n 10 July 1992, a grisly stash of body parts was found in trash bags by a rest stop on the Garden State Parkway in New Jersey. The parts had been cut so cleanly that barely any blood could be found amid the sinew and bone. Over the next few years, similar scenes of horror would emerge in the region, leaving scores of clues about the character of the victims as well as the origin and method of their deaths.

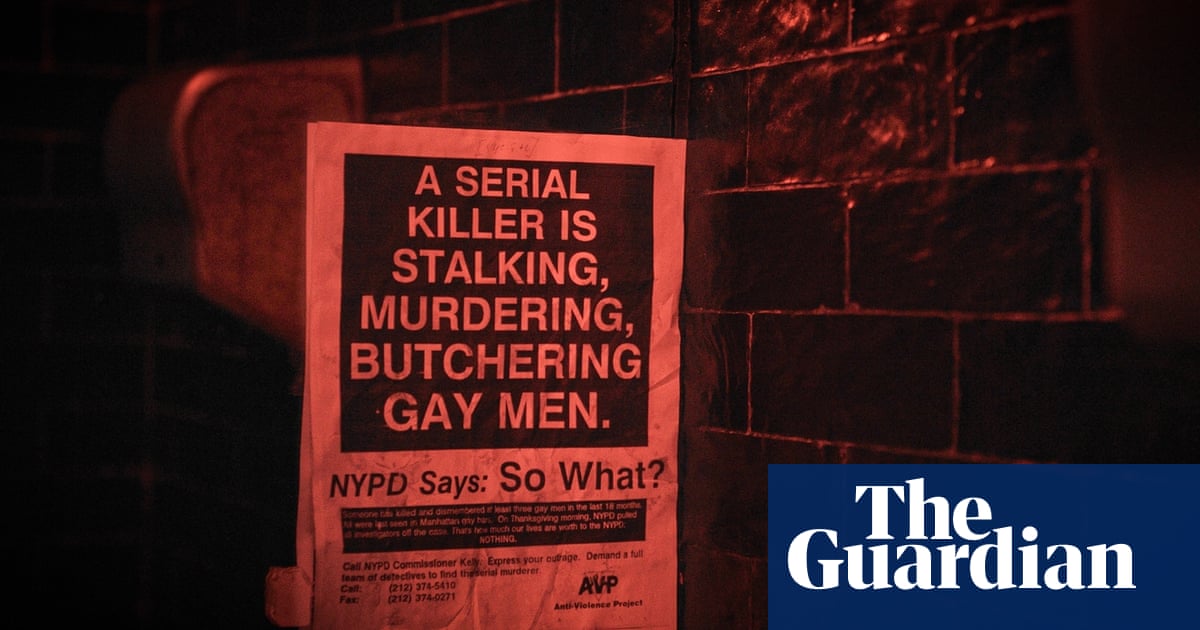

If this story had traced the common arc of serial killings, a wave of fear would have rippled through the communities most likely to suffer the next victim. But it didn’t happen that way. In fact, the people who were most at risk – in this case, gay men who met for hook-ups at New York City bars that served the community – were given no sustained or amplified warnings by either the authorities or the media, creating a safe space for the murderer to continue to wreak havoc. In fact, the case got so little attention relative to its horror that today few remember it, even within the gay community.

Now, three decades after the murders, journalist Elon Green has written a book titled Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York that goes beyond the facts of the story to reveal the larger issues that surrounded them. “It’s important for people to see how anti-queer bigotry manifested itself in this case,” he said to the Guardian. “They need to understand the stakes, not just for the victims but for the men who simply went to these bars during that period. There are systemic issues here.”

While LGBTQ people may still be at considerably elevated risk for violence, the level of peril and contempt was far higher in the late 80s and early 90s, when the bulk of the book takes place. Worse, that period represented the height of ignorance and fear about Aids, as well as the peak death toll in the gay community in the west, greatly impacting how the community was viewed. “Aids took what was, at best, a level of indifference towards gay people and turned it into revulsion,” said Green.

