When Granta produced its first Best of Young British Novelists list in 1983, a handful of the featured authors – Amis, McEwan, Rushdie – hoovered up coverage. But also on the list was Nigerian-born Buchi Emecheta, who continued publishing novels until 2000 (she died in 2017) but didn’t get the column inches. So it’s a late justice that she is one of the few Granta alumni, alongside Martin Amis and Shiva Naipaul, to be promoted to the Penguin Modern Classics list.

Second-Class Citizen (1974) was Emecheta’s second novel and a prequel to her debut In the Ditch, though it stands comfortably alone. She called them “documentary novels”, closely based on her life as an immigrant to England in the 1960s. The centre of the book is Adah Ofili, a young woman who pursues a series of dreams: to go to school, to win a scholarship and, ultimately, to go to England. On the last, “she dared not tell anyone; they might decide to have her head examined or something”, but when she sees educated doctors coming from England to work in Nigeria, she knows she is right.

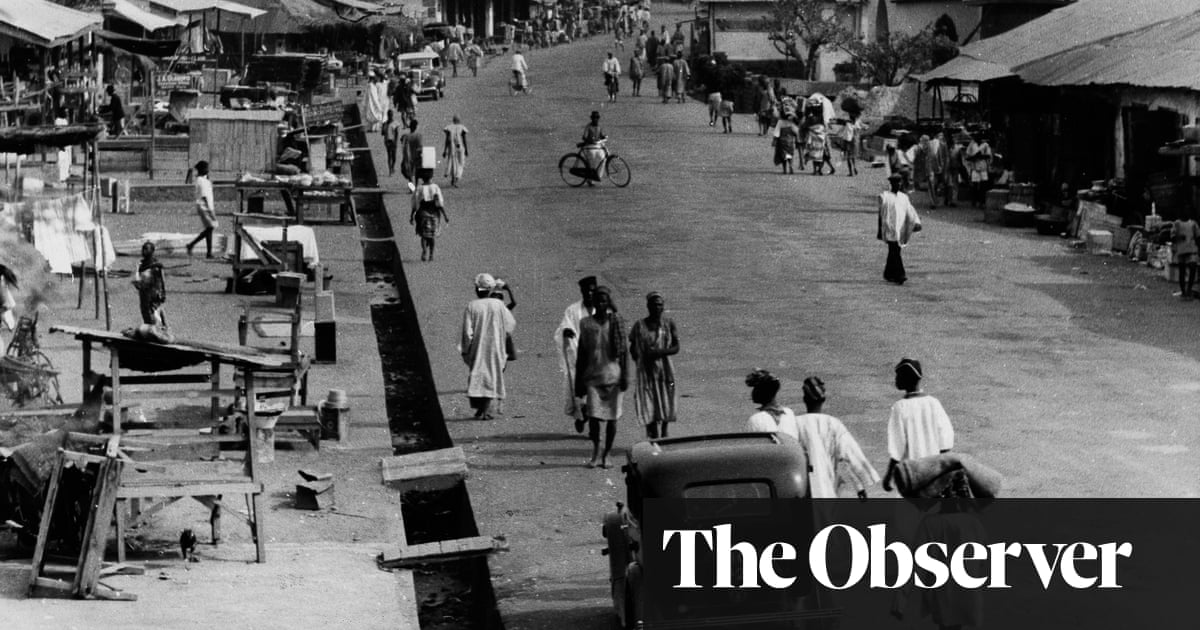

Adah must forge her own way while complying with local traditions: she marries at a young age (to Francis) and soon has two children. Life in Nigeria is described only partially – her marriage and first job occupy less than a page – and it’s clear that Emecheta, like her heroine, is impatient for life in England. Adah and Francis arrive by boat – “Liverpool was grey, smoky and looked uninhabited by humans” – and head to London, where they struggle to find somewhere to live (“Sorry, No Coloureds”).

Where they end up is among other immigrants, but Adah, who had been an elite in Lagos, is appalled at having to live alongside Nigerians who were “of the same educational background as her paid servants”. But as Francis points out, “the day you land in England, you are a second-class citizen. So you can’t discriminate against your own people, because we are all second class.”

Adah’s story is commonplace but unique: sick children (three more arrive by the end of the book), racism and domestic violence. The thing that never fails her is her resourcefulness, the ambition that takes her to England and later fuels her determination to be a writer. She observes the distinctions between Nigeria (churches have a “festive air”; she can “go to her neighbour and babble out troubles”) and England (“cheerless” churches; “nobody was interested in the problems of others”). Her Nigerian language, Adah says, makes “a song of everything”, but Emecheta is not a showy stylist. The simple, informal prose gives the story a durability: it’s still fresh even without its on-trend autofictional form or timeless subject matter of the black woman’s experience in Britain.

Emecheta’s son wrote recently that the book’s portrayal of his father – Francis in the novel, who assaults Adah and burns the manuscript of her first book – is “perhaps selective”. But selectivity is an author’s job and it’s this that makes Second-Class Citizen not just a representation of a life, but a lively work of art.