efore Tracey Emin, there was Traci Emin. That was how the young woman who would go on to be a star of conceptual art signed her name on a stark black-and-white woodcut poster back in 1986. It was for her degree show at Maidstone College of Art, where she earned a first in printmaking. It caught my eye a year ago while I was exploring her studio archive.

The woodcut – showing two desperate lovers clinging together in a dark night of the soul, the woman with an anchor tattoo – is part of a previously unseen hoard of Emin’s all but forgotten early work that reveals a different side of the artist from the one most people think they know. Much of it is lost and exists only as slides, the originals having been destroyed, she thinks, by a former boyfriend. They show the sincere and skilled artist Emin was before she became a household name and an infamous figure to many. When I saw these student works, I wanted to get them published so that everyone else could encounter that intense young soul. I was thrilled when she let me include them in a new visual book about her art.

In the 90s, Emin became the eloquently drunk spokeswoman for a generation that seemed to despise craft and revere Marcel Duchamp’s idea of the readymade artwork. Her display of her chaotic bed at the 1999 Turner prize – littered with used condoms, fag butts, joints and booze bottles – is for many people the most in-your-face readymade in recent memory.

But Emin had a secret: she wasn’t really a follower of Duchamp at all. Nowadays, she sees him as a bad painter who invented conceptual art to hide his lack of ability. And she puts that belief into practice. In the last few years, Emin has been painting like a person possessed. A lot of this has been done at her mountain estate in Provence, where she can work in splendid isolation in a low, modest studio nestling in a little valley where there’s little to disturb her but the chirping of cicadas.

When I visited her there a few years ago, she rolled out some of her latest canvases on the parched late-summer grass beneath the olive trees. I was electrified. The freedom in the way she smacks paint on to canvas, the raw violence of real life she manages to keep in her colours – both are a wonder. What puzzled me was how she got here, how an artist who made her name with conceptual work had transformed herself into a thrilling painter.

And here now, on that rainy day in her London studio, was the answer. Her creative manager Harry Weller pulled early work after early work up on screen: women alone in bedrooms, Christ on the cross, a harbour full of sailing ships, an enigmatic love triangle, friends sharing wine on the beach. In fierce monochrome and punchy colour, I saw that Emin was always a painter and a printmaker. Where she is now is where she started out, in front of a blank sheet or canvas. She filled it then, as she does now, with untamed life.

