hen Rishi Sunak appeared in a press conference in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, he used three words to convey to the public his commitment to steer the UK through the crisis: “whatever it takes”. It was a phrase that immediately won him plaudits from both Conservative supporters and those on the left, for whom Boris Johnson’s demeanour has often proved a turn-off. The £350bn package that he announced alongside it – from business loans to the furlough scheme – also helped.

But it’s one that has since come back to haunt the man who has become the most popular politician in the country. With the deficit for the financial year forecast at more than £300bn, he and his team have found it difficult to turn the taps off. There have been a string of government U-turns owing to parliamentary pressure on issues from the NHS surcharge to free school meals. Each time, the recurring line has been that the paltry sum of a few million is nothing in the grand scheme of things. And after all, the chancellor said he would help. “The focus should be on the billions not the millions,” says one MP.

With the furlough scheme being wound down from next month and a hard winter ahead, things are about to get even more challenging. Not only does Sunak need to come up with a plan to guide the UK out of the economic crisis and on to steady ground, he needs to be able to sell it to the new coalition of Tory MPs in traditional Conservative seats and those in the red wall of former Labour heartlands.

When the chancellor says the UK is moving into the “second phase” of its response to the crisis, he is attempting to draw a line under four months in which the economy has in effect been put on life support. While it’s still the case that the Treasury is prepared to pile resources into securing PPE and health provisions as required, it is no longer willing to pay the wages of a quarter of the UK workforce. “It’s non-negotiable that the furlough scheme needs to end,” explains a government figure.

With the UK’s debt now worth more than its economy for the first time since 1963, it’s not clear that Sunak could keep emergency measures in place indefinitely even if he wanted to. While this government is comparatively relaxed about borrowing compared with the Cameron/Osborne era, there is an acknowledgement that a plan needs to be in place to return to a normal level of borrowing. Speaking earlier this month, Sunak appeared to throw the few remaining fiscal hawks a bone when he said he would need to come up with a plan to balance the books over the “medium term”.

There have been hints of late about what is to come. On the day of the Russia report, the chancellor announced plans for the government’s comprehensive spending review – warning of the need for public sector pay restraint and telling departments to find savings. This is in the buildup to Sunak’s autumn budget, which is viewed as the first step in setting out a path to balancing the books. While this won’t be a primarily revenue raising budget, tax rises cannot be ruled out – each week reports of mooted ones emerge in the papers.

