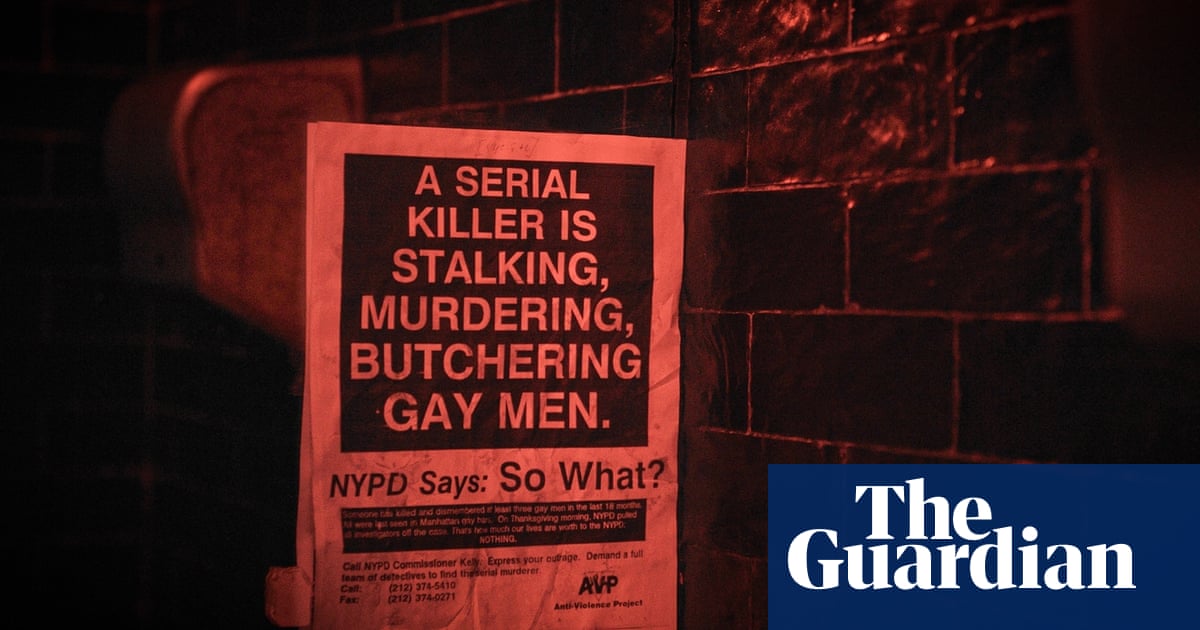

s a legal term, “outcry” refers to the first admission by a victim of sexual assault, the testimony which launches a police investigation, a process more familiar to most Americans through television procedurals such as Law & Order: SVU than personal experience. On the big and small screen, this would seem to be a straightforward process, especially if the person making the outcry is a child – log it, believe it, investigate, catch, prosecute. So it would seem in July 2013, when a four-year-old boy told his parents, who then informed police in Williamson county, a tony suburb north of Austin, Texas, of sexual assault by a high schooler he named as Greg.

Greg Kelley, then a 17-year-old rising senior and star of the Leander high school football team, was promptly arrested.

It seemed like a clearcut case – Kelley was living with a friend’s family to maintain residency in the district, at a house which also hosted the in-home daycare center attended by a four-year-old. Soon, police reported another outcry by another four-year-old daycare attendee. Kelley maintained his innocence but was convicted in 2014, aged 18, of two counts of aggravated sexual assault of a child, and sentenced to 25 years in prison without possibility of parole.

But as documented in Showtime’s five-part series Outcry, the case was hardly an open-and-shut deal. Following his conviction, hundreds of people, particularly fellow high schoolers, in Leander and neighboring Cedar Park rallied around Kelley’s innocence – not the response you’d necessarily expect for someone accused of sexually assaulting small children, no matter how high their profile in the quasi-religion that is Texas high school football.

A counter-group rallied around the cause of believing testimonies of sexual assault. Believe the children versus believe the man proclaiming innocence and a railroaded conviction. As Outcry reveals, however, the case was far more twisted than a polarized small town; over the course of five episodes and three years of filming, the Greg Kelley story unfolds in real time – with some participants experiencing major twists and shocking news on camera – to reveal a surprising, thorny, hyper-local yet deeply concerning saga of prosecutorial misconduct and a botched investigation, a confusing conviction process and the misunderstood psychology of child confessions.

