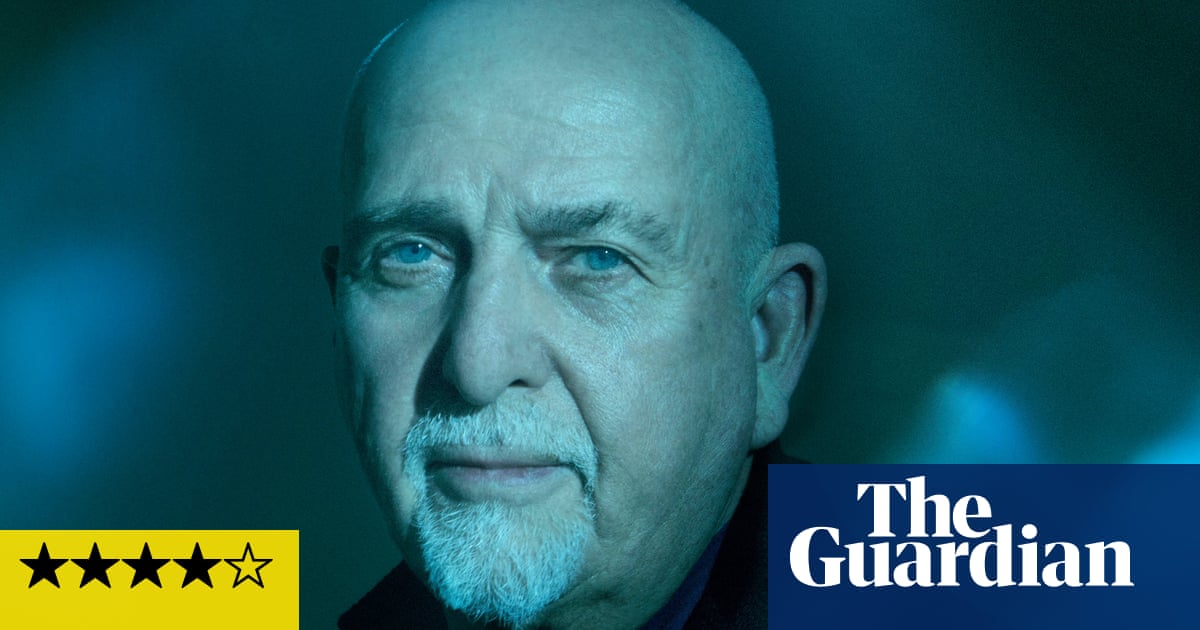

ll first albums come with some kind of backstory, but the backstory of the eponymous debut by For Those I Love – the pseudonym of Dublin-based songwriter/producer/vocalist David Balfe – is more harrowing than most. Recording was under way when Paul Curran, his best friend and fellow member of Burnt Out – an artistically ambitious punk collective who attracted attention in Ireland for their visceral depiction of youth in the working-class Dublin suburb of Coolock – killed himself. The opening track, I Have a Love, breaks the fourth wall to striking effect, three-and-a-half minutes in: “A year or so ago, I played this song for you on the car stereo in the night’s breeze / This bit kicked in with its synths and its keys / And you smiled as you sat next to me.”

Mired in grief, anger and bewilderment, For Those I Love is the second album in 18 months to deal with Curran’s passing: fellow Dubliners the Murder Capital said that “every single one” of the songs on their 2019 debut When I Have Fears “related back to his death in some way”, while the album shared its title with his favourite Keats poem. But while the Murder Capital set their lyrics to icy post-punk and raging guitar noise, Balfe’s key inspiration is the bedroom dance music and spoken-word vocals of the Streets. There’s an echo in his delivery of the spiky, heavily-accented sprechgesang approach favoured by the vital current wave of Dublin punk bands, the Murder Capital and Fontaines DC among them, but Balfe shares Mike Skinner’s fixation on apparently mundane details and his fascination with drunken, blokey high jinks, although it’s worth noting that For Those I Love offers a far starker, even nihilistic take on the old Geezers Need Excitement theme.

Balfe sets Curran’s death against a backdrop of late-teenage incidents and scrapes. He never allows the listener to forget that drink and drugs are a temporary escape, and never fails to underline exactly what they’re an escape from. Birthday is a grim depiction of Balfe encountering the body of a murder victim on his estate when still a child; The Pain or Top Scheme vaguely recalls Plan B’s Ill Manors in the sheer, scourging force of its class-conscious anger: “Our troubles and complaints are justified / it’s just numbers and stats until it’s your life.” In fact, he ends up taking issue with Skinner’s breezy approach. “Getting out seems no stage … I’ve felt this way since Turn the Page,” he snaps, a reference to a track from Original Pirate Material that urged the listener to forget the past and “walk away”. “There’s no walk away,” he adds, pointing out that it’s impossible to move on if you’re deprived of the opportunity to escape your surroundings.

