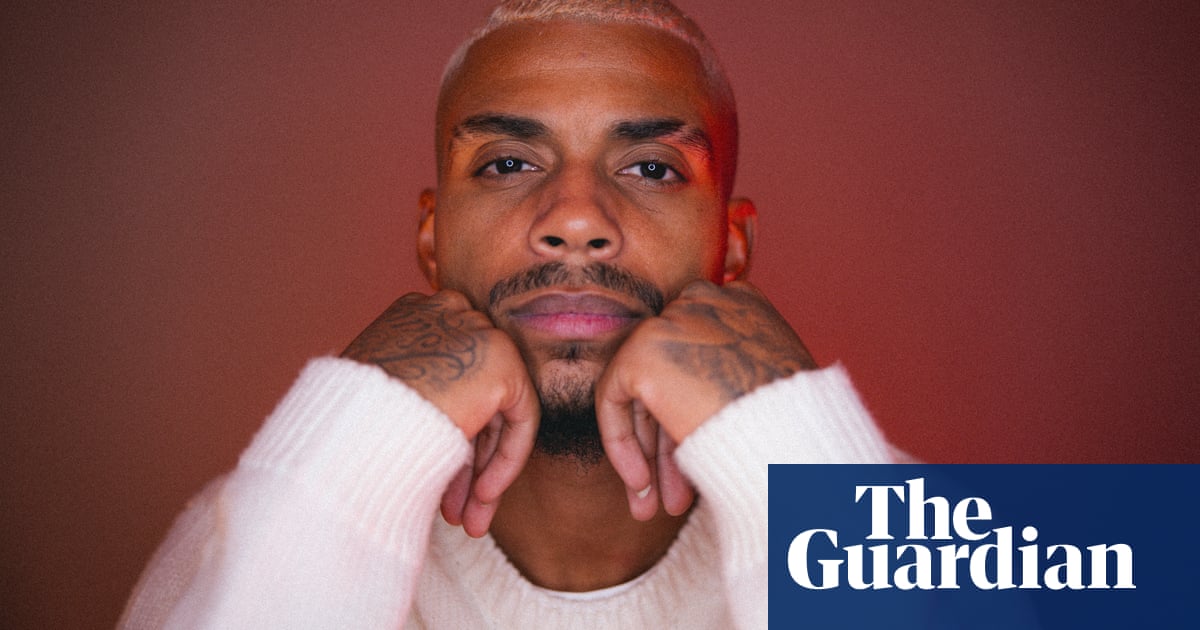

hen the actor Thandiwe Newton announced last week that she’d be reverting to the original spelling of her name, I felt some recognition. The journey her name has taken over three decades will strike a chord with many African and other non-western diasporas who have encountered the difficulty Anglophone countries have with accommodating foreign names.

While shooting Flirting (Newton’s first feature film) in 1991, the director decided to give her character her own name, Thandiwe. But in the film’s credits, Newton the actor was listed by her anglicised “nickname”, Thandie, to avoid confusion – this was done without consulting her. From then on she was known professionally as Thandie Newton.

Perhaps she knew the spelling and pronunciation of Thandiwe would be too troublesome for Hollywood. Perhaps Newton didn’t feel powerful enough to correct it. As a Black woman in an overwhelmingly white industry, it was her job to assimilate its standards.

In an interview for British Vogue, Newton has now declared of Thandiwe: “That’s my name. It’s always been my name. I’m taking back what’s mine.”

The name is native to the Nguni languages of southern Africa. In Zimbabwe, the native home of the actor’s mother, the language is called Ndebele – the second most spoken native language of the country after Shona.

My mother’s first name, Siphilisiwe, also comes from Ndebele. Her name slowly became truncated too. Growing up, I’d feel a little pang of pity or embarrassment hearing a British person trip over its meandering five syllables. People would constantly mispronounce it. Occasionally someone would combatively ask for it to be shortened – “I can’t say that, can I call you Penny instead?” – with an unthinking ease that showed little care for the importance people attach to their names, and their languages. Sometimes my mum would offer up a nickname: “Just call me Pillie,” she’d say, as a way to ease any sense of discomfort and for others’ convenience. Slowly, Pillie became her name – in her working life, with every letter that came through the door. Except when talking to close family and friends, Siphilisiwe ceased to be.

At school, non-western names can be a source of embarrassment for many. As a teen I’d wince when my surname, Kambasha, was called out in class. I’d watch other kids whisper butchered versions of it for comic effect at my expense. I think now of the infamous mid-2000s Celebrity Big Brother incident when the late Jade Goody referred to her housemate, the actress Shilpa Shetty, as “Shilpa Poppadom’’. Goody claimed she couldn’t say her name – though it was undoubtedly a cheap joke. This sort of thing is common and is seen by many merely as harmless fun, but it can have lasting impact. Juvenile prejudice and jokes can harden into discrimination in the workplace and beyond: studies show that having an ethnic-minority name in Britain can often be a barrier to getting a promotion, let alone a job interview.

Particularly in the past decade, and likely owing to an increased consciousness of our roots, there has been a concerted effort to encourage the appreciation of our unbutchered ethnic names. There is a greater, louder demand for westerners to respect these names in all their glory.

The Instagram account oruko.mi shares meanings behind Nigerian names while also highlighting people’s experiences with mainly western people mangling them. One user, whose name is Omotayo – meaning “a child of joy” – was nicknamed Toyota, but said that kind of ridicule “would not be their child’s narrative”. Thandiwe means loosely “you are loved”, and my own middle name, Thandekile, given to me informally by my grandmother, also comes from the same meaning. Siphilisiwe, my mum’s name, means “we have been given life”. It’s our job to ensure that these names continue unaltered, that their meanings remain and are protected.

Having names carelessly handled – even taken away from us – has an effect on one’s identity. It can feel like something is being slowly wiped away, leaving you feeling like a faded sketch of a person, not fully realised. And while amended names such as Thandie or Pillie allude to foreign origins, they don’t really belong in their native homes either. Such names, seemingly born out of a necessity for mutual understanding in one home, leave us feeling incomplete in our other home too. We are left stuck in the uncertain purgatory of the diaspora.

Thandekile doesn’t appear in any of my official documents. My first and middle names are western and my last is Shona, but I have always wanted something tangible to honour my Ndebele roots. My job is in the music industry: several years ago after working on the release of an album by the American band The War on Drugs, I received a gold record after hitting a sales milestone. I wanted my full name emblazoned on it: Michelle Anna-Maria Thandekile Kambasha. That disk is now hammered proudly to the wall of my parents’ living room in Harare. I can only imagine that when Thandiwe Newton first picked up a copy of Vogue this month, her name written across the cover in large letters, she felt a similar sense of pride – righting a wrong, defiantly reclaiming what was always hers.

Michelle Kambasha works in the music industry