Outcry’s director, Pat Kondelis, lives in Williamson county, but didn’t hear about the Kelley case until a friend suggested he look into it while premiering another project, Disgraced, at South by Southwest in 2017. At first, “I initially wasn’t excited about doing it,” he told the Guardian. “There was so much information that people were giving me, and I didn’t know what I could believe, what I should believe. It was very different, from a developmental process, than anything else that we’ve done.”

He met with Kelley’s family, by then desperate for an outside look into the case. By the time Kondelis began filming in 2017, Kelley had spent three years in prison and “we had no idea where this story was going to go”, said Kondelis.

He did, however, know the law enforcement reputation of Williamson county, an area notorious for its unforgiving application of the law (the county drew national attention in 2014 for charging a 19-year-old who made pot brownies with felony charges that threatened life in prison) and high-profile cases of miscarried justice (such as Michael Morrison, who served 25 years in prison for a murder he did not commit after Williamson’s prosecution withheld evidence. He was released and exonerated in 2013). At the time of Kelley’s arrest, the “throw-the-book-at-people” attitude was something Williamson county law enforcement wore “as a badge of honor – you don’t do it here. And if you do, you’re going to pay,” said Kondelis.

By the start of the series, however, a changeover in county officials allowed Kondelis, the new district attorney, Shawn Dick, and Kelley’s replacement lawyer Keith Hampton to look into the case and a potential appeal. “Every interaction I had with Williamson county in the three years of making this was a positive one,” Kondelis said. “They were open and transparent, and that’s not what I was expecting.” Without spoiling too much – the series unfolds as the film-makers experienced it, which according to Kondelis was “a rollercoaster … one day you feel pretty strongly you know what happened, and then the next day something happens and it totally changes your mind” – the re-examination of Kelley’s conviction revealed startling incompetence, misconduct and general misunderstanding on the veracity and techniques of child trauma interviews.

The officer tasked with investigating the four-year-old’s outcry never even visited the scene of the alleged crime. Kelley’s attorney, hired at the suggestion of the owner of the daycare center, was revealed to have troubling conflicts of interest. A potential alternative suspect went entirely un-investigated, among other disturbing revelations about the county’s handling of the case. Prosecutors changed alleged timelines to meet alleged narratives.

“It was a constant back and forth,” said Kondelis of the filming experience over three years. “You have to be open-minded and consider all possibilities, because you don’t know all the information yet.”

All the while, the case garnered significant and sustained local media attention, especially after Kelley was released on bond in 2017 pending the reopened case, and exacerbated by his status as a local football star – few things grab America’s attention like the story of thwarted athletic potential on behalf of young men. Outcry also explores both sides of fervent support in the case – on behalf of the “Pray for GK” group who believed (some based on personal connection, some based on popularity) in Kelley’s innocence, most especially his mother, Rosa, and girlfriend, Gaebri Anderson; and the victims’ rights advocates who understood that one discredited sexual assault claim could threaten the seriousness afforded all others.

“You had camps on both sides that were completely dug in and both believed that they were fighting a righteous fight,” Kondelis said. “Each side digging their heels in in their belief that they were protecting the innocent.”

Still, he noted, the specifics of Leander, of Williamson county, and of Texas football, warped the visibility of the case. “If Greg had not been the star high school football player from Leander high school, he wouldn’t have gotten as much support as he did,” Kondelis said. “If this also didn’t happen in Williamson, where there’s a long, storied history of wrongful conviction, he wouldn’t have gotten the support that he did.”

Ultimately, the critical and nuanced re-examination of Kelley’s case, as well as evidence-based reappraisal of child outcry interviews – the high instances of suggestibility, the ease with which investigators can induce a false memory or fabricated confession – led to resolved justice for Kelley (the case’s resolution is public information, but no spoilers here). Though the case, as any, is specific and messy in its particulars, “there’s a lot to be learned there,” said Kondelis, “and I hope [people can] get a greater sense of how these investigations and these prosecutions actually work, because they’re far different from what we’ve been programmed to see in television and film.” You assume competency; you assume easily delineated narratives.

“Most Americans believe if a serious crime were to happen to a member of their family, that the prosecutors and the police are going to drop everything and attack a case like that as if it were a member of their own family,” said Kondelis. “That is absolutely not how it works.

“It’s certainly not what happened in this case.”

Outcry is available on Showtime in the US every Sunday and in the UK at a later date