n the midst of bleak, autumnal lockdown, a sudden sense of liberal optimism is in the air. Joe Biden has defeated Donald Trump in the US presidential election, and Boris Johnson’s bullying grand vizier, Dominic Cummings, has been ejected from Downing Street. There are briefings that a politics of civility and decency is returning to Westminster.

Is November 2020 to be the month in which the culture wars that began in 2016 finally begin to burn out, and 2021 the year in which the successful rollout of a Covid-19 vaccine unites a formerly divided country? The former chancellor George Osborne greeted Biden’s victory by tweeting: “Whether you’re on the left or right: moderation, integrity, seriousness and the mainstream are back.” Coming from the chancellor who introduced a decade of austerity, this should give pause for thought.

The winners of last week’s No 10 power struggle appear to be plotting something akin to a Cameroonian restoration. It is no doubt true that Johnson had grown tired of the aggression and arrogance with which Cummings and his sidekick, Lee Cain, prosecuted their internal battles. Their contemptuous treatment of Conservative MPs was stoking fires of rebellion on the Tory backbenches. But the principal motive for ordering Cummings to pack his cardboard box last Friday was surely that Johnson simply agrees with his new spokeswoman, Allegra Stratton, and his fiancee, Carrie Symonds: the time has come to shift shape once more.

With the Brexit transition period coming to an end and Biden heading for the White House, a new “Boris” – or rather an updated version of an old one – is required for 2021 and beyond. The unlikely tribune of the northern working class is to be replaced by the former mayor of London, a more liberal, environmentally friendly sort of chap.

The 10-point “build back green” plan, which Johnson is expected to unveil this week from his self-isolation, will put down a marker. At the Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow next year, the prime minister will burnish his internationalist credentials. A Brexit deal, assuming one is achieved, will see the UK positioned as ally and friend to both the European Union and Biden’s United States, as Trumpian disruption and overt nationalism is discreetly ditched. Tory politics will soon begin to look a little more like it did in the world before 2016. As Osborne put it recently, it is time for Johnson to “morph again, and head for the political centre”.

There are of, course, very good reasons to be relieved that the type of politics represented by Cummings appears to be in retreat. A Labour party statement, identifying a legacy of “bullying, deception, hypocrisy and hubris”, nailed some of them. Not surprisingly, the humiliatingly abrupt manner of Cummings’ exit also unleashed a wave of euphoria among those scarred by the Brexit battles of the last four years. Yet the left should have no truck with this restoration politics. There is a deeper and different significance to last week’s events, which Labour must not miss as the champagne emojis begin to disappear from Twitter timelines.

The association of Brexit with a reassertion of the values of working-class communities, neglected for decades, led eventually to the fall of the “red wall” seats last December. For Labour, the need to prevent that collapse becoming a historic realignment is existential. The sudden end of the Cummings era signals an opportunity, but it can be grasped only by acting on what he got right.

Cummings’ rise to an extraordinary level of power and influence was achieved through a combination of two insights. The first was that past Conservative governments had given people good grounds to believe that Tory MPs cared little about those in poverty or the NHS. The second was that, in swaths of Labour-voting England, particularly in the post-industrial north and Midlands, there was a deep nostalgia for a lost politics of solidarity – which was partly why the NHS had become so totemic.

As early as 2004, during the referendum campaign on a proposed north-east assembly, Cummings was successfully mining that progressive nostalgia, and putting it to work in the interests of a nascent populist right. His slogan of that time, “More doctors, not politicians”, became the precursor to Vote Leave’s “£350m for the NHS”. Cummings rerouted a desire to bolster the fraying social fabric within communities and deployed it against the disinterested “elites” of Westminster and Brussels.

It was cynical and manipulative, but it helped Cummings and his Vote Leave faction develop an acute understanding of the class dynamics of 21st-century English politics. Which is why those Conservative commentators who fret over a possible return to the Tory “southern comfort zone” are right to be worried.

