Peace agreements are delicate creatures. They require nurturing and care. The longer and more bitter the conflict, the greater this applies. And nowhere is this truer than in Northern Ireland.

Since the beginning of the month, Northern Ireland has witnessed its worst rioting in years. Violence has broken out nightly, leading to nearly 90 police officers being injured. Water cannons have been deployed for the first time since 2015. Petrol bombs flew over the walls dividing communities in West Belfast. The sad death of Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, may bring temporary respite out of respect for the monarchy, but the underlying issues are very much alive.

Violence creates its own dynamic. With every injury, anger and fear rises. Most people in Northern Ireland are totally opposed to the rioting, but sadly it does not need many to light the flame. The summer marching season will be a dangerous juncture.

This eruption has its causes, including the decision of the authorities not to prosecute the leader of Sinn Fein in Northern Ireland, Michelle O’Neill, for attending last June’s funeral of former IRA man Bobby Storey while breaking coronavirus disease restrictions. For unionists, that decision smacked of double standards.

Sectarian divisions are still stark and segregation is common. A staggering 97 percent of social housing in Belfast is segregated between Protestants and Catholics, while less than 8 percent of young people attend integrated schools. The impact of a rising Catholic population is also telling. Many believe that this year’s census will show that Catholics are now in the majority in Northern Ireland. This only serves to undermine the confidence of unionists, who feel threatened and abandoned.

Another factor is the lack of investment. West Belfast is one of Britain’s most-deprived areas. Children as young as 12 have been involved in the violence and even arrested. Youths in such areas have had nothing to do and also see little hope in the future.

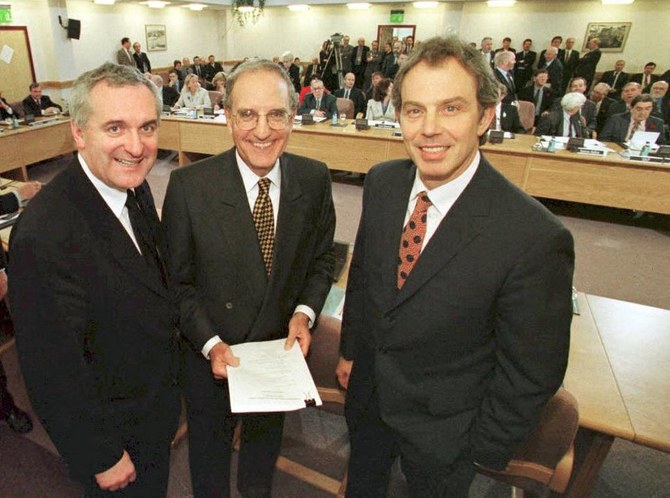

Saturday marked the 23rd anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement. This deal came about after the shedding of considerable amounts of blood, sweat and tears on the part of the negotiators and on the back of 35 years of sectarian violence, intercommunal tensions and terrorism, including on mainland Britain. Going back further, Ireland has endured conflict for centuries. Nobody should wish to see a return to the dark days of the Troubles. Just because peaceful relations have held, for the most part, since 1998 does not mean that all issues have been resolved, just as the formal end of the civil war in Lebanon did not equal perfect intercommunal bliss. One of the reasons peace took root in Europe after 1990 was the huge efforts to bridge the gaps between east and west, not least in the newly reunited Germany. Even here, however, leaders must be on their guard. Northern Ireland still requires similar efforts.

Just because peaceful relations have held, for the most part, since 1998 does not mean that all issues have been resolved.

Chris Doyle

The people of Northern Ireland do not take kindly to being treated as if the province is an inconvenient backwater. The English establishment in Westminster is doing exactly that. It took six days for UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson to say anything about the violence. Old Northern Ireland hands emphasize the need to work the phones overtime, reaching out to all parties at the highest levels. It is perhaps due to a failure of imagination that the Troubles could once again break out in Northern Ireland. Infamously, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has previously admitted to not even reading the Good Friday Agreement.

Brexit did no favors to Northern Ireland. Too many in the Brexiteer camp were reckless and too easily prepared to sacrifice peace in Northern Ireland for their cherished goals of what they believed to be a return of British sovereignty and independence. Northern Ireland, for some, was a burden. Former UK Prime Ministers John Major and Tony Blair, who were both involved in Northern Irish peace negotiations, warned back in 2016 that Brexit could lead to a resumption of violence.

Can the Good Friday Agreement survive all the contradictions of Brexit? The people of Northern Ireland want an open border with Ireland, but the British government refuses to concede one drop of sacred sovereignty in any deal with the EU. Unionists have noted the greater confidence Catholics have that there could be a united Ireland as a result of Brexit.

Johnson has made a series of contradictory promises, including telling loyalists there would be no border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland while also telling the world there would be no hard border on the island of Ireland. He ultimately agreed to a trade border in the Irish Sea. This means that British goods entering Northern Ireland are now subject to EU customs checks. Unionists see this as a betrayal and that Northern Ireland is no longer a fully signed up part of the United Kingdom. They want to see the border protocol ripped up. Jonathan Powell, the former chief British negotiator in Northern Ireland, wrote that unionist leaders “found it hard to believe that the British PM would have brazenly lied to them.”

The Irish government has sought to hold a summit, but this has reportedly been met with a cold shoulder from the British government, which is hyper-allergic to the merest suggestion that it is the Brexit deal and its stance on the Irish border issue that is at the root of the current flare-up in violence. London wants to avoid a summit that could descend into a cheap blame game. The unionists see any Irish government involvement as interference in the internal affairs of Northern Ireland. The British government is more than a little aware that US President Joe Biden, who is an ardent defender of the Good Friday Agreement, is paying close attention.

The events in Northern Ireland are worth watching and learning from. Too many conflicts are flourishing around the world and too many are on the brink of exploding. Northern Ireland is a salutary reminder why peace diplomacy is not a luxury but a necessity, and one that should not be abandoned when the ink on any deal is dry. Any peace agreement can break apart and, when it does so, it may take even longer to repair the damage.

• Chris Doyle is director of the London-based Council for Arab-British Understanding. Twitter: @Doylech

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Arab News" point-of-view