Not since criminals were barred from profiting in this way can a publisher’s announcement of a memoir have united the British press in such disgust. Before that, even the gangster turned memoirist, “Mad” Frankie Fraser, was not, in his literary pomp, faulted for bringing shame upon his family. If, as a torturer for the Krays, Mr Fraser pulled out his victims’ teeth with pliers, well, he never came close to embarrassing the Queen – and doing so, yet more barbarously, in a jubilee year.

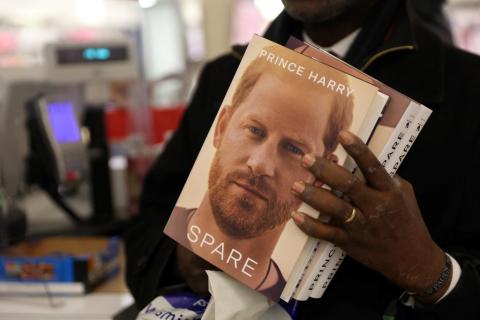

Nothing, for the royal-watching guild, not even its professional interest in the benefits, can excuse Prince Harry’s decision to publish, with the help of an award-winning US author JR Moehringer, an “intimate and heartfelt” memoir. Defenders of cancel culture might, in fact, want to welcome this overdue acknowledgment from traditional media adversaries that free speech must have its limits. Unseen, the book has been damned as self-indulgent, superfluous, greedy, hurtful, biased, perfidious, overprivileged, hypocritical and premature. Did the 36-year-old émigré not check the UK guidelines for memoir writing? Who did he think he was – Malala?

One biographer, the author of the 2018 title, Harry (“delves into his troubled childhood and the lasting effect of losing his adored mother”), has heard the prince’s version will probably delve, competitively, into the same lasting effect. “It was a terrible tragedy,” Angela Levin allows, on Twitter, “but sad the man can’t move on”. The only people entitled to make money from Prince Harry’s interesting story are, you gather, people who are not Prince Harry.

It has been further explained that what may have been acceptable from Harry’s parents in, on one side, a faithfully whiny official account and, on the other, a sensationally damaging attack on Charles and his family should be denied their younger son. The “disrespectful” jubilee timing offends, though not as much as his alleged inconsistency in believing, presumably uniquely, that memoir-publishing is compatible with the right to privacy. Queen Victoria’s Leaves From the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands doesn’t count, being forgotten. The Daily Mail notes approvingly that Edward VIII “waited 15 years” before publishing his effort, possibly the first sign since his abdication that the unlamented Nazi sympathiser could yet prove a useful role-model. In contrast, it’s the Sussexes who remind Piers Morgan of “Kim Jong-un with a dash of Vladimir Putin”; that’s when they are not designated, by the same expert, “Prince Poison and Princess Pinocchio”.

Will it be any consolation or only make it worse if, given the inspired-looking choice of ghostwriter, this turns out to be the best memoir yet produced by a British royal? What if, yet more painfully, it turns out to be as impressive as Open , the autobiography Moehringer wrote with Andre Agassi, and as engaging as his own memoir, The Tender Bar? Not that it should be hard to improve on a fawning Dimbleby, but surely the hardest news for UK critics is that his American collaborator should appear so perfectly qualified to do something compelling with the story of an anxious boy trying to negotiate, then, as an unhappy young man, to break away from a generationally messed-up family. And it can only help, when it comes to Harry’s tricky Bouji period, and enduring enthusiasm for banter, that his ghostwriter, while being raised by a loving, hard-up single mother (who “would insist that we take regular mental health breaks”) and neglected by a cold father (“an unstable mix of charm and rage”) sought out the warmth, endless chat, jokes and booze inside the bar of the title. The prodigious if sometimes lethal contribution of continual inebriation to male socialising anticipates, in Moehringer’s memoir, its recent, alluring role in Thomas Vinterberg’s film, Another Round. “With the first taste of cold beer and Bloody Marys the men began to behave differently. Their limbs seemed looser, their laughter more lively…”

Prominent among last week’s anonymous insults was the prediction that Harry’s memoir would really, befitting a new understanding of the military hero as pathetically emasculated, be “written by Meghan”. If so, hiring the Pulitzer-winning Moehringer, who has been admired for his insights on masculinity and male friendship, seems a complicated and expensive way of going about it. Though he does, in The Tender Bar, conclude: “Every virtue I associated with manhood – toughness, persistence, determination, reliability, honesty, integrity, guts – my mother exemplified.” Also likely to be frustrated, given Moehringer’s personal alertness to complacent privilege, are expectations that Harry, who recently complained of being “cut off financially”, will be unable entirely to suppress his inner Etonian. “I watched my schoolmates arrive,” Moehringer recalls, of his first day at Yale, “a flotilla of families sailing with the wind up College Street, in cars that cost three times what my mother earned in one year”.

A poll indicating limited interest in the book has been received triumphantly by anti-memoirists. But if Moehringer repeats his achievement in Open, of making fan-level detail fascinating to the previously indifferent, Harry’s story could engage an audience left cold until now by routine royal hagiography. When has it ever had jokes? As for the timing, it could hardly be better than as soon as possible, when this “wholly honest” book canilluminate the process whereby Prince George, costumed and on display aged eight, is being trained on behalf of a usually grooming-averse nation to accept his destiny. That is, he’s next to be, as Harry has put it, “trapped” within the family that willingly harbours Uncle Andrew; next to never leave home, instead becoming decreasingly equipped, like some pedigree animal, to survive in the outside world.

Even if Harry has, in the unforgiving estimation of our royal authorities, come closer to regicide than the unhygienic Boris Johnson, his account – or the one JR Moehringer is writing – could yet take its place among the classics of cult survival.