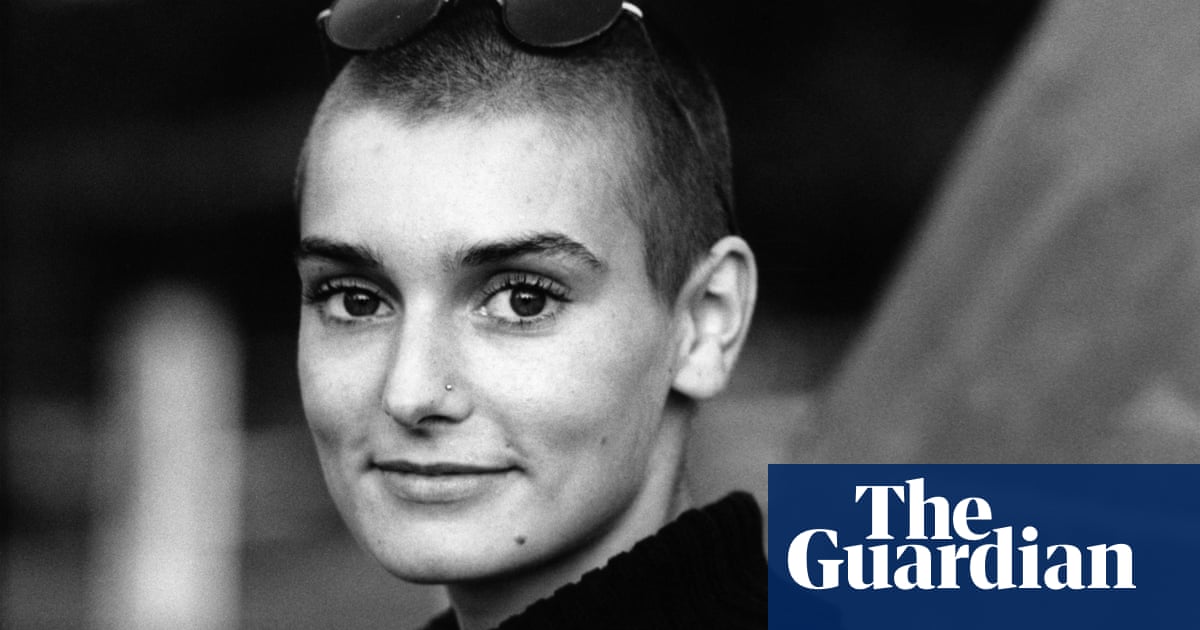

elebrity memoirs often come with a ghost writer. There isn’t one here – there are only ghosts, the ones the young Sinéad O’Connor hears in the piano at her grandmother’s house and the others with which she has wrestled for a lifetime. No matter how public her business, or how much people think they know about the Irish singer’s triumphs and travails, this is an artist who never ceases to surprise.

O’Connor has spent her career, it seems, coping with the after-effects of childhood trauma and then another lifetime coping with more trauma piled atop it – fame, infamy, pariah status, a 2015 hysterectomy, a questionable 2017 US TV interview. You’d be forgiven for thinking that O’Connor might require not just a ghost writer but a nurse and maybe even an imam on call (she converted to Islam in 2018).

She doesn’t. Speaking for herself is something primal for this artist. The 11-year-old O’Connor was hit on the head by a train door and has since been diagnosed with complex PTSD and borderline personality disorder, but her words read lucidly, righteously, quite reasonably, even when she describes the holy spirit appearing to her as she lies on the floor, taking a violent beating from her mother.

O’Connor also doesn’t need a ghost writer because she has, throughout all of it, rarely been at a loss for what to say. It’s just that those words have often not been enough to save her or that they have been disbelieved. In 1992, O’Connor told the public something it could not cope with hearing: she tore up a picture of the pope on Saturday Night Live to protest about sexual abuse within the Catholic church. The act cut her career off in its prime. She was vilified. History proved her right. “Some things are worth being a pariah for,” she notes.

Playing the shaven-haired Cassandra, she says now, allowed her to escape stardom, ironically enough. O’Connor felt she was a punk, not a pop star; she dyed the Public Enemy target logo on to her hair at the 1989 Grammy awards out of solidarity with the hip-hop acts who were too incendiary – too black – for mainstream awards support.

She never lacked words – or courage, it seems. O’Connor recalls as a young girl begging a priest at Lourdes to take her mother in hand (he couldn’t). Back home in Ireland, she asks her mother’s doctor to intervene (he does, but the relief is only temporary). Until her mother’s death when O’Connor was 18, the singer remained torn between this loyalty and her self-preservation.

One might call this jaw-dropping book a misery memoir of sorts, but it is one like few others. Bob Dylan, Prince, Lou Reed, Muhammad Ali and Janet Street-Porter are just a few of the luminaries strobing through its pages. The difficult Reed turns out to be a gentleman, while Prince comes out of this account very badly.

He summons O’Connor to his mansion where he tries to bully her, hits her with something heavy inside a pillowcase and pursues her when she runs away. Nothing to do with Nothing Compares 2 U, the Prince cover that shot O’Connor to mega-stardom – this was seemingly revenge on O’Connor’s then-manager, Steve Fargnoli, who had previously handled Prince’s affairs.

As Bob Geldof noted in a recent interview, only Sinéad O’Connor could have had the strength of character to bear being Sinéad O’Connor. Rememberings retells her painful childhood in episodic vignettes, segueing into scenes from a fast-rising music career. All of this is dealt with candidly and, when the occasion calls for it, caustically. The anecdotes are gold. Rastafarians feature heavily, alongside a fair few nuns and rabbis, all counterbalancing the many notches on O’Connor’s bedpost, although you do wish she was a little less fond of transcribing patois. It’s always great when she puts on a wig to go incognito – once, at the height of the post-SNL furore, she attends a protest against herself. Years later, O’Connor disguises herself again to catch a man trying to sell a compromising photo to the Irish press.

But it is an incomplete account, some of it written before 2015, when O’Connor’s hysterectomy spiralled her into crisis, and some after, plus a section annotating her albums to date. All the weed she smoked over the years has blunted her memory, O’Connor says. Her powers of recall are also still recovering after the radical hysterectomy, the mental health crisis it precipitated and the very public breakdown that followed in 2017.

A US TV psychologist known as Dr Phil offered to pay for O’Connor’s therapy in exchange for an interview. As O’Connor tells it in an explanatory chapter, both the interview and the type of therapy proved ill-judged and re-traumatising.

The road back from all this has been long – she credits the staff at St Patrick’s University hospital, Dublin, with her recovery. But O’Connor is powering up again: another album is in the pipeline. The years have been kind to O’Connor’s voice, which remains a thing of wonder. Given everything, it is perhaps no coincidence that her music has always had an edge to it – a kind of barely perceptible vibration – that all the pillowy production techniques of the era couldn’t douse, a zealous sense of purpose and a ring of emotional truth.

Rememberings by Sinead O’Connor is published by Sandycove. To support the Guardian order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply