Avision of cherry blossom, pink and white against blazing cobalt skies, runs floor to ceiling all through the entrance corridor to this show. The sight dazzles and bewilders, releasing afterimages that dance around the viewer with every step. The effect is hyperreal – and conspicuously achieved through digital photography – yet the experience feels both entirely timeless and completely Japanese. You could be walking through the blossom to some ancient Shinto temple.

Mika Ninagawa (born 1972) is one of Tokyo’s most popular photographers. Her neon-bright blossoms appear on bullet trains and billboards. They are as recognisable as the real flowers but as traditional, in their 21st-century way, as the prints of Japanese artists running back through the centuries. All are displayed together in this captivating survey of Japanese art – watercolours and painted scrolls, photographs, lithos and woodcuts – with Tokyo at its heart. And every image is a graphic evocation of some stupendous scene that invites the eye to enter in and wander like some spellbound tourist.

Edo – nowadays known as Tokyo – has transformed itself from fishing village to castled city, from the capital of a vast empire to a scintillating, 24-hour metropolis. The city is ever changing and yet somehow always the same. The earliest image here, a 17th-century ink sketch on gilded paper, presents a jostle of rooftops and market stalls, graceful bridges and bustling businessmen. The latest paintings and cibachromes show effectively the same scene in postmodern configurations and hopped-up colours.

It is a city of love hotels, where courtesans entertain their tumescent clients in delicate prints, the merest gap in a kimono acting as a peepshow. Celebrated prints by Utagawa and Hokusai set the scene, alongside contemporary photographs of exhausted ladyboys and modern geishas in false Maybelline lashes.

It is a city of nightlife and noodle bowls, salarymen in sharp suits and thunder-faced actors, bicycles and parasols and figures picking their way through the Tokyo rain and snow across graciously curving bridges. All of which could be happening at any time over the past four centuries, roughly the timespan of this exhibition.

Even the opening images, which show three of Tokyo’s bridges by atmospheric twilight, might be from the same decade. But look closer, and one shows the river below with a subtle tremor, something like electronic interference, and hazy skyscrapers in the distance. It was made in 1993 by Mototsugu Sugiyama. Yet it speaks straight to the 19th-century bridge views of Hiroshige hanging alongside – and with the most palpable reverence.

For that wonderful Japanese tradition of ritualised viewing – of the moon over Fuji, geese against a winter sun, cherry blossom or snow-capped summits – has always had its parallel in art. The Famous Views (of Fuji, or Edo, or the Tōkaidō highway to Kyoto) are such a cherished form of print sequence, and made by so many different artists, it is easy to become confused between them at the Ashmolean. But one series that stands right out, for sheer anomaly, is a collection of Tokyo views from the 1930s.

For almost 80 years, ever since the arrival of American boats in Edo Bay in 1853, and the opening up of Japan to western trade, European artists had learned the lessons of Japanese prints – tilted space, flat planes, absent shadows, abrupt compositional jump cuts. But now, in some kind of curious feedback loop, Japanese artists were imitating the west. These scenes of Tokyo look, briefly, like Whistler Nocturnes or paintings by Degas, before reverting to their own tradition.

The western connections startle every time. Here is the Japanese emperor attending a kabuki performance in 1887, got up like Prince Albert with all the ladies in Victorian crinolines. The Tokyo Tower, exactly modelled on the Eiffel, appears in several cityscapes like a delicate Meccano toy. The first skyscraper emerges in 1898 – but the apex resembles a temple, and the print itself is expressly traditional.

That is one of the high pleasures of this enthralling exhibition. It follows no chronology, gathering all the images around the city itself, like an immutable stage, in which only the players come and go. There are moments of consequent comedy: the 60s Citroën drawn up in front of the Shinto shrine, the manga teen viewing the blossoms, above the fabulous satires of Akira Yamaguchi, sending up the obsession with tradition, particularly in his painting Postmodern Silly Battle.

