An insect-like creature is climbing a wall. The wall is made of ice – not regular, firm ice, but ice with spikes and cracks and gaps in behind. The creature has extended arms like a mantis, with sharply angled ends that hook into the ice, as well as spikes on its feet to kick in. Still, it doesn’t look very secure: the ice creaks and bits break off and fall. The creature feels around for somewhere else to stick its hooks and spikes, then continues upwards – intently, methodically, almost mechanically. It is both beautiful and absolutely terrifying.

When the camera pans out, it’s even more terrifying, because of the sheer size of this frozen wall. It is vast and vertiginous, the creature a tiny dot creeping upwards, a gnat in a sweeping sub-zero landscape. Except that this gnat has no wings: if it falls, it falls. Nor does it have a rope, because it’s not a gnat or even an insect, but a man – a Canadian by the name of Marc-André Leclerc, climbing solo in the Rockies with crampons and a pair of ice-axes.

Leclerc is the subject of The Alpinist, a gripping new documentary by Peter Mortimer and Nick Rosen, whose previous films include The Dawn Wall and Valley Uprising, two giants of the climbing genre. The former captures the agonies of Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson as they spend weeks ascending – and vertically camping on – a 3,000ft cliff in Yosemite. The latter is a riotous and occasionally tragic look at how rock-climbing and wingsuit-flying took hold in the same Californian National Park seven decades ago, confounding both the police and gravity.

When Mortimer and Rosen embarked on The Alpinist, Leclerc was pretty much unknown outside of the climbing community in Squamish, a town in British Columbia surrounded by mountains. He sought not publicity but adventure, just went out and did these outrageous climbs, generally alone. But it was precisely this pure approach to climbing, along with his obscurity and astonishing talent, that attracted the film-makers. “It was like if we discovered Neymar playing beach soccer down in Brazil,” says Mortimer on a video call from Boulder, Colorado. The plan was to follow Leclerc and see where he took them. Which was not always easy.

Leclerc, then 23, could be a frustrating subject, sometimes forgetting to tell them he was disappearing into the Ghost River Wilderness of Alberta, or heading to Alaska to climb with his girlfriend Brette Harrington, an elite climber herself. Sometimes he forgot on purpose: when Leclerc went off to do the first ever solo ascent of the Emperor Face of Mount Robson, at 3,954m the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies, he didn’t tell them because he didn’t want them there. “It wouldn’t be a solo for me if somebody was there,” he says in the film. “It wouldn’t even be remotely close to the adventure I was looking for.”

Mortimer compares the experience to making a wildlife documentary. “It’s like filming a wolf in the wild,” he tells me. “Just being there, tracking it, knowing where it’s going to go and getting in the best position. Definitely not distracting – once we’re there, we’re stagnant.”

Rosen, also in Boulder, reiterates the point: they did nothing to rob Leclerc of his focus, nor did they make him do anything he wouldn’t have done had the camera not been there. Then, on top of the ethical issues, there were all the extraordinary logistical ones of filming while clinging to a fragile frozen waterfall or dangling from an overhanging granite wall. “We’re working with a very small group of cinematographers who are also really skilled alpine climbers, the best in the business,” says Rosen. “And that world is so small, they also happen to be friends and climbing partners of Marc-André, so he feels comfortable up there.”

