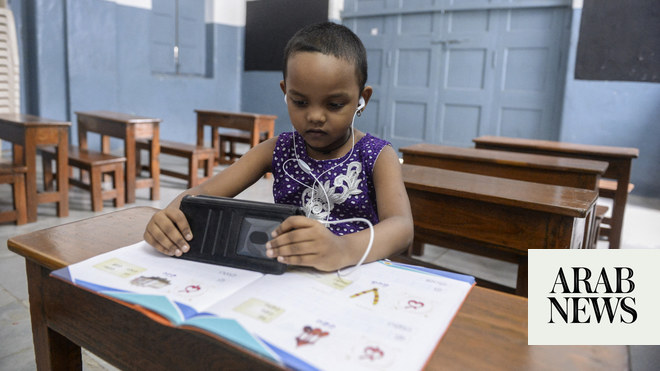

To many readers of these lines, playing a musical instrument may be a given, something they grew up with and may have been forced to learn for a year or two in childhood. But to many children in the Middle East, learning to play a musical instrument is a dream. This should not be the case anywhere in the world, but especially not for the children of this region.

Most people can remember at least one moment in which they heard a song, a recitation, a piece of music, or a simple bit of melody that resonated with them in a deep, emotional experience. A flood of feelings can be brought about by a lullaby from distant childhood, a song from a meaningful stage of life or a chant from a particularly significant religious ceremony. Some may be good and welcome, others perhaps less so. But the experience is there. Even people with hearing difficulties speak of such experiences and recollections. Common occurrences such as these have made the power of music hard to dispute.

Admitting to the power of music is certainly the case for people who accept music as a positive addition to human life. It is even more so for people who think rather suspiciously of music and its influence on the human psyche. The affective power of music not only has an emotional impact on us, it can also be effective because music can influence patterns of thought and behavior, so much so that it has long been used as a tool for mass mobilization.

Thanks to its power, music has been part of education for a very long time. In ancient Greece, music was one of the four pillars of the scientific program of education known as the “quadrivium” (along with astronomy, geometry and arithmetic). It was also viewed as an element in building the moral character of pupils. But it took many hundreds of years before the scientific understanding of music in Europe started accounting for its emotional value.

In the Middle East, however, the inner workings of music were always part of the picture. In the spiritual sense, music is known to have been considered an enhancing factor, especially in helping the devout to memorize sacred texts. Examples abound in texts and practices from all three major religions of the region. Accepting and benefiting from the affective power of music are integral to the history of the region and its cultures.

The word “music” here has a figurative meaning: An encompassing sense that no single word could satisfy. The various ways in which people experience, understand and make this thing we often call music require an encompassing meaning beyond ready terms and the differing values they conjure up. Music in this figurative sense is a concept rather than a thing. What is more, it is a concept that is ubiquitous, if contentious. It is with this sense that I hope we can move beyond a view of music as an inherently negative thing, which has prevented it from being taught in many parts of the Middle East.

Accepting and benefiting from the affective power of music are integral to the history of the region and its cultures.

Tala Jarjour

People often draw the line on the admissibility of music along the use of instruments, thus distinguishing between vocal recitation and instrumental music. Others may draw the line along certain rules of pitch organization. But no matter where such a line is drawn, it remains artificial. That is especially the case in the Middle East, where the line between various forms of voiced performance and instrumentalized song is hardly perceivable. Think of ancient poetry or of various forms of long, sung poems, most genres of which are thought to have been improvised and were present in many languages of the region.

A good example that remains in living practice today is Bedouin poetry. When performing, the reciter (usually male, when in public) accompanies his voice with that of the rababa, a single-stringed bowed instrument known in various forms throughout the wider Middle East and the Muslim world. It would be difficult to separate the two voices in this case. It would also be difficult to try and draw a line between what is and what is not music, for the purpose of dismissing one and accepting the other.

The point I am trying to make is this: The need for intoning the human voice, the curiosity about human-made sound by mechanical means, and the impulse to try them together are human activities that have been known to accompany our lives and interactions for a very long time. Just think of the most instinctive and basic form of human communication, that between a mother and her newborn. With or without language, the (mother’s) human voice and its inflections are present, and are never without intonation or differences of tone and volume. It is not only mothers that have this instinctive form of voicing; most people (except those who worry about sounding silly), when speaking to babies, communicate through affective sounds, which also happen to be quite effective in this case.

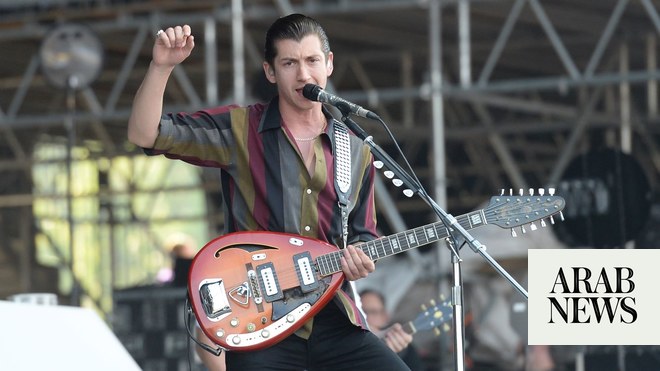

Whether we call it music or not, at the end of the day we humans are musical creatures and that is simply how our brains are wired. Making pleasing sounds and using them to communicate with each other, with what we believe is beyond us, and with our inner selves is an activity that comes to us naturally. Learning how to practice it in ways that are consistent with our sophisticated brains and our stunning ability to master fine motor skills is a beautiful way of living a fuller life.

Investing in a more diverse and continuously evolving music education in the region, especially for children, is a very good strategy to enhance the quality of life in countries of the Middle East — especially if the people in charge uphold the cultural legacy of their musical ancestry.

• Tala Jarjour is author of “Sense and Sadness: Syriac Chant in Aleppo.” She is visiting research fellow at King’s College London and associate fellow at the Yale College.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by writers in this section are their own and do not necessarily reflect Arab News" point-of-view