Mini-African summit fixed for Tuesday in the latest effort to break protracted deadlock

Experts say disagreements run deeper than technical matters and the sharing of water

DUBAI: When Egyptian, Ethiopian and Sudanese officials meet to resolve their differences on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) that Addis Ababa is building on the Blue Nile, they instantly run into many thorny issues.

These disputes run deeper than technical matters and the sharing of water, experts and analysts say. Because they are also legal, historical and trust-related, a tripartite agreement has proved elusive. An eventual deal could take longer because major differences persist, mainly between Ethiopia and Egypt.

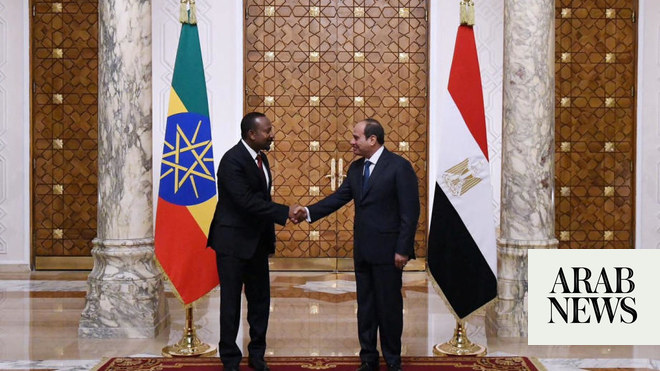

Officials from the three countries concluded two weeks of talks on July 13, supervised by the African Union (AU) and observed by US and European officials, but came no closer to an agreement. Officials were quoted as saying that the three countries would submit their final reports to the AU and that a mini-African summit would be held on Tuesday.

The talks were the latest in a decade-long effort by the three African countries to resolve differences over the GERD. Ethiopia hopes the 6,000-megawatt dam will turn it into Africa’s top hydropower supplier. Egypt and Sudan fear the dam — being constructed less than 20 km from Ethiopia’s eastern border with Sudan — will substantially reduce their water share and affect development prospects.

While Addis Ababa insists the dam will benefit all Nile river basin states, the three countries are stymied by technical issues on how and when to fill the reservoir and how much water it should release, along with procedures for drought mitigation.

Experts and analysts from Africa and outside say the differences are fundamental and require sincerity. “Vital national interests are at stake, particularly on the Egyptian and Ethiopian sides,” said William Davison, a senior analyst on Ethiopian affairs with the Brussels-based International Crisis Group.

Ethiopia considers the project important for development and thus named it the “renaissance dam,” he said, adding: “It is also seen as vital to overcoming injustices from past treaties that excluded the country and denied it water allocations.”

Egypt, which relies heavily on the Nile for agriculture, industry and drinking water, worries that such a large dam will reduce water supplies “in a problematic way” in the future, Davison told Arab News from Addis Ababa.

Satellite images released recently showed water pouring into the reservoir, prompting Seleshi Bekele, the Ethiopian water minister, to assuage Egyptian anxieties by insisting that the process was the product of natural seasonal flooding and not direct action by the government.

Egyptian analysts say Ethiopia is ignoring its neighbors’ interests. “The talks have failed because of continuous Ethiopian obstinacy,” said Hani Raslan, an expert on African affairs at the Cairo-based Al-Ahram Center for Strategic and Political Studies. “Ethiopia has been buying time to impose a new reality on the ground . . . they don’t intend to reach an agreement.”

Other experts say that a positive attitude by the parties would help. “There is a tendency on each side to see the other in a more threatening manner, which I think is the key issue here,” said Mulugetta Ketema, managing director of the US-based Cogent International Solutions, a research and analysis center.

“Instead of starting negotiations based on who can dominate over which country or region, I think you should start by saying ‘How can we work together to utilize his river.’”

Ketema, who is Ethiopian-American, added: “I am sure everybody is doing their best, but there is a historical issue also at play here. For centuries Egypt and Sudan didn’t have anybody saying they could do this or that . . . they have been using the river for their own advantage.

“However, now the basin countries . . . are also growing and saying ‘Hey, we have to use or share something with our brothers and sisters up north and harvest the river.’ Apparently, this is where the problem starts.”

The Nile basin includes Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan, Congo, Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan and Sudan. Most were not part of the agreements signed during the British colonial years that gave Egypt and Sudan a big share of the Nile waters, Ketema said. Except for Ethiopia, those countries were under British control.

Apart from the legal differences over the term of references consultants use in their reports, drought mitigation remains a major obstacle. Egypt and Sudan seek Ethiopia’s commitment to a safe minimum release of water in dry seasons. Addis Ababa has been unwilling to do so, according to Davison.

“More recently, in the negotiations, there has been a series of legal disputes or disagreements. Sudan and Egypt would like a process of binding third-party arbitration as a last resort to resolve any future dispute (but) the Ethiopians . . . are not willing to sign up to that,” he told Arab News.

Ethiopia insists that Africa needs to solve African affairs. “Historically, Africans have been solving their own problems and did a better job than outside interference,” Ketema said. “Europeans and the UN tried to mediate in some issues, but it really never worked.” Should the AU fail to reach a solution on the GERD, other developing nations could extend their hands, he said.

To many Egyptian analysts, Ethiopia’s insistence on “African solutions” aims to “keep the negotiations going in a vicious circle until the dam is completely full and then there will be no meaning for negotiations,” Al-Ahram Center’s Raslan told Arab News.

“A practical solution is available already,” he said, referring to a US-drafted agreement that emerged from talks in Washington DC earlier this year. Egypt initialled the document, while Ethiopia declined.

The ministers agreed on a schedule for a staggered filling of the dam and mitigation mechanism, according to the document, but still needed to finalize details on safety and ways of handling future disputes. Praising Egypt’s readiness to sign the agreement, the US noted that Ethiopia sought internal consultations.

Davison said that the parties need to focus on specific disagreements on hydrological and legal issues “without being sidetracked by the current controversy over the act of filling (water) and . . . by the historical and geopolitical disagreements.”

“If the lawyers and engineers are allowed the space to reach a compromise on these technical issues, that will not solve everything,” he said.

“But that will allow some sort of agreement (so that) the parties can move on and build trust. Eventually, they will be able to address some of the large issues over water sharing and ultimately this historical rivalry over the river.”