haken, shoeless and with a gaping bullet wound to one of his feet, the young man staggered through Flávia Luciana’s front door at around 8am last Thursday as Rio’s decades-long drug conflict plumbed horrifying new depths.

“Help me! For the love of God! Help!” she remembers him pleading as he sought shelter inside.

It would be one of his last acts. About 30 minutes later, witnesses say a small group of police special forces appeared outside on Saint Manuel lane, a narrow alleyway at the heart of Jacarezinho, one of the city’s largest favelas.

Rifles raised, they advanced up two flights of stairs to Luciana’s door. One barged inside, pursuing the injured – and apparently unarmed man – into her nine-year-old daughter’s pink-walled bedroom, where a sign above the bed reads: “Here sleeps a princess.”

The girl’s father, André Franklin, remembers hearing one, possibly two shots as he and his petrified child fled downstairs onto a backstreet that would soon be strewn with bullet-riddled bodies and awash with blood. “Six [were killed] on this street: one in here and five in the house next door,” said Flávia Luciana, a 43-year-old food vendor.

Another 21 local men and one police officer, André Frias, would also die as security forces swarmed across the favela in the deadliest police raid in the history of one of the world’s most violent cities.

“They didn’t come to arrest anyone. They just came to kill,” said Norma Bastos, a local preacher as she roamed the community’s meandering back alleys, past bullet-pocked houses that paid testament to the intensity of the violence.

Leandro Souza, another community leader, said he had witnessed countless gunfights and police incursions during his 39 years of life in Jacarezinho, a vibrant but deprived sprawl of redbrick homes in north Rio. “But [this] was war, absolute war … human life was worth nothing here. It was a total massacre, a witch-hunt, a horror film I never thought I’d see in real life,” Souza said as stunned activists gathered at the favela’s samba school to contemplate the killings.

Rio’s favelas have suffered countless horrors since the drug conflict began to intensify in the mid-1980s and cocaine and war-grade weapons began flooding communities such as Jacarezinho, a longtime stronghold for the Red Command drug faction. Since then thousands of people – the majority young black men – have lost their lives to the relentless, corruption-fuelled skirmishes between police, drug traffickers and, increasingly, paramilitary gangs with ties to the state.

But never before have so many lives been lost in a single operation and the carnage in Jacarezinho – as well as suspicions that several victims were extrajudicially executed – has sparked a wave of protest and a political storm over the hardline tack Brazil has taken since Jair Bolsonaro became president in 2019.

Hundreds of demonstrators packed Jacarezinho’s main drag on Friday night to demand justice and heap scorn on the Brazilian president and his rightwing ally, the Rio governor, Cláudio Castro, on whose watch there has been an upsurge in deadly police incursions into the favelas despite a supreme court order to halt such operations during the Covid pandemic.

“The way I see things, this kind of operation only happens in these territories because they are majority black – and you can do whatever you want to a black body in this country,” said Joel Luiz Costa, a local lawyer and civil rights activist who helped organize the march.

Bolsonaro, a vocal supporter of police repression who has called for criminals to be shot “like cockroaches”, congratulated security forces for the raid and rebuffed growing outrage over the bloodshed. “By treating traffickers who steal, kill and destroy families as victims, the media and the left equate them with ordinary, honest citizens who respect laws and their neighbours,” Brazil’s pro-gun leader tweeted on Sunday.

“Crooks the lot of them,” Bolsonaro’s vice-president, Hamilton Mourão, said, without evidence, of the 27 people shot dead by police.

