he pandemic, we often hear, is forcing a rethink in economics. We are leaving behind one model: the austerity-obsessed small state that outsources the job of macroeconomic stability to unelected central banks. Central banks, in turn, worked to target inflation under a regime of benign neglect for unemployment; it was assumed, meanwhile, that the bond market should and would discipline governments into fiscal rectitude.

Now, the Biden administration’s “once in a generation” spending plans suggest a paradigm shift is under way. It puts governments, through fiscal policy (taxing and spending), back in the driving seat. In this sense, macroeconomics has the potential to become more democratic. But are we celebrating too soon? The big test of the paradigm shift, possibly the fundamental test, is how we go about decarbonising our economies.

There are two ways to organise the low-carbon transition: through the state itself or through the financial sector. What might be termed the “big green state” approach involves massive public investments in green infrastructure and industries. When private finance recently lamented Biden’s infrastructure plans, it was objecting to a big-state route to decarbonisation that rejects the rhetoric of public-private partnerships.

Indeed, the “big finance” approach wants the state – through its fiscal and central bank arms – to simply guide the private sector by changing price signals. In this scenario, the state plays a smaller role, making carbon expensive by forcing companies to pay for polluting. For instance, Germany recently introduced a €25 (£21) tax per tonne of carbon emissions on petrol, diesel, heating oil and gas. Higher carbon prices, the wisdom goes, will incentivise producers and consumers to transition to green energy. Private finance is there to lend the money that this transition requires.

The numbers behind private green investment seem to add up: there is now $30tn (£21tn) in ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) assets. The green “rush” is expected to accelerate as central banks move to decarbonise their operations and reduce subsidies to carbon-intensive activities. Take the Bank of England’s plans: under its new environmental mandate, it argues that the transition to net zero must be largely financed by private finance (as opposed to the state), in an orderly fashion that requires central banks to subsidise green and only “escalate” to penalising carbon financiers if, over time, companies fail to meet commitments towards decarbonisation.

The strategy of cuddling carbon financiers is at the heart of the Cop26 conference that takes place this year in Glasgow. The hot new private sector gig for high-level public employees is green finance. But the world of “green finance” has injustice and inequality built in. It reduces democratic government action to higher carbon taxes, which often place the burden of decarbonisation on the poor. Government spending is to be directed to “derisking” private infrastructure, to cover the gap between the fees paid by users of essential public services and the commercial rates of return expected by private investors.

Yet having privatised public services while hiking carbon taxes on ordinary people threatens a political backlash, which will reduce politicians’ appetite for meaningful decarbonisation measures. It will also reinforce the pressures to trust global asset managers to set the pace of green investment, even though the financiers’ “environmental, social and governance” (ESG) rush is rife with greenwashing: PR exercises that stick green labels on high-carbon activities. This greenwashing is a feature, not a bug, of big finance-led decarbonisation. It allows private finance to both enjoy the green subsidies promised by central banks and to protect profits from democratic forces that may, one day, transition from cuddling to penalising carbon financiers.

The big finance approach owes its political appeal to fiscal fundamentalists who point to Covid-19-related surges in public debt to argue that the state simply cannot afford to green the economy. Instead, financiers dangle trillions of ESG investments in front of politicians, seducing them into believing the market will take care of the climate crisis. This validates unambitious carbon politics, as we see all too clearly in the EU’s sustainable finance initiative, which created a green public standards system. Four years after it was launched, this classification system for “sustainable” activity is now under serious threat of greenwashing from member states that want to include natural gas and other dirty activities within its scope. In turn, European commitments to develop in parallel a system that works towards penalising dirty lending have evaporated.

Surrendering to vested carbon interests is easier when politicians cannot rely on a plausible green macroeconomic paradigm; instead they are still confronted, on a daily basis, with threats that inflation-concerned central banks will withdraw their protective hand from government bond markets. Indeed, central banks worried about the inflationary pressures triggered by economies reopening are now furiously debating how quickly to allow borrowing costs to rise.

Climate activists should be prepared to fight the battle against fiscal fundamentalists with a simple message: the government is not a household. It has central banks on its side, and if there is a macroeconomic lesson the pandemic has taught us, it is that central banks can do a lot. In high-income countries, central banks have bought almost all debt issued by governments in 2020. They can and should continue to work closely with governments to accelerate decarbonisation. We cannot rely on private finance to lead us out of a climate crisis it has systematically contributed to. We have to disempower carbon financiers, and we do that by making the democratic state – not investors – lead the way forward.

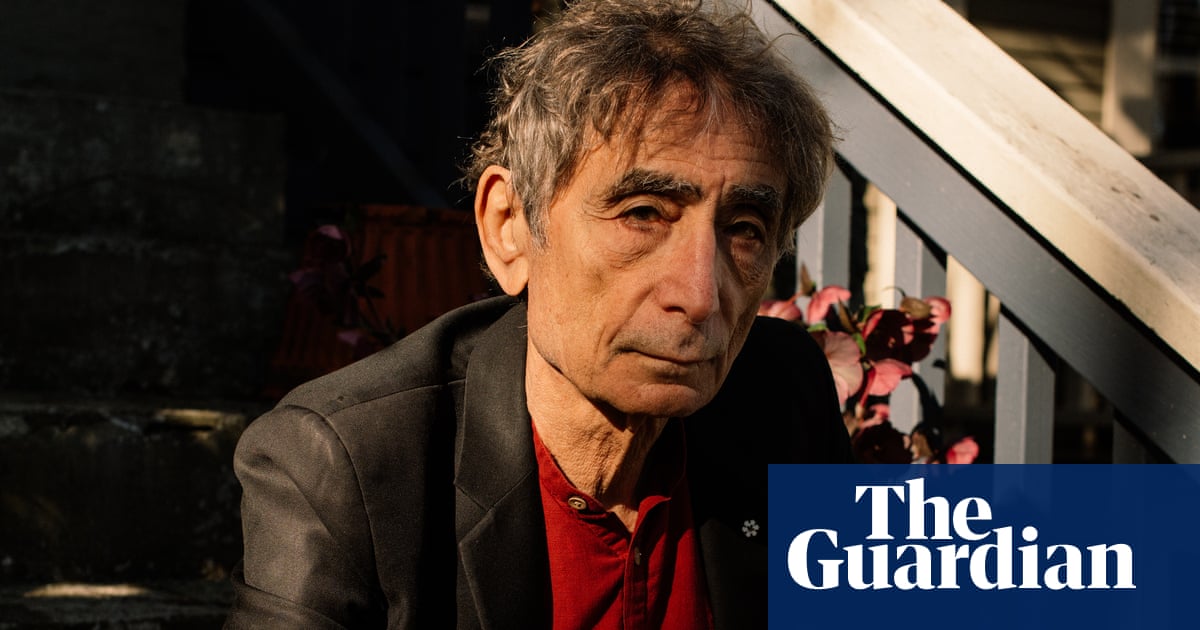

Daniela Gabor is professor of economics and macrofinance at UWE Bristol