The chancellor is a one-man brand, a designer label on to which aspirational values are projected via slick social media posts that bear more resemblance to David Beckham launching a new aftershave than a politician touting an economic stimulus plan. When Conservative MPs ask why it’s Sunak’s name and not their party’s on all the promotional blurb, the blunt response is that people like “brand Rishi” better.

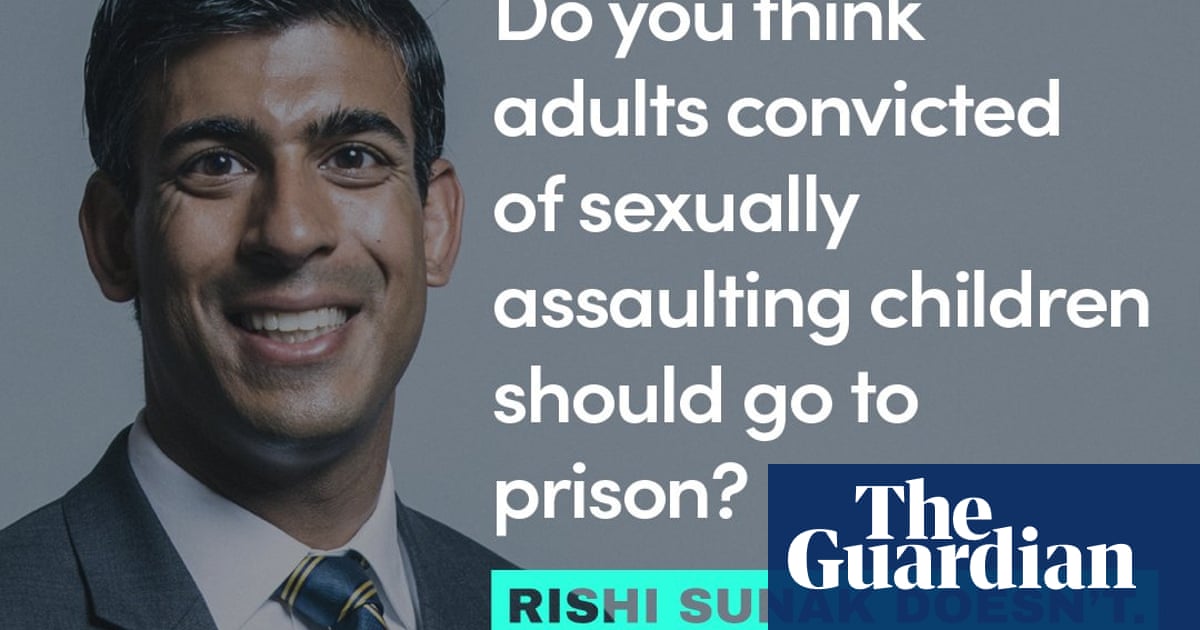

But as the warm glow of the Treasury’s skilful early response to the pandemic fades to the chill of an autumn where one in three employers are reportedly planning redundancies, something has shifted. It is no accident that at prime minister’s questions this week, Keir Starmer read out an angry letter from a constituent of Sunak’s whose wedding planning business has been hard hit by Covid restrictions, and who accused the government of closing its ears. The point was hammered home when Labour cheekily released a parody “brand Rishi” post online, bearing the slogan “Millions of jobs at risk” over the chancellor’s familiar handwritten signature and the tagline “Rishi’s name is all over it”. Boris Johnson is no longer Starmer’s only target, which reveals something both about how the political landscape has changed this summer and about Labour’s approach to the hard road ahead.

On one level, Starmer is simply hedging his bets. There is already a strangely exhausted, midterm feel to Johnson’s still fledgling government, which in just nine months has endured a whole parliament’s worth of existential challenges and can’t even take its whopping parliamentary majority for granted any longer. Downing Street successfully defused a threatened backbench revolt over emergency coronavirus powers this week, but only by offering MPs more say over national restrictions in the future. The clear message is that the prime minister can no longer act with impunity, but will have to negotiate any further measures with the wilder-eyed parts of the libertarian right.

Theresa May could doubtless testify to how exhausting that can be. Amid speculation that the prime minister simply may not last a full term of this, Labour can no longer safely assume it’s Johnson they will be facing at the next election. Put crudely, it’s now in their interests to ensure any mud sticks to his likely successors too.

But whoever was leading the Tory party, targeting its economic credibility would still have had to be part of the plan. Every serious analysis of last December’s cataclysmic defeat has suggested three key failings: Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, the fact that voters didn’t trust the party on the economy, and its Brexit position. Having distanced himself from Corbyn and edged ahead of Johnson on leadership qualities, Starmer is simply working his way methodically down the list. It may all feel a bit ploddingly obvious. But it’s telling how seriously thoughtful Tories now take the threat from Starmer, even as parts of the left insist the leader they never wanted is failing in ways that mysteriously cannot be evidenced in polling.

Sunak’s message that Britons must learn to “live without fear”, rather than hiding away from the virus, was music to the ears of those Tories who fear that a second lockdown would kill any economic recovery stone dead. But while the chancellor is riding high within his own party, his so-called winter economy plan has begun to prompt questions in the outside world about how much substance there is behind the style.

Many in business would accept that job losses are inevitable when furlough ends in October, and that firms or sectors that were floundering even before the pandemic should now be allowed to fail. But even the most flint-hearted must wonder why there isn’t more support for those with a bright future beyond Covid: restaurants and bars, theatres and music venues, an events industry that would be flourishing if it could open properly. When this is over, will there not be weddings to plan?

There are grumbles too about the Treasury’s new job support scheme, pitched as being modelled on a German scheme that aims to avoid redundancies in a recession by subsidising the wages of workers willing to take a temporary cut in their hours. But while Germany’s programme aims to share what little work there is around during a slump, keeping workers attached to their companies in expectation of better times ahead, under Sunak’s scheme it could work out more expensive for employers to keep two workers on reduced hours than to let one go and give the other more hours. If it doesn’t reduce redundancies, some wonder, what’s the point?

Even a chancellor who has excelled at floating magisterially above his own government’s mistakes may struggle to avoid blame if switching off the economy’s life support mechanisms this autumn triggers job losses on the scale some fear.

None of this, of course, belies the exceedingly long and hard road ahead for Labour. Sunak may look a little more mortal than he did, but his approval ratings remain sky high and the ratings of his Labour opposite number, Anneliese Dodds, remain alarmingly low. Restoring Labour’s own battered economic credibility will be the work of years, not weeks; and given the scale of last year’s losses, it is still hard to imagine Labour winning the next general election outright. For an opposition to succeed it is necessary, but very far from sufficient, for a government to stumble.

Yet putting Sunak in the spotlight suggests, at the very least, both confidence and clear-sightedness about what needs to be done. Power is starting to ebb away from the prime minister, which could be a blessing for an ambitious chancellor. Labour’s challenge now is to make it his curse instead.

• Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist