It was hoped at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic that the economic fallout wouldn’t last too long. But as summer hurtles towards autumn, the catastrophic scale and persistence of the crisis is becoming increasingly clear.

Germany extending its furlough wage subsidy scheme from 12 to 24 months is a decision being taken against this backdrop. The longer the economic damage lasts, the more help Berlin estimates its economy will require to weather the storm. Unemployment around the world is climbing, with a steady drumbeat of job cuts announced by big-name companies with every passing week.

The latest bad jobs news in the UK has been Marks & Spencer axing 7,000 staff, hot on the heels of other big high street names such as John Lewis, Boots and Debenhams. Unemployment is expected to more than double to 1980s levels by the end of this year.

Vast job losses have been announced in Germany, too, including in its powerhouse car manufacturing industry and at the national airline, Lufthansa. But the jobless rate is not expected to rise as much as in Britain, partly because of its short-time working scheme (Kurzarbeit).

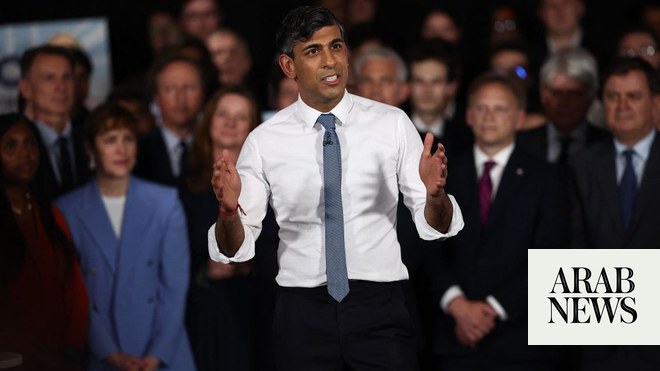

Despite mounting warnings over the scale of the jobs crisis, Rishi Sunak, the chancellor, has ruled out following Germany’s example, which economists believe could save millions of jobs.

At the start of August, up to 4.5 million people in Britain remained furloughed, according to the Resolution Foundation. A total of 9.6 million people have benefited from the scheme since its launch in March, at 1.2m companies, at a cost of £34.7bn to the exchequer so far.

But given the scale of the pandemic, risks from a second wave in infections, and continued weak demand for goods and services in the hardest-hit sectors of the economy – such as retail, travel and hospitality – significant numbers of workers are still expected to be on the scheme when it ends. According to the IPPR thinktank, these factors could result in the loss of 2m viable jobs.

In Germany, Kurzarbeit is currently supporting 5.6m jobs, down from a peak of 7.3m in May. At the outset, Berlin expected it would cost €10bn (£9bn) to provide 12 months of support. It believes an extension of 12 months – taking the scheme well into 2022 – would cost roughly the same again.

Part of the difference in cost is the structure of the scheme. In the UK, the state paid 80% of wages while workers were forced to stay at home at the height of the scheme. It will reduce the level of support and allow part-time work until it closes in October, which will reduce the cost. In Germany, the government pays at least 60% of wages for the time a worker is not working. Employers can pay staff for the rest of their usual hours if they are worked.

Allowing short-time working with state subsidies is a policy that economists say Britain could adopt. Several other countries across the EU have similar schemes, including Spain, Italy and France. Madrid plans to bring its scheme to a close next month, but Italy has extended its scheme until December and France for two years.

The National Institute of Economic and Social Research reckons that extending the furlough scheme in Britain until the middle of next year would cost just £10bn, and could pay for itself – as unemployment benefit claims would not rise and furloughed workers would pay taxes and keep spending in the economy.

The government is, however, reluctant. Sunak argues that it is unhealthy for people to remain away from the jobs market for long periods, and that it is better for them to find work in parts of the economy that are coping better with the “new normal” of physical distancing. It is an opinion shared by Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England.

The chancellor is also counting on a £1,000 bonus helping employers to retain furloughed workers, and billions of pounds of other tax and spending measures, including a new “kickstarter” job creation scheme, funds for retraining, and more staff at Jobcentres helping people transition into new lines of work.

The fear is that the jobs market will take much longer to adjust as the pandemic continues to slow Britain’s economic recovery, leaving millions unemployed and suffering long-term consequences.

Alfie Stirling, head of economics at the New Economics Foundation, said: “It would make more sense to have a concrete cliff edge in October if we had a hard, evidence-based reason to know there would be no continuation of the virus beyond October. But that doesn’t exist.”