crowd stands, spellbound, in a muddy square in northern Texas, firelight flickering on the faces in the evening darkness. A newspaper story is being read aloud by a lone speaker, and each man and woman strains to hear the words, mouths twitching with effort and emotion. It is a news report that tells of a group of miners in peril, trapped underground elsewhere, in some other benighted place.

It is an unusual scene of the sort that would perhaps be summoned up by a film director who earned his spurs in the world of news and current affairs. And it’s true, News of the World, a poignant western, was directed by Paul Greengrass, alumnus of British television’s old World in Action team and a big believer in the power of good reporting. But there is another reason for the rapt attention of this grimy audience: they are all listening to the voice of Tom Hanks, the nearest the liberal west has to a secular evangelist.

After 45 years in entertainment, Hanks, 64, has played a vast variety of roles, from hapless romantic leads in films such as Sleepless in Seattle to the blessed, Oscar-winning fool in Forrest Gump, and the funny man-child in Big. Yet more and more frequently he is called upon to stand for those fabled, vanishing adult values of decency and fairness. It’s always done with nuance, always he shows the strain. But Hanks, we know, is reliably on the side of the angels.

Towering Hollywood stars such as James Stewart and Henry Fonda have filled these boots before. Their honest American rectitude was a given for cinema audiences in the 1940s, 50s and 60s. In films such as Mr Smith Goes to Washington and 12 Angry Men, their ideals shone out. Since then, Will Smith has been allowed to join their ranks occasionally. It is something about not being too much of a matinee idol.

In the case of Hanks the mantle of approachable goodness has become a bit of a burden. He seems always to be asked about it. Even Barack Obama spoke of it, trying to give his pal more room to manoeuvre. “People have said that Tom is Hollywood’s Everyman,” the president said at a reception for the actor seven years ago, “that he’s this generation’s Jimmy Stewart or Gary Cooper. But he’s just Tom Hanks. And that’s enough. That’s more than enough.”

Hanks made his mark on another Democratic president when he hosted a star-studded show at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington to celebrate the inauguration of Joe Biden this month, telling TV viewers “the dream of America has no limit”.

Greengrass’s new film (released in the UK on Netflix on 10 February) is his second with Hanks, after the grim Captain Phillips, and it is a grand morality tale, painted with those shades of dirty grey we expect of the best westerns. Set after the American civil war, it stars Hanks as another captain, this time a combat veteran called Jefferson Kyle Kidd, who travels from town to town reading out stories he culls from broadsheet newspapers in return for a dime. It is a job that really did exist back in the west’s wilder days, although whether all the narrators were able to transfix their crowds as completely as Kidd seems doubtful.

The audiences were poor working migrants who, as Kidd tactfully puts it, had no time to read. Certainly, though, they would have had an appetite for new stories and for some sense of the world existing beyond their daily hardships.

The film is “very much worth seeing”, according to the Wall Street Journal critic Joe Morgenstern, partly because Hanks “dispenses his special quality of integrity from what seems to be an inexhaustible source”.

Whether Hanks is now deliberately taking roles that let him represent these virtues is guesswork. However, his production company, Playtone, does option and develop a lot of nonfiction stories of bravery; though it was Clint Eastwood who brought him to the screen in 2016 as Sully, the pilot who safely landed a plane in the Hudson River.

British critic, Jonathan Romney, said: “It is not clear if he has decided only to work on positive stories, as Dustin Hoffman is supposed to have done. But audiences clearly identify with him and root for him.” That’s why, Romney points out, Hanks was the obvious choice to play the American children’s entertainer and national hero Fred Rogers in A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood.

News of the World arrives at a time when film audiences are in even greater need of upstanding role models. Hanks’s “calming voice” is particularly welcome for Morgenstern when his nation “is no less bitterly divided” than it was after the civil war.

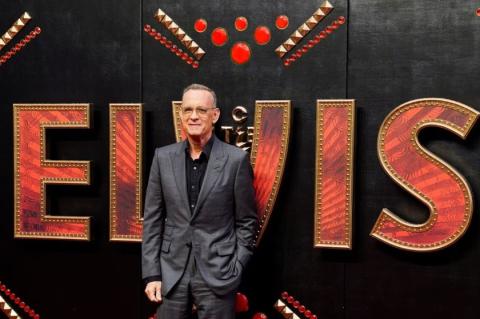

A year ago, the world gasped in horror when Hanks, in Australia to make a film about Elvis with Baz Luhrman, was diagnosed with Covid-19. His huge celebrity and apparent ordinariness brought the impending global crisis into sharp focus in a way no information campaign could have equalled. “No panic,” Hanks initially told his fans, before taking every opportunity since to underline the key precautions.

Where exactly did this calm maturity come from? The answer seems to be “from chaos”. The actor’s childhood in California was dysfunctional by any rubric. Four years ago, he told Desert Island Discs’ host Kirsty Young how difficult it had been. He was five when his parents divorced and the siblings were split up.

Hanks lived with his father, who took a string of restaurant jobs, moved a lot, and remarried more than once. It gave him, he said, a “need to fit in” and a persistent feeling he was “imitating the way he was supposed to be”.

After a failed first marriage in the 1980s to Samantha Lewes, mother of his children Colin and Elizabeth, stability arrived in the form of Rita Wilson, his co-star in Volunteers. The couple have been married since 1988 and have two sons, Chester and Truman. “I’m not a cheater,” Hanks has said of his relationship with Wilson. “I met her and I thought I’m not going to be lonely any more.”

Next to Hanks during his Australian quarantine was one of the aged manual typewriters he has collected for years – this one, neatly enough, made by Corona. It was a coincidence he talked about at Christmas to chat show host Graham Norton, regaling British viewers with an anecdote about sending the machine out to a boy on Australia’s Gold Coast who was being bullied for being called Corona.

The typewriter is a good emblem for Hanks, a dependable communicator who was associated with the value of newspapers before News of the World. In 2017, he played Ben Bradlee, revered editor of the Washington Post during the Pentagon Papers investigation. Steven Spielberg, director of The Post, could use the actor as journalistic shorthand for the ethical validity required.

Spielberg had deployed Hanks the same way two years earlier in his cold war thriller Bridge of Spies. Our hero was a remorselessly unexciting lawyer with a sense of fair play and a measured faith in the rule of law.

Hanks’s career is larger than this though. It represents decades of modern cinema. Just think of the catchphrases and memes: Gump’s box of chocolates, that piano keyboard dance in Big, and Wilson, the imaginary football “friend” in Castaway. “We have watched Hanks grow up on screen,” said Romney. “He has always been so comfortable in front of a camera. And he is interested in characters with real complexity; there is that slow-motion meltdown in Castaway.”

Whether he will ever convince as a screen baddie after being the voice of Woody in Toy Story for so long is unsure, although he had a bash in Sam Mendes’s Road to Perdition. For now, Hanks seems content to use his compulsion to “seduce” a crowd to spread valuable information, like Kidd in News of the World.

Will he surprise again by playing a villain, as Fonda did in 1968 in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West? Hanks recently told the New York Times he had recognised “a long time ago that I don’t instil fear in anybody”, although he reserved the right to be mysterious. Cinema audiences will soon get the chance to see for themselves when Hanks appears as the avaricious “Colonel” Tom Parker in Luhrman’s Elvis.