andra Rhodes was doing a yoga session with a friend in the early weeks of the pandemic when she realised that something was wrong. “It’s a funny story,” she says. “We were lying on our lilac mats in my rainbow penthouse, and I was breathing deeply – and my stomach felt full. And I thought, why is it full? I haven’t had a meal today.”

It turned out she had a tumour. “It was in the bile [duct] and going into whatever’s near it,” she says, vaguely. Treatment involved weeks travelling across a locked-down London for chemotherapy, followed by an immunotherapy regime that she is still on, even though she is happy to say that the tumour is in full remission. Her first thought after diagnosis was “to get my will in order with a power of attorney that included a do-not-resuscitate order. I was very lucky because I had no pain whatsoever. I just got very tired while I was having the chemo.”

Not many people could make an anecdote out of a cancer diagnosis – but Rhodes is no ordinary person. At 80, she is a blaze of neon pink, fully made-up and strung about with beads the size of boulders, on a screen that gives a tantalising glimpse of that rainbow penthouse. Crammed with paintings, fabrics and ceramics, it sits on top of the Fashion and Textile Museum in the south London district of Bermondsey, which Rhodes opened in 2003 after hiring the Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta to convert an old warehouse.

Our conversation is scheduled for first thing in the morning because that’s when she feels freshest. “Go on,” she urges, “you can ask me anything. Anything at all.” Could it be, I venture, that Dame Zandra does the lockdown thing of dressing from the waist up? “Well,” she says, “I’m not in high heels, so I think at the moment the effect is that I’m one of those old ladies who might look right at the top but are in trainers at the bottom.” Then she lifts one foot and waggles it in front of her screen – it is indeed clad in a trainer, but the pinkest, sparkliest one you could imagine.

Rhodes has been one of the UK’s most sparkly celebrity designers since she began to make her name in the late 1960s. The list of people she has dressed is a 20th-century hall of fame, from Barbra Streisand to Freddie Mercury, Princess Diana to Diana Ross. She has made guest appearances on Absolutely Fabulous and the Archers – and cooked sausages on Celebrity MasterChef. She turned up at Buckingham Palace in 2014 with a large rhinestone egg on her head, to be invested as a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Princess Anne, who had worn a Zandra Rhodes dress, in fairytale lace, for her official engagement photo 41 years earlier.

Her investiture hat was so over-the-top that one might almost suspect her of sending up the occasion, but she insists she is a staunch royalist, who would love to be let loose on the Duchess of Cambridge. Princess Diana, she says, was a dream to work with. She was “very, very shy” and dressing her gave a glimpse of the pressure she was under. “I made her white wrap dress, and she said she needed to know that it wouldn’t fall open and show her legs if she got out of a car, ‘Because, you can be sure that when I get out of that car, there’ll be people waiting at just the wrong angle to get me.’”

In the days before she settled for perma-pink, Rhodes’s own chameleonic styling occasionally got her into trouble – most memorably with Diana Ross. The singer turned up for a fitting in her London shop, and they hit it off so well that Rhodes was invited to the concert and to drinks afterwards. Six months later, she was driving through Beverly Hills with a friend when they spotted Ross getting out of a car. “My friend said: ‘Go and say hello,’ so I did. And she gave me this cold, cold stare, and said: ‘If you come one step closer, I will close this garage door on you.’”

Rhodes beat a hasty retreat, but when she got up the next morning, her bleary-eyed hosts told her the star had rung at 3am to apologise and fix up a breakfast date. “You see, in my shop I was wearing a white turban. What she saw getting out of the car and walking towards her was a girl with green hair with feathers stuck on the ends.”

Wasn’t there a bit of her that might have liked to have gone incognito while dealing with the indignities of cancer treatment, I ask. She responds by recalling a short-lived flirtation with dyeing her hair brown. It happened about 20 years ago because her boyfriend was very conservative, she says. “But it lasted for one week, until we went to a cocktail party and it was so embarrassing when people said they didn’t recognise me that it was easier just to be me. Also, I felt so boring. If I’ve got my hair and makeup on, it makes me face the day.”

Boring is a word that crops up a lot as she talks – it’s the yin to her exhibitionist yang. Her look-at-me styling isn’t just for fun: it’s a shop window for a self-confessed workaholic, who for decades produced two of her own fashion collections a year, as well as off-the-peg ranges on commission: bras and bathrobes for Marks & Spencer, tents and wellies for outdoorsy Millets. In between, she has designed bathmats for Japan, saris for India and has now teamed up with Ikea to produce a range of 26 items, the first of which was revealed shortly before Christmas: a frilly pink take on the firm’s signature Frakta bag.

