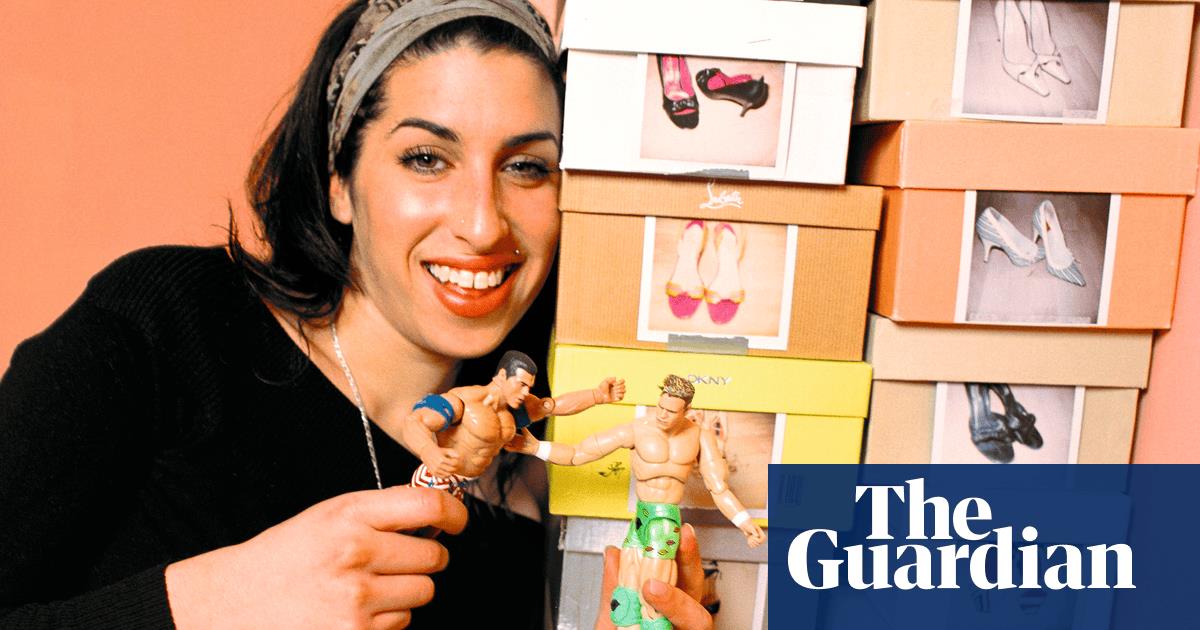

eleased when I was 14, Amy Winehouse’s debut album offered a bridge from the tween-pop I grew up on to an intriguing adult world rich with sophistication. Back then, I didn’t understand all the lyrics – who was “Badu”? What was a “Moschino bra”? – but that only added to the alluring sense that I was instantly cooler for listening. I spent many evenings in my bedroom trying to mimic Amy’s unfathomably syllable-packed rendition of Moody’s Mood for Love, or singing her ballads or fantastically cutting insults in the imagined direction of whoever was my romance of that week, depending on the drama.

By the time Back to Black arrived, I was 16 and a fully fledged Amy fan, sporting backcombed hair and thick black eyeliner. The album soundtracked my first proper heartbreak, comforting me during the brushing-teeth-while-crying phase with Love Is a Losing Game. It later uplifted me as I sauntered down the street with my head held high to Tears Dry on Their Own, wondering why on earth I did, indeed, “stress the man”.

I saw Amy play live just once, in Liverpool in June 2008. The Facebook photo album of the gig is titled “the best day of my life”, although I don’t remember leaving with the post-gig euphoria you get after seeing something soul-enriching. Of course it fell flat – she was very publicly struggling with addiction and an eating disorder. Her tiny shorts hung from her tiny legs. She looked like a shell of the Amy that was so full of life just a few years earlier. It was heartbreaking.

Even more heartbreaking was the way I watched her being treated by the media and the spiteful comments by people I knew. To those who didn’t love her and didn’t understand mental health problems, she seemed a spoilt brat who was wasting her talent. One particularly abhorrent column in the Sun said she should be dragged “by her egg-yellow hair round a ward at Great Ormond Street hospital and [shown] the children fighting to stay alive. To hammer into her thick skull that she’s lucky enough to have a healthy body and mind that she’s wilfully choosing to destroy.” Wilfully choosing to destroy? Healthy body and mind? The lack of sympathy she received for ill health that is clearly not a matter of choice still brings a red hot rage into my chest.

I learned of her death via a text message from my sister. I couldn’t believe it. It felt unreal, partly because she’d been turned into a caricature by the media by that point. Was the original Amy still there? How could she be gone? When trawling the news, trying to find answers to questions I couldn’t formulate, I found yet more vile commentary on her lifestyle and struggles – this time in the comment sections, now that the newspapers which had revelled in her downfall were falling over themselves to pay tribute. At the risk of exploding with rage, I wrote an article for my student paper questioning the mainstream narrative that surrounds those experiencing addiction and why some understanding for the condition and sympathy might be better placed instead.

As a fan, and someone who has also experienced mental ill health and lived the chaos that can bring, I felt I understood Amy and that she should be fiercely protected. She was a once-in-a-lifetime talent and a brilliant and vibrant personality who suffered no fools. She was also experiencing a number of mental illnesses that weren’t yet being widely discussed. When I saw Asif Kapadia’s Amy documentary, I couldn’t understand why she was still touring while clearly being too unwell to do so – why didn’t anyone she was working with pull the plug until she got better? I wrote an article asking what health support exists for musicians, which was the jumping off point for delving deeper into the subject when I found out what little help and understanding there was. Since that first article, I’ve often written about musicians and health, including a book, Sound Advice (co-authored with Lucy Heyman), which aims to help educate musicians and the industry about potential health issues in an attempt to aid prevention.

It’s hard to say whether Amy’s death shocked the music industry into understanding its obligation to protect artists. Seven years later, Swedish DJ Avicii took his life, having articulated his distress about the pressure of a heavy touring lifestyle. SoundCloud rapper Lil Peep died of a fatal fentanyl overdose. Demi Lovato narrowly escaped the same fate. However, I’m hopeful that things are changing for the better – I hear of major labels offering artists therapy and support programmes, while most young managers I speak to talk about the importance of protecting their artists’ mental and physical health. Musicians themselves are open about the pressures of being in the public eye and how it can exacerbate pre-existing mental health conditions.

Whether the toll of exposure – particularly for female musicians, treated as harshly as ever by the media – can be lessened with support is another question. To be a fan today is to understand the feeling I was left with on leaving Amy’s gig in 2008: that there’s a cost to this.