ast week, I made a trip into central London, and spent the day gloriously, nosily, watching strangers. In no particular order, here are some of the things I observed. A sartorially bold man in a matching print shirt and face mask. Three women walking abreast, refusing to yield the pavement to anyone. Four teenagers shouting out rap lyrics on the underground concourse. As they walked past, an elderly man flinched and clutched his belongings. They’re not dangerous, I wanted to reassure him. Annoying, yes, and very bad rappers, but not dangerous.

I’ve missed traditional people-watching during the lockdown. Of course, we all watched people from our windows. The delivery drivers who always seemed to go to the wrong address. The mothers (and it was mostly mothers in my neighbourhood) on their school runs, herding children to the school gates. And of course, the righteous runners, cyclists and power walkers, refusing to let a global pandemic stand in the way of their fitness goals.

Yes, we still watched strangers from behind our blinds but it wasn’t the same. First, there is something voyeuristic about watching someone when they can’t watch you back. If they could see you watching, they probably wouldn’t be picking their nose.

Then there’s the imbalance of power, the invasion of privacy and the negative connotations that go with curtain-twitching. In television dramas, curtain-twitchers are often lonely, bitter people who have nothing better to do than watch other people living their lives and call the police if they look like they’re having fun.

But people-watching, now that is a celebrated art, because both the watcher and the viewed are on a level playing field. I can look at you and you can look back. People-watching is egalitarian, democratic and probably good for the environment because instead of running down your phone battery for diversion, you’re using your eyes. And most interestingly perhaps, there is the serendipity that can happen when the glances of two strangers meet.

I was on the tube once, when I just happened to look at a man at exactly the same moment he looked at me. He was nicely dressed and seemed tall, even though he was sitting down and so I couldn’t say for sure. All the way to my stop, we kept glancing at each other and glancing away. I got off at King’s Cross and thought to myself, “Well, that was that.”

As the doors beeped and slid shut, the strange man leaped out of the tube carriage and landed on the platform beside me.

“I noticed you were looking at me. Can I have your number? Would you like to go out sometime?”

He was slightly out of breath from his long jumping feat. I studied this complete and total stranger. No dating algorithm would have led us to cross paths. It was unlikely that we knew a single person in common. And yet, here we were, opposite each other on an underground platform because our eyes had met.

“No thank you,” I said and walked away.

If I’m honest, he wasn’t really my type. Nothing came of our encounter, but something could have. We might be married now and have four children and it would all have begun with “watching you, watching me”.

The pandemic has left its sticky fingerprints on everything. How we work, how we socialise and, sadly, how we people-watch. In the past, people-watching was often driven by curiosity, but now there is an element of policing that has come into global people-watching norms.

These days, there is a distinctly passive-aggressive undertone to the people-watching on public transport. Are you wearing your mask properly? Is it covering your nose? Are your nostrils visible or, worst of all misdemeanours, have you turned your mask into a chin strap? Yes, we’ve heard that there are some people that are exempt from wearing face masks, but nobody ever seems to quite believe that the maskless specimen in front of them is one of these rare people. I must confess, I have moved down the carriage because I was sitting next to a maskless person who also happened to be coughing into their hands.

Is people-watching rude? It depends on your technique. If you’ve ever been asked by a stranger, “What are you looking at?” then you’re probably doing it wrong. You’ve gone from people-watching to people-staring. The art is in the subtlety and brevity of the look. I suggest practising in front of the mirror or with close friends and family.

As a writer always on the hunt for characters to populate my fictional worlds, people-watching has proved invaluable. I love to read the new wave of auto-fiction, where authors draw from their experiences and write novels that are almost indistinguishable from their lives. But what if your life, like mine, consists mostly of, “woke up, went to Tesco, did some writing, went to bed”? Even the most talented of auto-fiction writers might struggle with such material. So to any writers just starting out, I recommend people-watching to add some sauce to your fiction. Also, if your characters are inspired by strangers, they can’t sue.

I’m glad the world has opened up and I can once again watch strangers in real life, instead of watching them mostly through my window and on social media. Strangers on social media are perfect, photogenic and are always standing in the sunlight. Strangers in real life are like you and me: normal people. So if you catch me watching you in public, watch back. Who knows what might happen next?

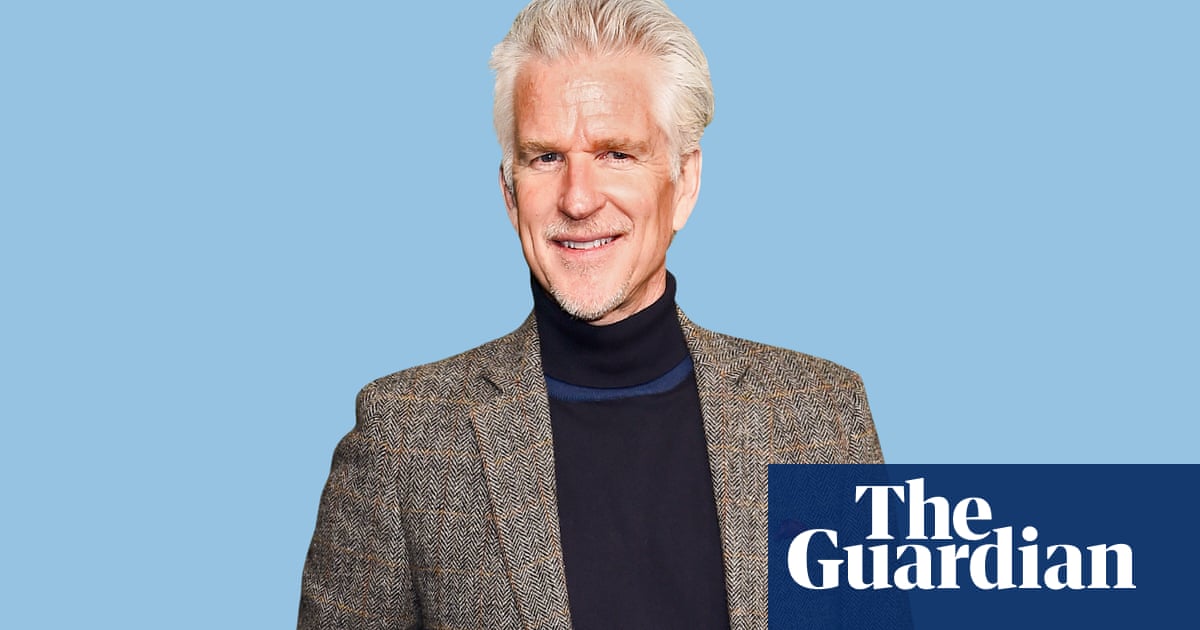

Chibundu Onuzo is the author of Welcome to Lagos. Her latest novel, Sankofa, was published this month