When she talks about her work, Rhodes always refers to herself in the plural; it’s not a self-aggrandising “royal we” but an acknowledgment of the hive of busy bees over which she presides. She is joined on our call – from another address – by Kelly, who handles the business side of the conversation, allowing Zandra to concentrate on being Zandra. Kelly is one of “my girls”. Another, Hayley, works with her on her textile designs, while Lottie is a live-in student, who is helping her to archive more than 50 years of clothes and sketches. “We formed a household of two people, which is wonderful,” she says. “We can take turns at cooking because it gets terribly boring if you’re only cooking for one.”

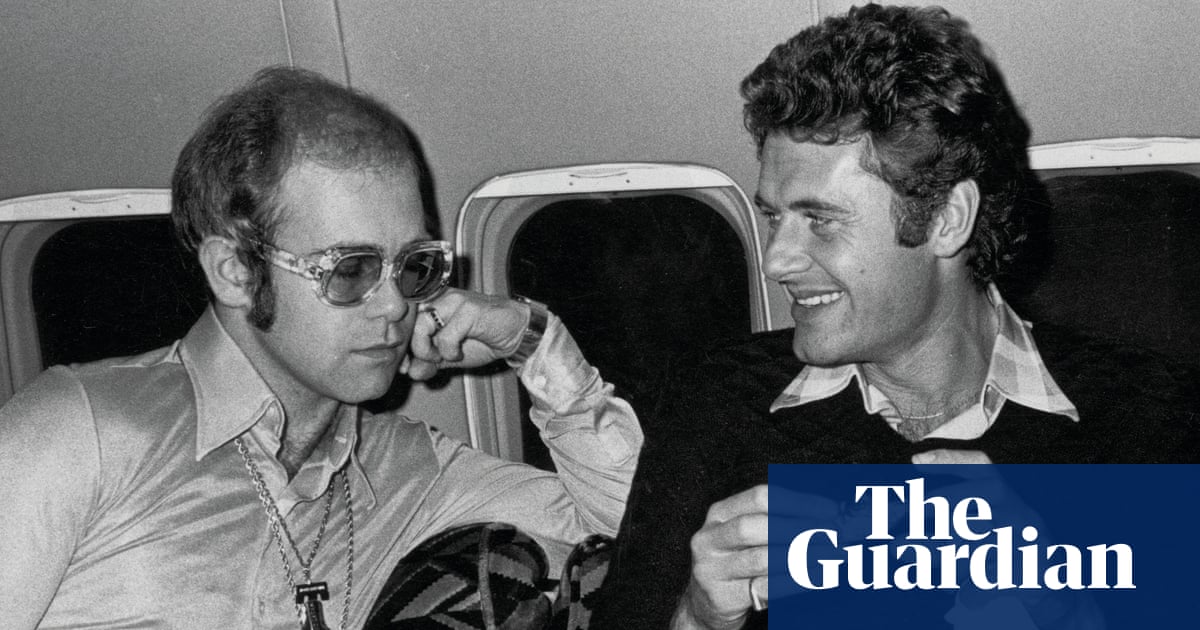

Which brings us to the other life-changing event of the past 18 months – the death of her longtime partner Salah Hassanein, an Egyptian-born Hollywood mover and shaker whom she met at a New York charity ball. It was for Hassanein that she conducted her short-lived experiment with going brown, and for the past 25 years she has spent half of every year at his California home, becoming part of the local social scene, and designing costumes for the San Diego Opera Company. He reciprocated by backing her change of direction in the 1990s, which involved shutting all her London outlets to concentrate on developing her museum.

She was swanning around India, as part of TV’s The Real Marigold Hotel, when she was summoned to his deathbed in the summer of 2019, forcing her to abandon the series. Since they had never married, and she had conducted her transatlantic life on work visas, she wasn’t allowed back to collect her possessions when his house was being cleared out. But about this, too, she shows not a jot of self-pity. “It was always understood that if I wasn’t with him, I was going to pack up essential things like, say, wonderful mirrored pictures and different artworks, but my poor secretary had to do it. They’ve all been shipped back to me now, so everything is here in London – and the memories of him as well.”

The Ikea commission brings her full circle back to her origins as a designer of home furnishing fabrics. She only moved into fashion because nobody would hire her, she says, even though she had been the star student of her year at art college. Reckoning that Carnaby Street was where it was at, she talked her way into a role designing fabrics for the cutting-edge boutique Foale and Tuffin. “I suppose I came into being with trendy Carnaby Street and Beatles,” she says, “although I never met a Beatle at that time.”

It was all very different from life in the Kentish town of Chatham, where she grew up, the older of two sisters, surrounded by her mother’s sewing magazines. Beatrice Rhodes had worked as a fitter in Paris for the couturier Worth before settling down to become a lecturer at Medway College of Design (now part of the University for the Creative Arts).

“She was a very exotic woman, who was very encouraging with my schoolwork,” says Rhodes, who talks often of her mother, but has always been less forthcoming about her lorry driver father. The couple met as ballroom dance champions, but the dancefloor proved to be all they had in common. “Truthfully,” Rhodes says, “I don’t think they should ever have got married”.

