Then do it again and again and again to see what’s changed and so catch the moving objects.

Construction is nearing completion, and the telescope is set to open its giant eye for the first time later this year. Commissioning and tweaking will then take another couple of years.

“That survey is going to change solar system science as we know it,” says Sheppard. And if Planet 9 is out there, Rubin should see it.

“We can detect an Earth-mass planet at around 1000 AU,” says Meg Schwamb, of Queen’s University Belfast, who co-chairs the Rubin observatory’s solar system science collaboration. That puts Sheppard’s world easily within its sights. “If others haven’t seen Planet 9 before our survey starts then, I think, all eyes are on the Rubin observatory,” says Schwamb.

Even if the telescope fails to see the planet directly, it will detect many more distant mini-worlds that can all be use to triangulate the planet’s position more precisely, thus helping to narrow the search area. And if Planet 9 really is out there, then the consequences will be huge.

Astronomers think that the solar system formed in a disc of matter surrounding the sun. That matter condensed into smaller bodies, which then collided to form larger ones. At the end of this process, the planets were born. But the matter in this disc thins out further from the sun, meaning there is not enough raw material to form a large planet in the distant solar system.

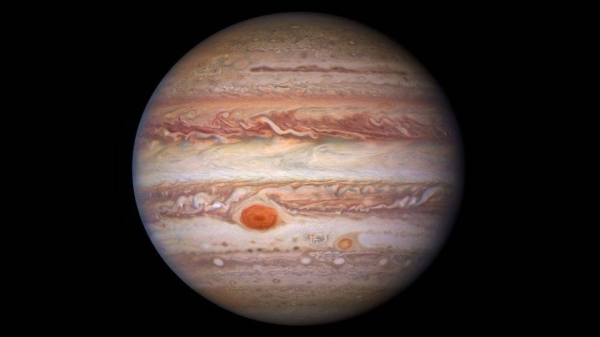

To rescue the standard theory, some suggest that Planet 9 was once destined to become a gas giant like Jupiter or Saturn and so was forming alongside them. However, a gravitational interaction stunted its growth by hurling it out into the dark.

But Jakub Scholtz of Durham University is sceptical. “It’s possible,” he says, “but it actually requires quite a lot of coincidences.” That’s because a single gravitational interaction can’t do the job. Instead, a series of interactions is needed to place it in an orbit that never brings it back to where it formed.

Scholtz has a more exotic idea. Together with collaborator James Unwin, of the University of Illinois at Chicago, he has suggested that the object corralling these distant worldlets is not a long-lost planet but a black hole.

If so, not even Rubin will be able to see it, because black holes emit no light whatsoever – they simply swallow light and anything else that happens to cross their path. It is a tantalising possibility because Scholtz’s black hole would have to be part of a long-suspected but never-proved population of black holes that were formed shortly after the formation of the universe.

But for the time being, most other astronomers seem more than content with the idea that there’s a large planet out there in the darkness, just waiting to come into view in the next few years.

And if Planet 9 really is there, then perhaps the first time Sheppard sees it through a telescope, he will finally experience something akin to a eureka moment.