Football’s National League started last weekend, while my club Grimsby Town’s first game of the season was one of three in our league postponed due to Covid. This Saturday, at home against Weymouth, marks my first ever game as co-owner of the club with Andrew Pettit in a world changed irrevocably by the spectre of coronavirus. Like many of those who have consumed our football digitally over the past 18 months, it seems that there will be a psychological and physical distance to travel as our supporters return to Blundell Park.

I’ve been wondering if part of the collective experience will be remembering what it feels like, and what it means, to be part of a crowd. Whether we will only fully realise in those moments what has been missing from our lives – as we begin to feel a much broader definition of belonging in a world that has been reduced to the family unit, endless Zoom calls and countless, nameless delivery drivers.For most of my career, I was fortunate to live in London and travel the world. When I used to mention to colleagues or investors that I was from Grimsby, and only ever supported Grimsby Town, it was often met with amusement and derision – sometimes questioned as a sort of misplaced nostalgia or, worse, as a refusal to “escape” from supposedly inauspicious origins.

I lived in north London for more than 20 years and would try to get my football fix by watching Arsenal. I desperately wanted to feel part of the crowd and yet never truly did. I would make the 20-minute walk to the Emirates Stadium from the liberal, middle-class encampment of Crouch End. A Premier League or Champions League game always felt like a high-definition experience, watching multimillionaires shipped in from around the globe elegantly move around a perfect playing surface.

It lacked the emotional element of feeling connected to the people around me. I would often reflect, from my seats high along the halfway line, how similar it felt to watching video game characters move around a screen. It felt like a shared purchase rather than shared experience, because I knew most of the crowd would scatter widely once the game finished.

It is not that elite clubs are not community institutions, rather that they have a whole other life beyond their communities as global corporations. You can be an Arsenal fan from New York or Lagos, but that relationship has a completely different weight if the club represents where your family lives. It’s why Brentford, in their new community stadium, beating Arsenal in the opening game of the season, felt like a compelling symbol of what could be possible.As I have grown older I have become personally preoccupied with the idea of place and where you are from. For all the positives that neoliberalism has ushered in, we have undoubtedly been seduced by the mantra of competitive individualism, the prioritisation of higher education, individual mobility and the idea that rising tides will raise all boats.

In reality we crave a sense of community deep in our DNA and have been wrong to fully believe the high priests of globalisation, who dismissed people who felt a strong connection to their local community. They said there was nothing to be done about post-industrial places that became collateral damage as capital sought higher and higher returns and ignored the towns built on coal, steel, fishing. As we have seen in our politics, people are no longer willing to be ignored.

It’s a truism to state that a club like Grimsby Town represents its community in a different way to the global corporations at the top of the Premier League. I think the questions of what, how and why those differences exist will be partly answered as part of MP Tracey Crouch’s fan-led review, and also in a new initiative on the way the game is run, called Fair Game, of which Grimsby Town is a founder member.

Of all the points being discussed, it seems to me that the most important is the somewhat trite notion that when we talk about community in the context of football clubs, the most important one is the physical gathering of people in one place at one time to share an experience. There are countless other ways to be connected to clubs, but in an increasingly atomised world the idea of physical community isn’t something we often contemplate.

Robert Putnam, in his book The Upswing, writes that capitalism’s original success was partly down to the localised nature of enterprise and the civic institutions that existed as a counterweight to its worst excesses. In today’s public discourse, whether through the idea of “levelling up” or place-based initiatives, there seems to be a recognition that there is truth in this idea and that we need to correct these absences as a political priority. And yet how exactly we do this, and who is pulling the levers, isn’t entirely clear yet.

One thing that is clear is that it will not be achieved by communities being passive recipients of industrial strategy or consumers of government services. Rather it will be a central challenge set and supported by communities anchored by the only vested interest that matters: where their families live.

It seems that we are occupying a post-industrial space in terms of our politics, values and sense of identity. For me, this opens up an opportunity: a shared identity despite all our differences would be a potent symbol of post-Brexit Britain, and a chance to redefine what we want to become and how we want to be heard and represented. An opportunity for us all to redefine values that are not purely economic. Like many political movements before us, it can start with belonging to a crowd and wanting to be heard.

When I read Putnam’s book, it was clear to me that one of the few institutions that have endured and still have such potency are professional football teams. Grimsby Town FC has a 143-year history and a committed, if somewhat diminished, following today. The team can still engender a sense of belonging and an identity that goes beyond the performance of 11 men in black and white on a Saturday afternoon. And that sense of belonging is undoubtedly intensified through physical proximity on a matchday.

Exactly how those bonds can be further encouraged and amplified is a question we can try to answer together.

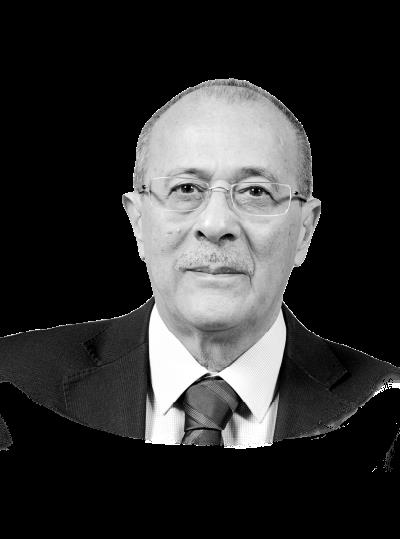

Jason Stockwood is a technology entrepreneur, fellow at Oxford University and chairman of Grimsby Town FC