vintage Pathé newsreel from 1936 is playing on a loop at the Whitechapel Gallery with a commentary so comically steeped in archaic sexism, the “jokes” are hard to decipher. It’s a light item about an artist called Eileen Agar, who has made herself a hat covered in fake seafood, in which she is filmed walking along a London street while people stop and stare, amazed.

It says as much about Britain before the second world war as it does about Agar, whose artistic life the Whitechapel has been reclaimed in a copious exhibition. This was a society in which wearing a mildly eccentric hat was considered outrageous enough to get you on the news. The people who gasp at Agar seem to belong to an ordered, rule-bound Britain that’s hard to imagine now. It’s not the past we’ve been watching in The Pursuit of Love – this actual footage from the 1930s reveals an age too drab to inspire nostalgia.

I almost wish the Whitechapel had taken a cue from television drama and given us a fictional, cocktail-sipping Eileen Agar, throwing madcap ideas around while she helps Poirot solve a murder at the Mitfords’ mansion. This British surrealist did have some commendably wild notions. Her most famous was to cover a plaster head in silk scarves, feathers, sea shells and giraffe hide to create her celebrated image of dream and desire, Angel of Anarchy. But this show reveals that anarchy in the 1930s UK was a very modest revolt.

Agar belonged to an avant garde that tried to bring radical ideas from the continent to a smog-darkened, Depression-crushed Blighty. Surrealism started in Paris in the 1920s when poets led by André Breton sought to sidestep the dullness of the conscious mind. It became a revolutionary assault on bourgeois logic in the art of Max Ernst, André Masson and Joan Miró. Then it finally reached Britain when Salvador Dalí nearly suffocated in a deep-sea diving suit at London’s International Exhibition of Surrealism in 1936. Agar’s fishy hat, which she called Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse, was her own response to this subversive invasion.

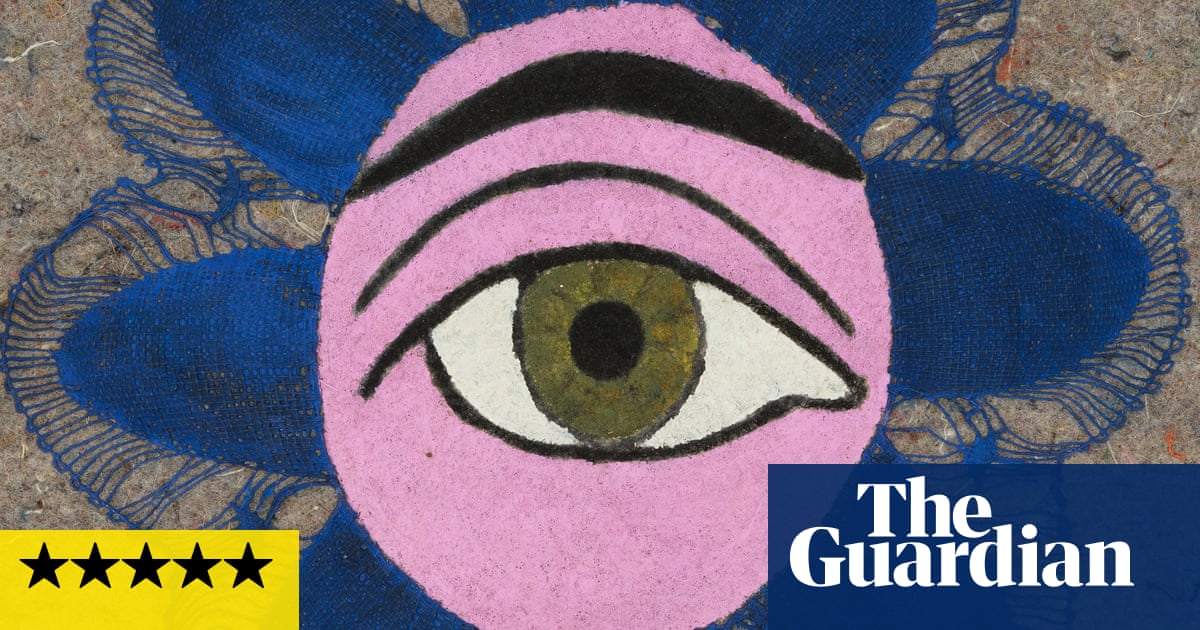

She showed in the exhibition, joined the Surrealist Group and made even more fishy art. The windswept beaches of this sceptred isle fascinated Agar. The most memorable things on this exhibition are her seashore assemblages. Her 1939 work Marine Object is a salty evocation of things changed and transformed by the sea. In the barnacle-covered, broken-off neck of an ancient Roman amphora lodge a starfish and other fantastical flotsam.

Yet Agar’s fish’n’chips surrealism is more Shakespeare than Breton, celebrating sea changes that make everything rich and strange. She clearly wasn’t too fixated on the arcane theories of French thinkers trying to synthesise Freud and Marx. Her found images of mystery and transformation have more in common with Powell and Pressburger, or Jean Cocteau – an art of dreams without the Freudian baggage. Corals and shellfish are arranged in dreamlike boxes, and small sculptures made of shells and pebbles draw attention to the surreal shapes that nature itself creates. Her eye for the bizarre merges with a romantic feel for wonders of landscape in black and white photographs of shells, rocks and driftwood. She was one of the first British artists to see the power of found stuff. Her marine collections anticipate Damien Hirst.

Yet it’s not exactly menacing. This domesticated British version of a revolutionary art comes with all danger eroded. Photos of rocks don’t really rival the razor slicing an eyeball in Un Chien Andalou. Instead, there are photos of Agar on the beach with Picasso. There’s a sense, as with other British surrealists such as her friend Roland Penrose, of being a dilettante fellow traveller.

That’s not the problem with the exhibition. The curators have worked hard – too hard. They’ve searched for forgotten canvases by Agar in the attics of art history to build a comprehensive survey of her career, when a show focused on her surrealism would have been much more fun. It turns out her dreamy seashell creations were just a phase. She started out as a painter and ended up a painter – continuing into the 1980s, and dying in 1991. So we get what feels like every painting she ever made, from a 1927 Self-Portrait in a Cézannesque style to a portrait of Dylan Thomas. There are portraits of her lovers by the seaside (where else?) and some very unconvincing “cubist” art. It’s hard to know why we are supposed to care.

Agar’s brilliance was as a weaver of dreams from found stuff, a Miranda of the surrealist seashore. Her freshness is choked by this overstuffed trawling net, and what’s genuinely important about her gets lost in the heap. There’s a bit of a stench on the quayside.