f the past year’s Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation prize was underwhelming, its successor is unapologetically esoteric. The four artists shortlisted for 2021 are Poulomi Basu, Alejandro Cartagena, Cao Fei and Zineb Sedira. The Deutsche Börse prize “recognises artists and projects deemed to have made the most significant contribution to photography over the previous 12 months”. Within that elastic remit, though, this shortlist is random, even by past standards.

Cao Fei uses site-specific installation and film to explore virtuality and its impact on the individual and society. Her characters exist in a liminal state between the real and the augmented, negotiating a world in which the future has already arrived and is loaded with uncertainty. Though she uses humour and surrealism, her created narratives are fraught with dystopian pressures, including digital atomisation and the increasing mechanisation of labour in her native China. It is difficult, though, to argue that photography is central to her practice and, indeed, to do so would risk diminishing the ambitious, multilayered nature of her vision.

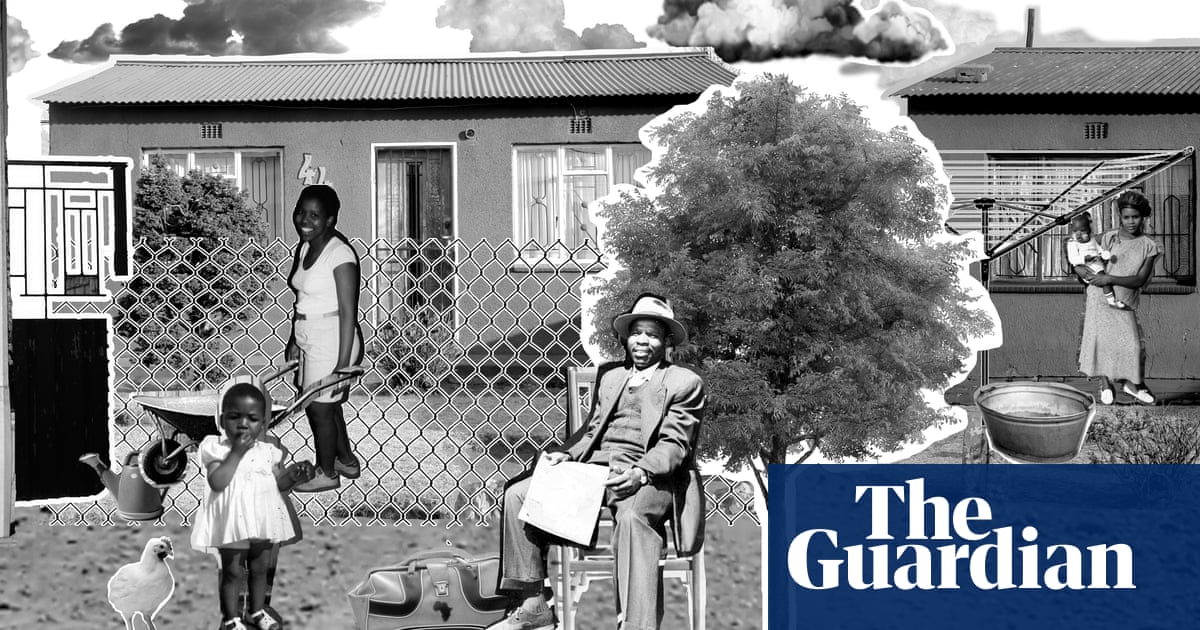

Sedira’s retrospective at Jeu de Paume in Paris used extensive archives and an installation to explore her French-Algerian identity and the complex, shifting politics of exile and belonging with reference to the more overtly radical pan-African liberation movements of the 1960s and 70s. She engages with complex subject matter that is utterly contemporary and yet resonates across postcolonial history. In her case, photography is part of much wider delineation of the personal and the political, though far from the essence of the project.

