am due to give evidence to the official inquiry into undercover policing early next year, as a “non-police, non-state core participant”. I was targeted by undercover officers for some 30 years, including when I was an MP.

This week the government’s new covert human intelligence sources bill is being debated in parliament. What troubles me most about this issue, however, is the clear abuses practised by undercover officers involving people I know well.

Kate Wilson was at primary school in London with my two sons. Our families shared holidays. She is not a criminal; she is a principled ecological activist. But she was targeted by undercover officer Mark Kennedy, who formed an intimate and what she afterwards described as “abusive” relationship with her over seven years. Kennedy even reported back to his superiors on contacts with my family when I was a cabinet minister. But why were police targeting Kate in the first place? Do they view green campaigners the same way they see drug barons, human traffickers, criminals and terrorists?

Doreen Lawrence, now a fellow Labour peer, was a law-abiding citizen when her family’s campaign to discover the truth about her son Stephen’s brutal murder was infiltrated by undercover officers. Why were they instead not targeting the racist thugs who killed him?

Undercover officers attended anti-apartheid meetings in my parents’ living room from the late 1960s to the early 70s; and, later, they reported back that I had spoken at anti-racist events when I was an MP in the early 1990s. Again, why were they not targeting the criminal and oppressive actions of the apartheid state responsible for, among other things, firebombings in London?

Why did they show no interest whatsoever in discovering who in South Africa’s Bureau of State Security was responsible for sending me a letter bomb, in June 1972, capable of blowing my family and our London home to smithereens? Thankfully there was a technical fault in the trigger mechanism.

Why were they not targeting Nazi groups responsible for attacks on black, Jewish and Muslim people, instead of spying on the Anti-Nazi League?

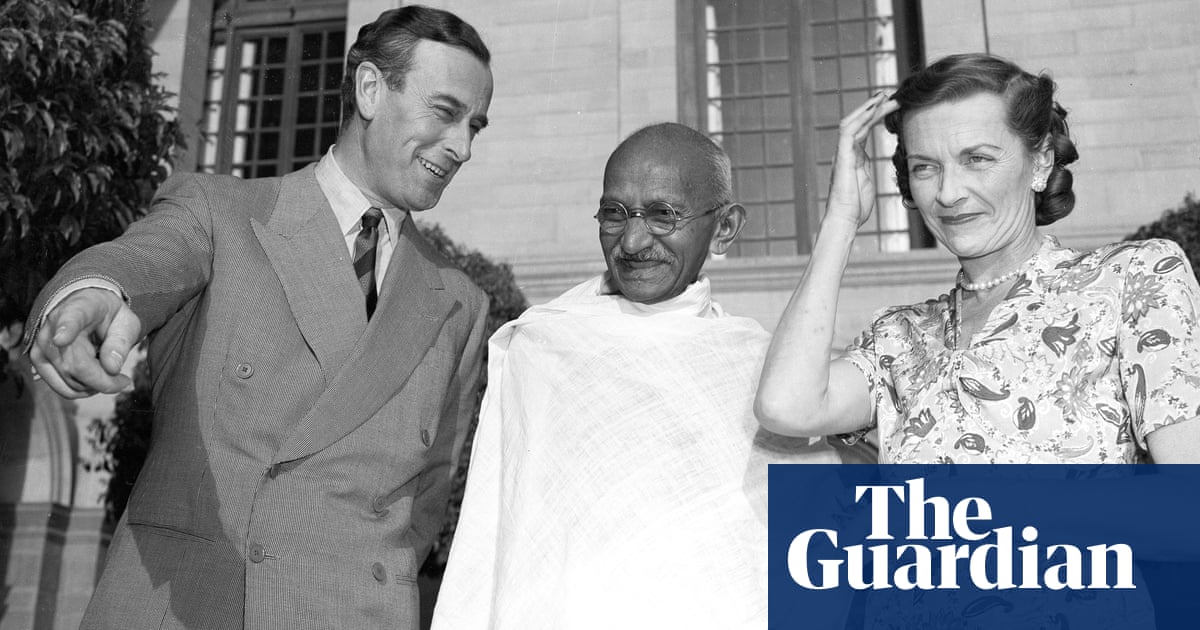

In each of these cases, the police were on the wrong side of justice, on the wrong side of the law, and on the wrong side of history. Infiltrating the family of a climate-change activist instead of helping combat climate change. Covering up for a racist murder instead of catching the murderers. Harassing activists campaigning for Nelson Mandela’s freedom instead of pursuing crimes committed by the apartheid state.

There was also a systematic pattern of deceit and exaggeration by undercover officers. The man known as “Mike Ferguson” claimed to be my “number two” when I chaired the 1969-70 campaign to stop tours by all-white apartheid rugby and cricket teams. This was a straight lie. I had no “number two” – and if he is the person I vaguely recollect, he was on the periphery of those around me.

Ferguson and other undercover officers claimed our campaign intended to attack the police at Twickenham. A lie. They claimed we planned to sprinkle tin tacks on the pitch. Another lie: we ran on to pitches in acts of nonviolent direct action and were always at pains to avoid personal injury to players – though sometimes we were beaten up ourselves by rugby stewards or police. Undercover officers also played agent provocateur on occasion, daring militant but nonviolent protesters into criminal activity.

Fortunately, Kate Wilson’s early eco-activism helped pave the way to the Paris climate agreement. We stopped the 1970 all-white cricket tour, and helped bring down apartheid. The Anti-Nazi League, of which I was a founding national officer, succeeded in destroying the far-right National Front. But why were undercover police officers trying to disrupt us, diverting precious police resources away from catching criminals?

I do believe there can be a need for undercover officers. When I was Northern Ireland secretary from 2005 to 2007, I met undercover officers doing brave work trying to prevent dissident IRA groups from killing and maiming. I also signed surveillance warrants to prevent Islamist terrorists bombing London.

But where to draw the line? How do you stop legitimate undercover police or intelligence work sliding into the illegitimate? Even in our era of modern reforms – including legislative accountability for the first time – police and security chiefs have made a habit of getting it wrong. Putting nonviolent Extinction Rebellion on a list of terrorist groups hardly inspires confidence.

The covert intelligence bill doesn’t even begin to answer any of these key questions. Unless it is amended it will pose a serious threat to liberty and will be an invitation for action-replays of the malevolent use of undercover security work to disrupt human rights, anti-racist and environmental campaigns.

• Peter Hain is a former Labour MP and cabinet minister. His book Pitch Battles: Sport, Racism and Resistance is published on 1 December