Consider, too, the general level of violence in New York City at the time. According to police records, there were 2,605 murders in the city in 1990, the single bloodiest year of the last 70. Between 1987 and 1994 the city saw a greater number of killings than in any other stretch in more than half a century.

I can speak to the frequency of violence in the gay community back then. In the early 90s, a man who lived two floors below me was bludgeoned to death by a guy he picked up in Central Park. In that same time frame, a close friend was gay-bashed into unconsciousness by a gang of young men, causing a days-long stay in the hospital, and I was punched so hard in the stomach outside a gay dance club I thought the guy must have used a hammer. Several years later, on a sunny day on Christopher Street (then the center of New York’s gay life), a man using an anti-gay epithet smashed my best friend in the head with a rock. When we ran across the street to tell a policeman sitting in his squad car, he surveyed my friend’s muscular build and said, dryly: “If I were you, I’d find the guy and beat the shit out of him.”

Meanwhile, the officer did nothing.

The story at the core of Last Call captures a time in the city, and in the lives of gay men, that seem far removed from the current one. Back in that benighted era, gay bars were often “the one refuge from the perils of everyday life”, said Green. “Their function was extraordinary.”

That the crimes originated in those spaces amplified the horror. At the same time, it was a particular type of gay man frequenting a specific kind of bar, who tended to be the victim in this case. Often, they were closeted men who were attending the city’s piano bars, including The Townhouse, which still exists. Green believes the double life led by some of the victims made them more vulnerable. “When you’re pushed into a situation where you’re pretending to be somebody you’re not, you’re more likely to take risks,” he said. “You’re more vulnerable to predation.”

The book spends much of its time telling the backstories of the victims, putting them at the center of the story rather than the killer. (The murderer, who is currently serving what amounts to a life sentence, rebuffed Green’s requests for an interview). “I don’t give a damn about the killer,” the author said. “Murderers are boring losers who made horrible decisions.”

At the same time, his book offers at least a hint of the man. “He was known for having a great sense of humor,” Green said. “At first I was very jarred by that. But I concluded that it’s not at odds with anything else. No one is the same person to everyone.”

The part of the book that does focus on the killer reveals horrific cases that preceded the ones he was later charged with. He got away with killing his roommate back in the early 70s, as well as with drugging a man he took home, then tying him up and assaulting him. As to why he eluded justice in these cases, Green said, “most likely the jury believed that this was a gay man attacking another gay man and they didn’t care about the circumstances. Given a chance to acquit, they took it”.

At the same time, Green said that he “ultimately realized that the killer (who was himself gay) was laboring under the same societal constraints his victims were. He simply handled it in a horrific and savage manner,” he said.

Despite all the evidence the authorities had about his crimes of the 90s, it still took a full decade to bring him to trial. While Green believed homophobia played a major part in that, he also said “decisions that law enforcement made contributed to the long delay. They simply didn’t follow certain leads.”

More, the fact that the bodies were left outside of New York City, and sometimes in different states, created jurisdiction issues that delayed justice.

In the epilogue to his book, Green says that, as a straight man, he had to ponder whether this was his story to tell. Eventually, he concluded that “when you’re talking about the history of queer people in America, or black people in America, you’re talking about the history of America. I think it’s a wonderful challenge to situate these stories in the larger history,” he said.

More, Green has long been drawn to “stories that I feel are going to disappear. Because of Aids, parts of queer history are in greater danger of disappearing than other histories.”

As well, the simple march of time has meant that no fewer than seven sources for his book died during the course of its reporting.

In a coda to the book, Green speculates on the likelihood that more victims of the killer may exist. In our interview, he said “there’s no doubt in my mind that there are more. It strains belief that the murderer would have gone as many years as he did without killing somebody that we know about. I also think it’s very likely that he murdered people when he went on vacations around the country. The horrifying thing that kept coming back to me as I was working on the book is that the victims that we do know, we only know about as a fluke. These body parts were not meant to be found. I’m sure there are more out there.”

Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York is out now