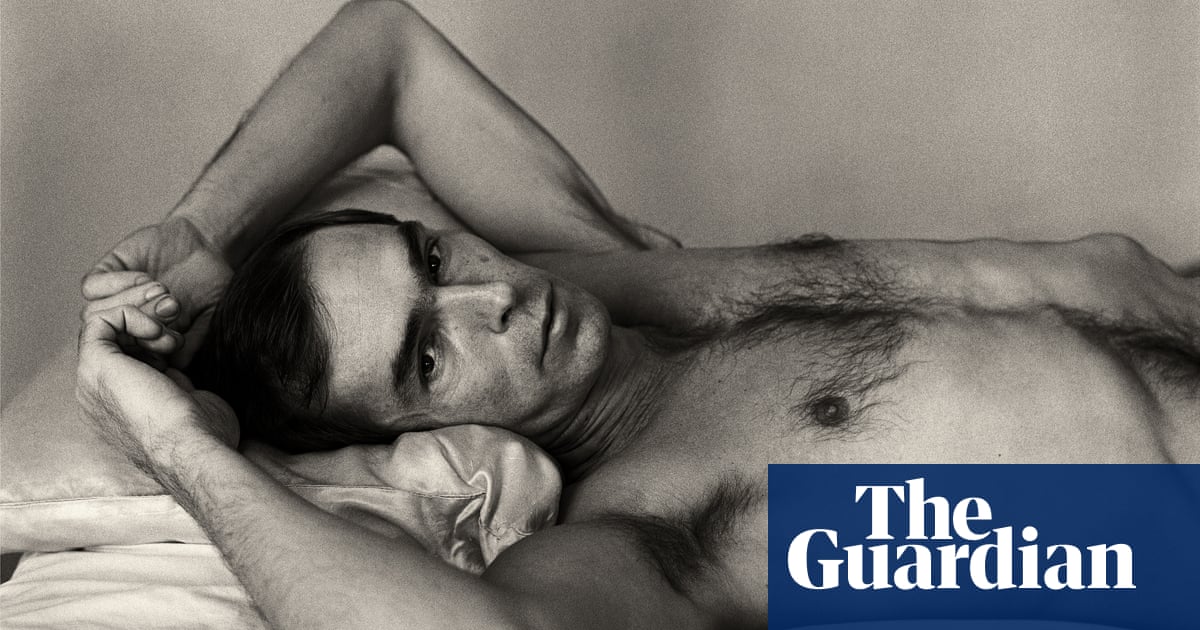

Probably more so than when a camera is pointed at him on the ground. “I’m Marc-André Leclerc, I’m a climber ... generally speaking,” he says, blinking and squirming with embarrassment. But his dorkiness, his wonky-toothed smile, his Butt-Head laugh all add to his appeal. He might not be the greatest of talkers, but there’s an infectious joyfulness about him. And as well as the stunning and buttock-clenching climbing sequences, some of the loveliest scenes in the film are Leclerc hula-hooping with Squamish climbing scene legend Hevy Duty, from Yorkshire (does he really need subtitles?); goofing around with his girlfriend in a bivouac hanging from a cliff; and playing with the kid of the owner of a hostel in Patagonia.

Comparisons with the brilliant 2018 Oscar-winning documentary Free Solo are inevitable. Alex Honnold, the climber that film made a star of for his rope-free ascent of Yosemite’s 3,000ft El Capitan, is a big Leclerc fan and one of the talking heads in The Alpinist. (As Rosen says, Honnold now “side-hustles in explaining climbing to the world”.) Speaking to me from his home in Las Vegas, Honnold points out that there are more variables and therefore more risks in Leclerc’s climbing. “Ice changes hour by hour,” he says. “It’s either freezing or thawing. Rock is mostly permanent. The route I climbed on El Cap will probably remain the same for the next 50 years. The things Marc-André was climbing often fall down at the end of the day.”

But The Alpinist isn’t just Free Solo with snow and ice – Freeze Solo, if you like. The two climbers are very different characters for starters. And, as Honnold points out, climbing may be hitting the big time – it made its debut as an Olympic sport in the summer and climbing gyms are springing up everywhere – but Leclerc’s approach is a throwback to a more romantic, philosophical alpinism of the past. “It was not competitive,” Honnold says. “It was not commercialised in any way. He was just having these outrageous experiences by himself in the mountains.”

And then The Alpinist takes a devastating change of course. In March 2018, as filming neared completion, Mortimer and Rosen got news that Leclerc had gone missing while climbing with a local man named Ryan Johnson in Alaska. Harrington, who was in Australia at the time, raised the alarm after not hearing from him when expected. She immediately flew to Alaska, as did the film-makers and other friends, for an agonising wait as bad weather prevented any attempts at search and rescue. The film goes from being a joyous celebration of the outdoors and adventure to a stark reminder of the risks: the delicate cornice on which Leclerc and others tread, with whooping ecstasy on one side and a dark chasm on the other.

“I miss him more than I can express,” says Harrington, talking to me from Banff, Alberta. “We basically spent our entire adult life together. I met Marc when he was 19 and I was 20 and we just started climbing together, doing everything together. He was my best friend.”

The bodies were never found, just a piece of red rope poking out from a mass of heavy snow. After successfully summiting a new route on the Mendenhall Towers, it seems they were consumed by an avalanche on the descent. Leclerc was 25, Johnson 34.

Everyone agreed the film should go ahead. After taking some time out, Mortimer and Rosen did two more interviews, with Harrington and Marc-Andre’s mother Michelle Kuipers, but otherwise the structure remained the same. “We really felt we had to include the grief and the people who were most affected,” says Mortimer. “We were trying to tell an honest complete story about this person – and that is part of the story.”

A story not just of adventure and stunning vistas but one of loss, a point Honnold appreciates. “I’ve had a lot of friends die climbing but I haven’t seen a lot of the aftermath. That was one of the more powerful parts of the film, seeing what effect Marc-Andre’s death had – on his girlfriend, his family, his community.”

It hasn’t stopped Harrington from climbing. She’s carrying on what they used to do together. “More than anything else,” she says, “Marc loves ... loved to have fun.” She does that, seems to forget and speaks about him in the present tense. “That’s why I need to continue enjoying life.”

Harrington has been back to mountains they climbed together, and to ones they were planning to, managing a fiendish first ascent of a route up Patagonia’s Torre Egger, which she named MA’s Vision in his memory. While she never felt invincible before, she says, “I didn’t realise how close death could be. Now I’m more sensitive to how fragile we are as people.”