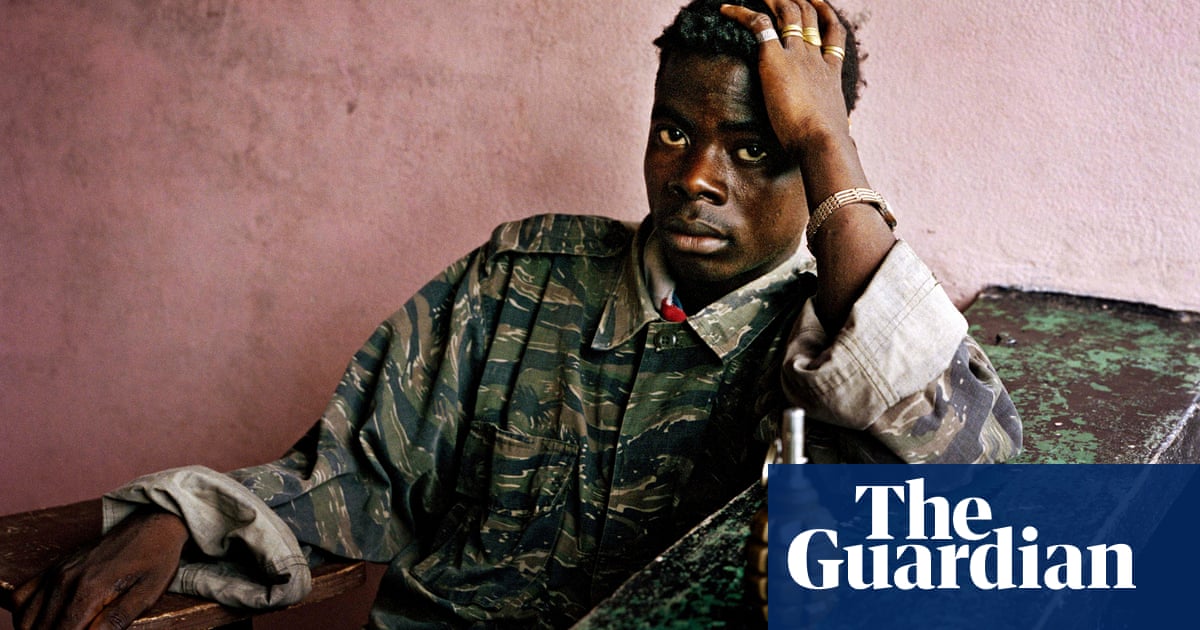

Tokyo rises; but it also falls, victim to earthquake, flood and typhoon. Its destruction in the second world war is the subject of shattering photographs here, but also of astonishing feats of reconstruction. Japanese artists, so sharp-eyed and precise, notice tents for homeless people fronted with brave cardboard doors, and houses ingeniously constructed from umbrellas. The film-maker Meiro Koizumi portrays an actor on a street corner trying to call his dead mother, but always ending up at cross-purposes with random administrators. Mika Ninagawa’s flashbulb photographs illuminate only a 2.5 metre radius, yet they capture a city of lost souls and loners.

But the prints almost always exceed the photographic truths. There is even a deliberate comparison in a black and white shot of a modern prostitute sitting beneath an enlarged woodcut of a courtesan. Only the pale face in the print conveys the absolute isolation of the women – a lunar shape adrift in outer darkness.

This picturing of the world is so unique that every print in this shows draws the viewer more tightly into the scene, trying to work out how the printmaker numbered all those parasols without repetition, how the snowflakes appear to melt on the Tokyo roofs, how the distant fireworks read on the eye so much more explosively than anyone could expect from three scarlet spirals against a paper-white ground.

Its subject may be Tokyo, but this is ultimately a superbly various survey of Japanese graphic art – and most particularly of the incomparable Hiroshige (1797-1858). His prints are so inventive they offer another kind of sightseeing altogether. Sailboats on the sea are tiny white rectangles, outlined in black except for the lower edge where they mysteriously dissolve in water. An eagle spreads its wings above the bay, the water birds below an array of perfectly judged black dots on the waves.

And in his great vision of a sudden shower over a Tokyo bridge, Hiroshige somehow describes the way darkness graduates into light, and air holds moisture in a rainstorm. A black band at the top of the print represents both outer space and the heavy rainclouds shedding their burden. The bay below is turning white. Figures dart across the bridge between, dodging the needle-sharp striations so carefully cut into the image. These are not the literal facts of a downpour, with its billions of droplets, so much as the truth of how it looks and feels.

Tokyo: Art and Photography is at the Ashmolean Museum Oxford until 3 January