The signs are that the government’s coming pivot to “the centre” will be accompanied by a renewed emphasis on deregulation, low taxes and as small a state as can be managed, post-pandemic. Rishi Sunak, for whom Stratton worked before joining the No 10 team, is an orthodox economic liberal and a deficit hawk. Even before the Covid pandemic forced the Treasury to take on huge levels of debt, the chancellor was wary of a shock-and-awe “levelling up” investment programme for the north. There are reports that he is resisting pressure to offer generous long-term funding for a jobs-rich green recovery programme.

On the newly emboldened Conservative backbenches and in the cabinet, there will be fierce resistance to redistributive tax rises for the better off. Without them, and without a large-scale programme of state investment in the regions, red-wall constituencies may conclude they have been used and abused once again. A culture war will not cut it.

Meanwhile, Labour must resist the temptation to say “I told you so’, and learn the lessons of Vote Leave’s successes with humility. The errors of the late 90s and 2000s, which first let Cummings in, must not be repeated. Starmer has excelled in his lawyerly dissection of Johnson’s handling of the pandemic. This is his comfort zone. But with a vaccine on the horizon, a radical post-Covid vision for England beyond the south-east is needed.

Rethinking what northern nostalgia is truly about, and disentangling a residual memory of more cohesive, egalitarian times from the distortions of Brexit, would be a first step. The left should not stop thinking about Dominic Cummings just yet.

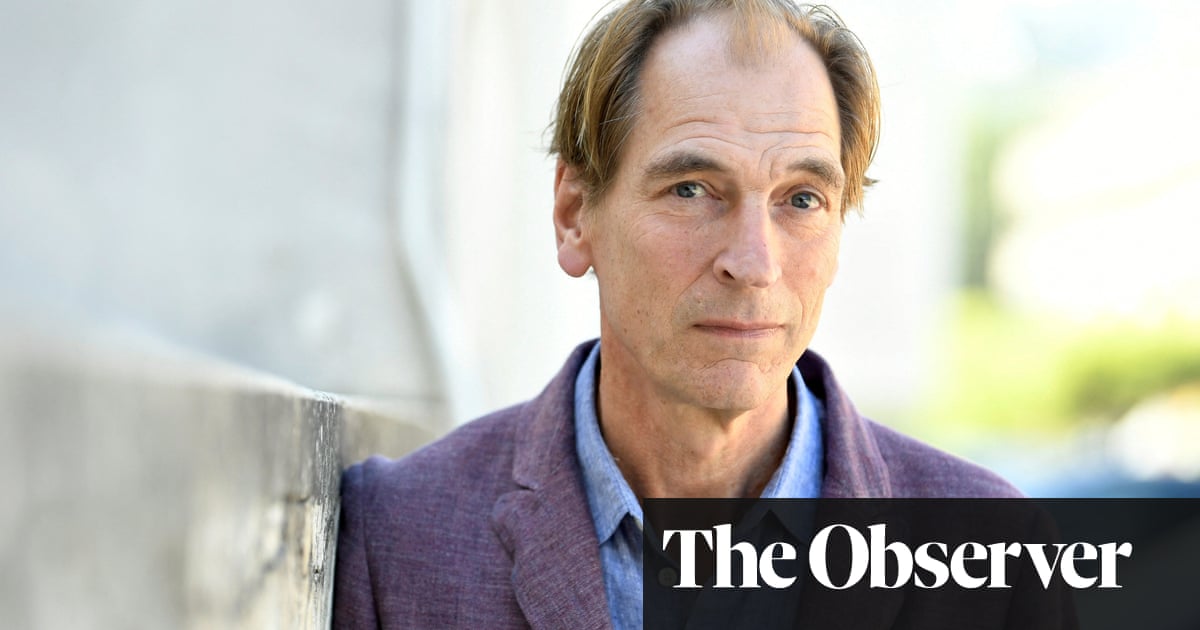

Julian Coman is a Guardian associate editor