y father was let go this month by the institution to which he had devoted 41 years of his life. There to greet him, past the sliding glass doors of the American University of Beirut Medical Centre (AUBMC), stood Lebanese soldiers, guns in hand, and the sagging figures of his erstwhile co-workers, 850 of whom had suffered a similar fate.

It is fitting that as I write this I am guided only by the light from my screen and a candle, which I have placed not far from my feet. Power outages have long been a constant in Lebanon. The most severe economic crisis since the country’s independence, and the resulting fuel shortage, has meant that private generators have struggled to keep up with the additional burden.

How did we get here? Decades of chronic mismanagement and rampant corruption by the sectarian ruling class since the end of the civil war (which ran from 1975 to 1990), coupled with the central bank’s acrobatic feats of “financial engineering”, have plunged the country into darkness. Nearly half the population now find themselves officially below the poverty line, their salaries, savings and retirement funds reduced to a pittance, with the lira having lost more than 70% of its value against the dollar. Lebanon has the distinct honour of being the first country in the Middle East and North Africa region to experience hyperinflation.

Lebanese banks had been lending depositors’ dollars to the heavily indebted state while offering impossibly high interest rates to the depositors themselves. Reuters has reported that the central bank inflated its assets by more than $6bn in order to artificially prop up the country’s economy. It may soon became unable to service the public debt of more than $86bn or pay back the annual interest to the local banks.

The resulting devaluation of the lira and the rapid price rise in goods and services has led to an equally sharp increase in suicide rates, hunger-crimes and plain hunger. Just a fortnight ago, prior to my father’s dismissal, my hitherto middle-class family and I had a serious discussion about whether or not meat was necessary moving forward. Last month, a man shot himself outside a Dunkin’ Donuts on Hamra, a popular high street in Beirut. He left a note that read: “I am not blasphemous …”: a line from a Ziad Rahbani wartime song ending with “but hunger is blasphemous”.

I do not know for certain what must have gone through my father’s mind as he walked out of the AUBMC for the last time, but I suspect that he would have emerged with a knowing smile. Economic woes and young men with guns must have seemed all too familiar to the man who spent the Lebanese civil war running back and forth between his flat and the AUBMC, working night shifts as a cashier while the shrapnel and the bullets descended around him. Through the war-torn 80s, and in the darkest hours of the power-deprived Beirut night, my father would look to the luminescent eyes of a black cat for light. It often ambled alongside him when the shelling intensified, and would disappear thereafter, frequently returning when another long walk to the night shift beckoned. In a way, I suspect that the presence of armed men, called in pre-emptively by the university, citing “credible external threats”, was a more suitable farewell than a gold watch.

It was my parents’ shared dream that my sister and I would one day lecture at the university, like those many professors and doctors whom my father had observed dashing in and out of their lecture halls – those whose offices he had intermittently frequented when curiosity overwhelmed him or the walls of academia parted to reveal to him the erudite, the learned, in whom he placed his faith in a better Lebanon.

But there is no point in pretending that his time at the country’s most prestigious institution and largest non-state employer was anything more than a marriage of convenience. My father’s ambition was not to be a cashier. It was to be a poet, and then when his youth had deserted him, a critic (which he did sparingly). There were good times. My own education would not have been financially possible – given the AUB’s high tuition fees – were it not for his employment by the university itself, which waived the cost. At my graduation ceremony, my father proclaimed that it was all worth it, and then went back to his evening shift.

When I heard the news, I cracked open an old bottle of wine and we toasted his career. I also, unthinkingly, passed him my phone with a clip of his former colleagues on social media: a young nurse who was the only source of income for her bed-ridden mother, a 64-year-old man who was helped off his office chair in the midst of his shift and told to go home, a cancer-stricken middle-aged man whose sacking was essentially a death sentence – and who never once requested sick or compassionate leave.

My father stole a sharp, Arctic intake of breath, which did not seem to come from that thick, heavy Beirut summer air. I believe that he saw what could have been, how much worse it might have turned out for him, for me, for our entire family, had he not been fortunate to hang on to his job for as long as he had, had he not willed himself through those dark walks in the heat of the civil war. He pitied the nation, the youth, the next few cumbersome steps that he would now sit out. My mother, who had in fact led the toast, placed a hand on my shoulder and informed me that I would never forget this moment for as long as I live. She still remembered when her father was unceremoniously dismissed from his job.

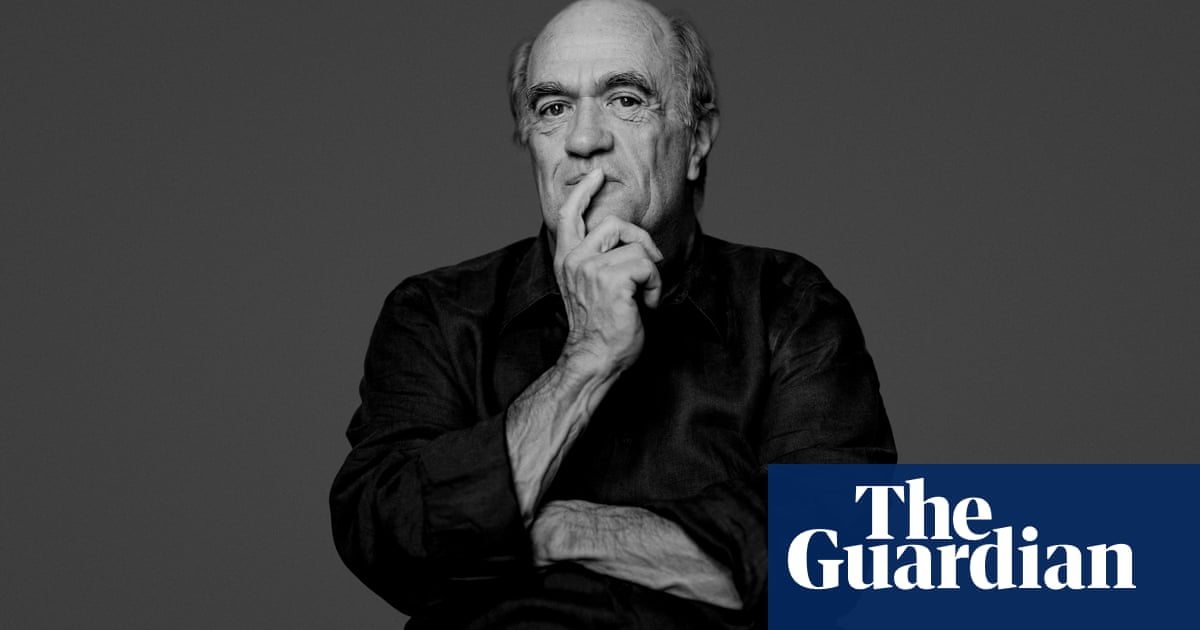

• Naji Bakhti is a Lebanese author whose novel Between Beirut and the Moon will be published in August by Influx Press