Sometimes, the music tends towards the eerie post-dubstep of Burial, not least on the album’s emotional nadir, The Myth/I Don’t: a scattered assemblage of shrieking, echoing helium vocal stabs over which Balfe describes something that sounds suspiciously like a nervous breakdown. But there’s a reference early on to “dancing till day” at a “warehouse rave” and the album’s most potent moments come when he sets the lyrical darkness to music that sounds oddly euphoric, imbued with the spirit of old-fashioned helium-voiced hardcore. Stripped of its words, To Have You’s alternately glittering and surging electronics and samples of Bread’s Everything I Own (or at least a version of Bread’s Everything I Own – the samples are so sped-up it’s impossible to pinpoint their exact origin) would function perfectly as peak-time dancefloor material. Likewise, You Stayed/To Live: however bleak the circumstances that birthed the song – which recalls old band rehearsals and petty acts of vandalism in light of Curran’s death – it’s still entirely possible to imagine a festival crowd blithely going nuts to its cocktail of icy trance anthem synths.

It ends on a note of hope: “Those I love brought me back to health,” Balfe offers on closer Leave Me Not Love. Stitched together with muffled snatches of phone conversations , and ending on a note of hope, the album is an extraordinarily potent eulogy for Curran, its unflinching tone striking even in a world packed with confessional singer-songwriters spilling their guts. But it feels like more than just a cathartic vomiting-forth. For all the Dublin references, there’s a universality to the emotion; the music is finely-crafted enough to keep you returning, not matter how distressing the subject matter of the songs. There’s something here that that suggests Balfe could easily outrun the well-meaning, but limiting labels currently being attached to him – “Ireland’s potent poet of grief” – if that’s what he wants.

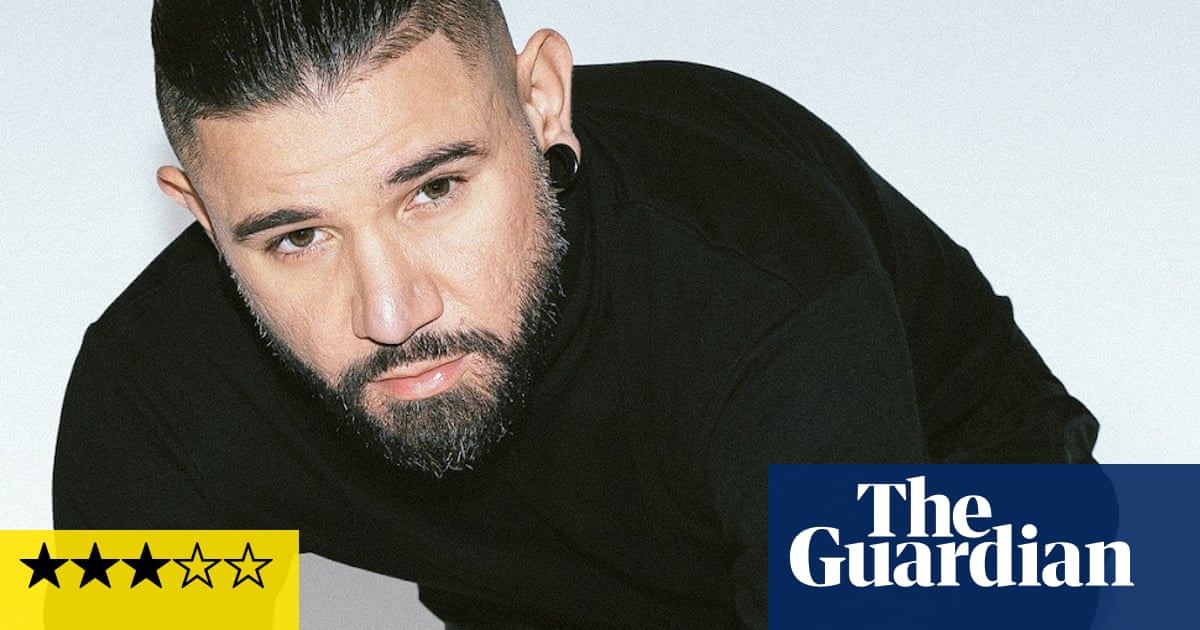

This week Alexis listened to

Lonelady: There Is No Logic

The return of Manchester’s Julie Campbell, recalling the era when her home city – or at least the denizens of Factory Records – fell in love with New York electro.