Her mother’s exacting work ethic extended to family holidays, where she would busy herself knitting, while her daughters worked on jigsaws – both of which activities would turn up as recurrent motifs in Rhodes’ designs. “I was just a very boring, hard-working student. I was always top in art and I worked hard to be top in all the other things,” she says of her schooldays.

At first, she thought she wanted to be an illustrator, and she still has sketchbooks from her childhood showing a precocious talent. But reluctantly, she followed her mother to Medway college, where a charismatic tutor lured her into textile design. From there, she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art, where she was introduced to the music of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and the art of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, while starting to experiment with the effect on fabric design of draping it around the human body. “I was proud to be a textile designer, and I did not feel I was inferior to a painter or a sculptor. It was my metier,” she later wrote. She graduated with first class honours, and sold her degree print to Heal’s.

In the four hand-to-mouth years after graduating (her designs were considered just too far-out for ordinary homes) she taught herself to cut fabrics, set up a print studio with her then boyfriend Alex MacIntyre, and created a home that was a homage to pop art – “a perfect world of plastic”. To pay the bills, she took part-time teaching jobs at art colleges, but hated doing so. Desperate to escape this new sort of boring, she set up a boutique in Fulham with a teaching colleague, Sylvia Ayton, and by the time it opened in 1967 she had already built up a buzz: Joe Cocker sang at the launch.

But the shop only lasted a year, and in 1969 she launched her first solo collection, investing a small inheritance from her mother – who had died when Rhodes was only 24 – in a networking trip to the US. There, she caught the eye of American Vogue, which hired the starlet Natalie Wood to model one of her designs. The glamorous yellow coat made from homely felt is now in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, along with several other gowns from that first collection.

The development of her signature style went beyond the clothes she was designing, to her own look. “I tell kids who are starting off that if you’re a designer, and you don’t wear your own things, then what are you selling?” she says. At first, it involved “lots of makeup and cheap rings”. She would buy “crazy colours” from Woolworths to paint her face, and looked so outlandish that Ayton once suggested that she was scaring customers away. Before long, her own makeup was mirroring her fashion collections – her eyebrows plucked bare to make a stage for the calligraphic monobrows of Chinese opera or the beaded lines of Masai culture, which she observed on her extensive research trips.

But mostly she led a low-key life, she insists. She has always travelled with a sketchbook in hand, returning to the constant anxiety of trying to craft high-fashion concepts from what she had seen: “People always think if you’ve got pink hair that you’re frightfully trendy, and you know what’s going on, when actually you’re usually working in a boring attic, trying to come up with ideas.”

It was in one of those attics, just off Portobello Road in west London, that Freddie Mercury and Brian May paid her a visit in 1974. “They came at night because I didn’t have a changing room, and I’d lift things off the rail and say: ‘Try it on. See how you feel moving around in it.’” The result of that fitting was the white pleated top – originally part of a wedding ensemble – that will always be associated with the Queen singer’s androgynous phase, and particularly with Bohemian Rhapsody. “Freddie was very quiet until he put on that top,” she recalls. “He only came once, but Brian had several outfits because for some reason his kept getting stolen.”

In 1977, she forsook glam for punk, releasing a collection – Conceptual Chic – that brought safety pins and sink chains into couture. No real punk would have given her the time of day, she points out. “I just saw it as an art form. It’s very difficult to cut a piece of fabric to look like a tear. We put beads on the slashes, and they looked lovely. I suppose you could say we put the glam into punk.” Decades later, Gianni Versace would repeat the look with Elizabeth Hurley’s famous safety-pin dress. Among the treasure Rhodes had shipped back from the US was a collection of “knockoffs” – pictures of designs that she felt copied her own. “Knockoff or homage, it’s whatever you want to call it,” she says.

For all the jokes about dry cleaners returning her clothes with the rips neatly darned and the safety pins in plastic bags, her buyers have always been aware that they were buying artworks (not least because Rhodes would tell them so, in notes printed on silk squares that she would send out with each commission). Every creation is catalogued and photographed; in a nod to Victorian lepidopterology, she calls them “my butterflies”.

How will she fare now that she is confined to her penthouse? She will continue to work as normal, she says, cooking for her “girls” when permitted to do so, and shooting off occasional letters to Radio 4 to complain about Archers plotlines. She’s ambassador for an upcoming touring art installation, Gratitude, to celebrate NHS workers, for which “we” are designing one of the figures.

Then there’s the business of setting her affairs in order. Everything she has ever made is recorded in “the bible” – her name for the sketchbooks she has carried with her around the world and that now sit alongside some 15,000 “butterflies” in 100 silver chests, waiting to be catalogued, distributed to museums around the world, or sold off to raise money for her foundation, which she set up last year to secure her legacy. She’s not going to allow herself to be forgotten as, she grumbles, so many great British fashion designers have been. “The fact is,” she says, “for some reason when I was diagnosed with cancer, it didn’t upset me – it made me pull my life together.”