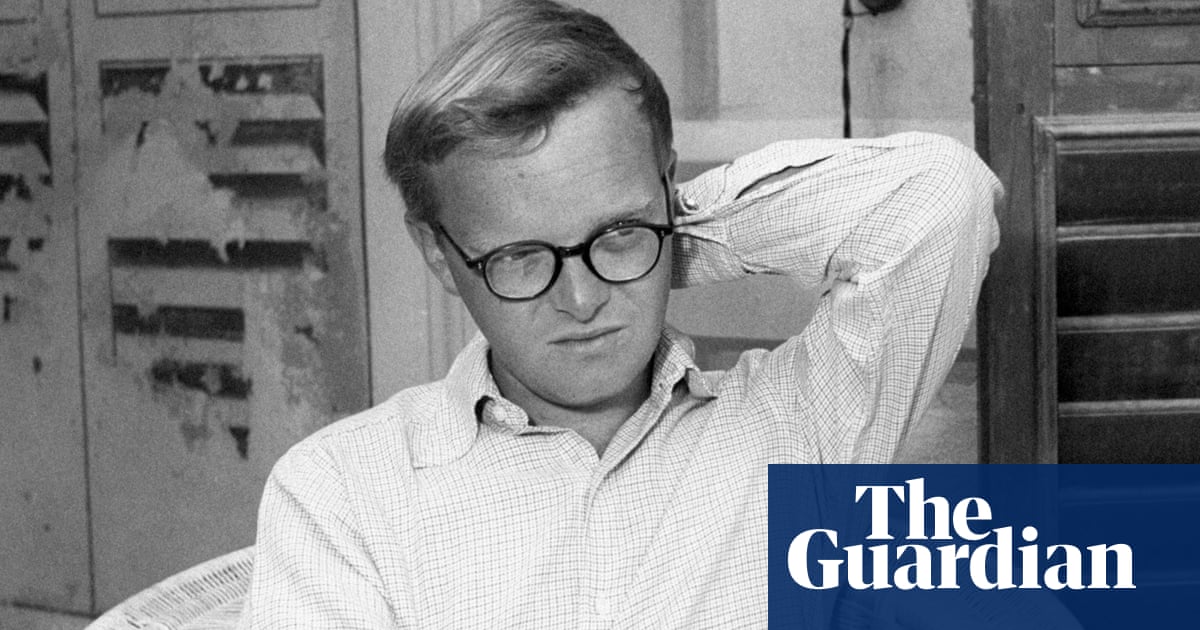

The artist Billy Childish, her then boyfriend, appears in one of her powerful early woodcuts as an almost Frankensteinian character: big, brutish and hyper-masculine. It’s called Billy, Drunk, Learing With a Drink in His Hand and captures him lurching about a nautical, half-timbered pub with an anchor on the wall. It’s a great example of what might be labelled Emin’s seaside expressionist phase.

In a whole series of similarly rough-edged woodcuts, she creates a romantic vision of her hometown Margate and the seaswept Kent vista: yet more desperate lovers, adrift between fishing boats and boozers. The content may be local, but the inspiration is German, as she translates the style of such expressionists as Ludwig Kirchner, Käthe Kollwitz and Oskar Kokoschka into a myth of her own life. Her tempestuous relationship with Childish haunts these works. One is that woodcut for her degree show. It is called, with a weirdly poetic ring, Jaw Wrestling.

Emin effectively left school at 13 and spent her teenage years hanging around Margate’s more dubious haunts. All this is recorded in her storytelling artworks, such as Why I Never Became a Dancer. But there was another side to her story: she had a born artistic talent. She still owns a clay model of a fruit stall she made on one of her rare visits to school, a beautifully crafted object, like a piece of painted terracotta you might see in a Christmas crib in Naples.

It’s clear why Emin got into Maidstone to study printmaking – and her woodcuts show why she was awarded a first-class degree. She hasn’t just mastered this medium, she also uses it to convey an original vision of life as an extreme drama of loneliness and love, with people whose mask-like faces are hewn from pain. From there, in 1987, she got on to the prestigious painting course at the Royal College of Art in London.

Emin says that, when she was at the RCA, she got interested in the abstract expressionist painter Cy Twombly, thinking the artist was a woman. But, too driven by her own life, she had not yet ventured into abstraction. Emin’s father, Enver, was Turkish Cypriot and, in the mid-80s, she went off to explore Turkey for herself. A lovely series of watercolours records this search for her heritage, which resulted in a love affair with a fisherman.

A sense of adventure echoes through these works, with their bright colours sometimes flowing over newsprint borders. Istanbul seems at first glance a charming cityscape, almost a tourist view – but look closer and you see inside the city, glimpsing a woman in bed and an old-fashioned kitchen. Other scenes home in on traditionally dressed women in rooms with antiquated wood stoves. Their inner space is explored as evocatively as their outward demeanour.

Other works glorify a man and woman making love with Lawrentian intensity in the open air. A narrative seems to emerge of illicit love and rivalry, a tangled emotional soap opera. It is the beginning of the abandonment that runs through Emin’s art, from that detritus-strewn bed up to her latest paintings.

In truth, Emin never stopped making pictures. The passion for drawing and painting, so evident in these early works, meant she could never become a purely conceptual artist. Some of her most compelling prints are harshly scratched images of funfairs and graveyards – and they all date from her Young British Artist years. When she started drawing birds, she remembers, people thought she was making some ironic point. “But I wasn’t. I was just drawing birds.”

Actually, Emin even claims her bed is “a painting”. It’s true that when I watched her put it together at Tate Liverpool a few years ago, she laid on the decaying condoms as if putting the final touches to a canvas. She even flicked on the wrinkly tights like an action painter. Emin’s real artistic evolution is not from readymades to painting, but from expressionism to abstract expressionism. I can’t wait to see what she paints next.

• Tracey Emin by Jonathan Jones is published by Laurence King books on 26 November, price £14.99.