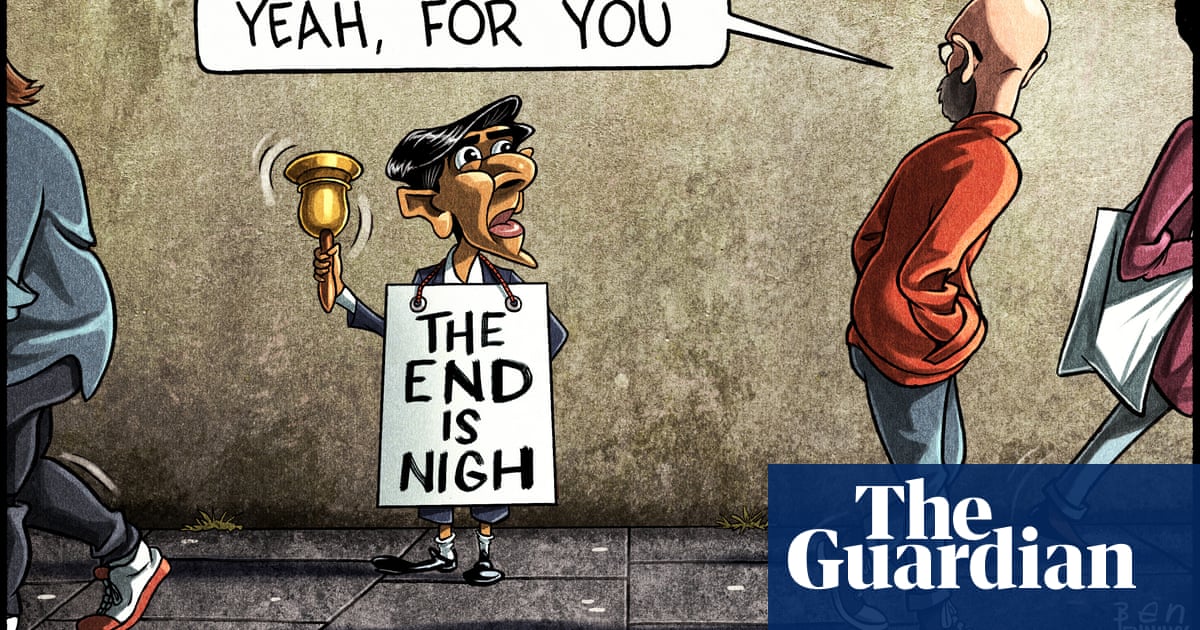

But after an extraordinary few months, how does the government break the news that the new “new normal” involves a lot less money? As Conservative MPs look to a winter of local lockdowns and little relief, there remains a sense that the government must move to support Britons struggling through no fault of their own. “Boris keeps saying austerity is over,” explains a Tory MP. “The problem is everyone starts to think there is endless money – and the past few months have done little to suggest otherwise.”

As well as talking down disgruntled MPs with new spending requests, a conversation must begin on balancing the books regarding what has already been spent. This will prove the hardest. “There’s a disconnect between money spent and how it’s to be paid for among the MPs,” says a government figure. The concern is that even those MPs who are not currently pressurising the Treasury for funds have yet to realise that the huge sums borrowed so far have consequences for the government’s spending plans.

While there are a handful of fiscal conservatives in the party – including the likes of John Redwood – the bulk of Tory MPs have grown to be rather relaxed about borrowing. They view a return to mass cuts as politically toxic and don’t want to go near it. The One Nation Conservative group, which includes MPs such as Damian Green and Victoria Atkins, has gone so far as to organise Zoom calls on how to avoid any austerity.

While No 10 is opposed to big spending cuts, other measures could be on the table. Johnson’s first instinct is to go for growth but even these measures have so far proved controversial. A plan to temporarily relax Sunday trading laws to stimulate the economy was pulled when the old Christian right of the Tory party began to rally MPs to their cause.

Some form of tax rise is viewed as likely – with an online sales tax the latest to be under discussion. This immediately divided opinion with Telford MP Lucy Allan voicing her opposition after West Midlands mayor Andy Street suggested it was a good idea. But Johnson has said recently that the government will not raise income tax, national insurance or VAT for five years and will protect the state pension triple lock.

This is where it all becomes rather dicey. The new Tory coalition all have different views on who should carry the burden. In the 2019 election, the Conservatives made huge gains in Labour heartlands – winning some seats for the first time. These MPs have been deemed thin-skinned by colleagues for taking to WhatsApp regularly to raise grievances. When I asked one whether they would support tax rises in the wake of coronavirus, they replied: “Tax rises were not in the manifesto.”

“They are against anything that punishes their voters,” explains an MP from the older intake. “The cost of living is crucial to these MPs so issues like car parking in hospitals and fuel duty are potentially toxic.”

The One Nation Tories share the view that the burden ought not to fall on the poorer in society, or the young. “They are the group most likely to support a tax rise so long as it was part of a moral argument on higher earners,” says a colleague.

But shire Tory MPs, or those in traditional Tory seats, take a different view. They worry that core supporters are being passed over in favour of would-be Tory voters or ones that can’t be relied on at the next election. In their eyes, the burden should not be on affluent older voters – particularly not the self-employed.

If Sunak cannot find a path back to economic health through growth, the popular chancellor is going to soon be unpopular on one side of his party.

Katy Balls is the Spectator’s deputy political editor.