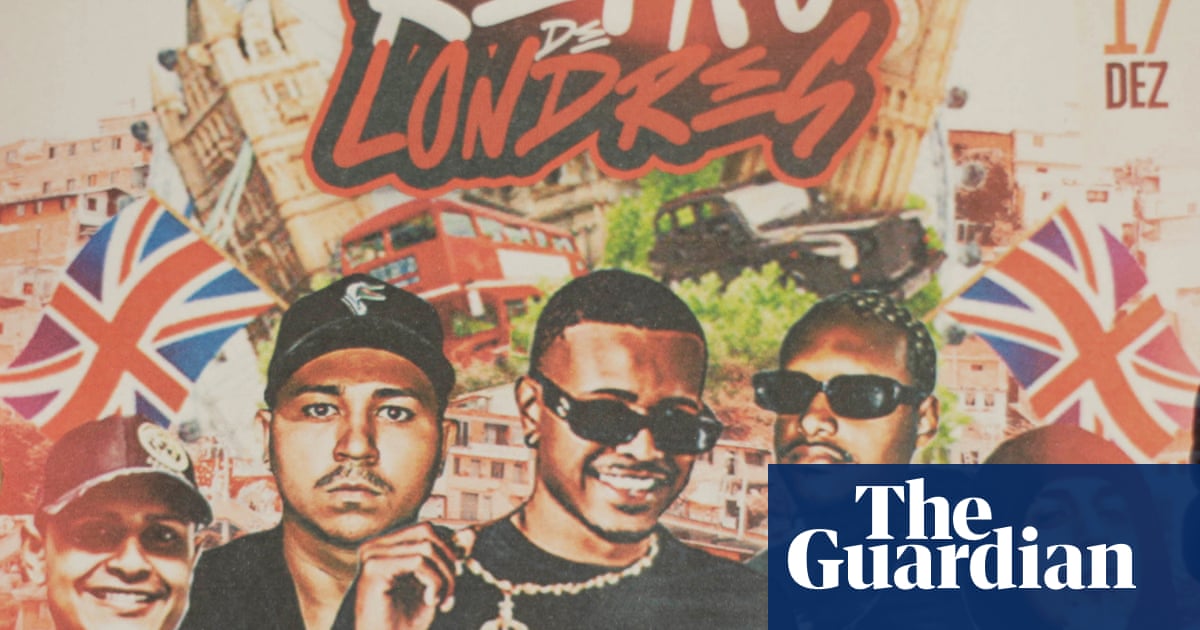

Many of the victims, men aged 18 to 43, do appear to have been involved in the drug trade, their nicknames spray-painted onto black plastic banners that now hang over Jacarezinho’s main streets. “Rest in peace, Jacaré family,” reads one tribute listing more than a dozen noms de guerre.

But others were not. As they laid Bruno Brasil to rest on Sunday afternoon, relatives insisted the 37-year-old odd-job man was not part of the drugs “movement” and had been shot in the belly by police while making an early morning trip to the shops.

“My brother was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” said his sister, Rafaela Lemos. “He was a worker. He wasn’t involved in anything at all … I can’t stay silent and let them dirty his name like this.”

Isaac Pinheiro de Oliveira, a 22-year-old who was also buried on Sunday, was a gang member and was known in the community as “Pé” or “Foot”.

“I won’t lie to you, he was involved in trafficking. But he wasn’t the kind of gangster who went around killing people,” his grandmother, Célia Regina Homem de Mello, said as dozens of mourners, among them Oliveira’s pregnant girlfriend, gathered inside a small chapel where his body lay in an open casket covered with white chrysanthemums.

Oliveira’s family claimed he and a friend – a fellow trafficker called Richard Gabriel da Silva Ferreira – had been summarily executed after police tracked them to a house just off one of Jacarezinho’s main avenues.

Oliveira’s aunt, Tatiane Teixeira, showed the Guardian a video she said he had sent her by WhatsApp at about 7am last Thursday in which he exhibits the bullet-wounds he sustained after being shot shortly after police began their pre-dawn raid. Teixeira claimed her nephew had managed to escape and hidden in a nearby house but was killed with Ferreira that afternoon after trying to surrender.

“They were executed. They weren’t armed. They could have taken them alive,” Teixeira claimed as she set off for his funeral from one of Jacarezinho’s barricaded entrances on Sunday.

“We’ve got to speak out, otherwise the same thing will happen in other favelas,” added Teixeira, whose son was also killed by police three years ago.

Thaciana Barbosa, 18, a close friend who was outside the house where police killed Oliveira and Ferreira, claimed: “They went in, told the residents to get out ... and killed the two of them in the sitting room in cold blood … I heard the shots. It was horrible.”

Authorities have rejected accusations of extrajudicial killings during the Jacarezinho incursion, during which more than 20 guns were seized and six suspects arrested. “The only execution … was of the civil police officer who was shot in the head after getting out of his bulletproof vehicle … All of the others died in combat, and those who preferred to surrender were arrested,” the senior police official Rodrigo Oliveira told CNN Brasil.

As hundreds of officers gathered at the funeral of the slain drug squad agent on Friday, Allan Turnowski, police chief, praised his agents’ “maturity and professionalism” in the face of heavily armed criminals who were shooting to kill.

But as more gruesome details emerge from Jacarezinho residents and relatives, there are growing calls for an inquiry into an operation one Brazilian newspaper said exposed “the stupidity of the war on drugs”.

On Friday the UN human rights office urged “an independent, thorough and impartial investigation” and the Brazilian supreme court judge Edson Fachin said there were signs “arbitrary executions” had been committed.

Costa, the activist, said it was impossible to know exactly what had motivated the bloodletting, which claimed even more lives than the notorious 1993 massacre in a nearby favela called Vigário Geral. But like many, he suspected the shooting of a police officer in the early stages of Thursday’s raid had sparked “a revenge operation” as enraged operatives rampaged across the favela in retaliation.

Others wonder if the assault on one of the Red Command’s most important bastions might be part of ongoing efforts to weaken Rio’s oldest drug faction and help paramilitary groups – often made up of off-duty and retired police officers – expand their presence across a city they now control more than half of.

Oliveira’s grandmother said she felt for the family of the dead officer: “But they went in there to kill. They didn’t go there to make arrests.”

The 78-year-old said she had spoken to her grandson in the hours before his death after he called her from the house where he had taken refuge from police.

“Don’t worry, Grandma, I’m going to get out [of the gang],” she remembered Oliveira insisting before police stormed the building and ended his life.

“I’m just one more Brazilian woman who has lost her grandson in this way,” De Mello lamented before he was entombed in a cemetery already packed with the young victims of Rio’s interminable conflict. “They could have put him in prison,” she added. “Brazil needs to change.”