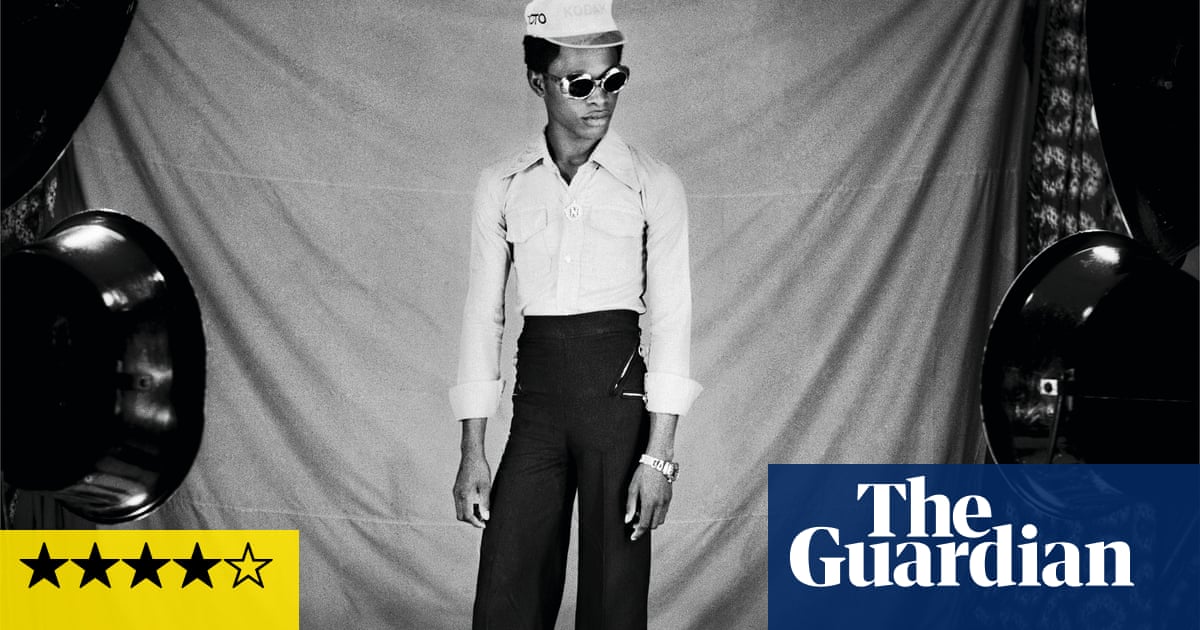

The other two artists have been nominated for books. Cartagena’s ironically titled A Small Guide to Home Ownership distills 15 years of work chronicling the relentless urbanisation of land in northern Mexico. Deftly using the how-to book model to which its its title alludes, it is densely packed and visually wide-ranging, referencing portraiture, illustration, landscape photography and advertising. Into this metaphorical mix, Cartagena drops pertinent personal stories, including his brother in law’s struggles with bureaucracy as he attempts to buy his own home. As far away as one could imagine from the detached style of, say, Robert Adams, the book nevertheless addresses the similar concerns, not least the environmental impact of relentless urban development on the environment.

In her book Centralia, Indian artist and activist Poulomi Basu casts light on an overlooked conflict between the Indian state and the Maoist People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army, which is made up of volunteers from a beleaguered indigenous community. Basu moves effortlessly between traditional documentary and a heightened, almost hallucinatory approach that reflects both the brutality of the conflict and the state propaganda that feeds on half-truths and manipulated “facts”. It is a powerful work that uses documentary photography, while simultaneously questioning its ability to grapple with the often digitally driven complexities of contemporary post-truth geopolitics.

While the 2021 Deutsche Börse shortlist is to be applauded for being truly international, questions remain over its validity as a photography prize. There has been an abundance of vital and challenging work produced over the last few years by artists whose prime medium is photography – The Coast by Sohrab Hura; Evokativ by Libuše Jarcovjáková; My Birth by Carmen Winant; The Pillar by Stephen Gill; Somnyama Ngonyama by Zanele Muholi, to name just a few off the top of my head.

In this context, this year’s shortlists seems random and wilfully unrepresentative of the medium. I’ve made this point in different ways in the past, but it seems worth reiterating: the issue at stake here is not purely semantic, as some will argue, but may be one of definition. How far can the Deutsche Börse prize stray from photography and still claim to be a photography prize? Or, to put it another way, what is the Deutsche Börse photography prize for?