English cricket has descended into crisis after Azeem Rafiq’s powerful testimony laid bare its institutional failings on racism, bullying and dressing room culture while also alleging a past drugs cover-up by Yorkshire.

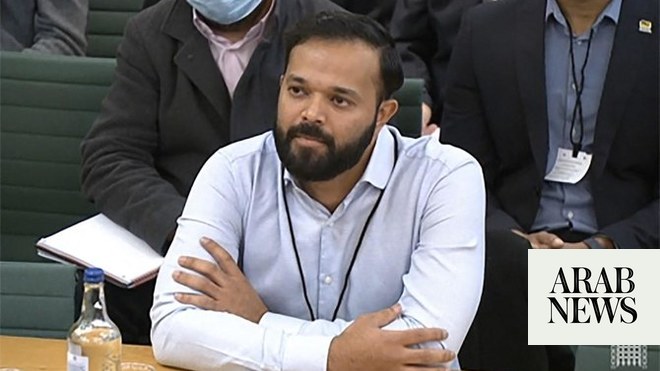

This was a day that the sport will never forget – nor should it – as Rafiq sat in front of the digital, culture, media and sport select committee and outlined his harrowing experiences at Headingley, summed up by six simple words that must now prove a watershed moment: “I lost my career to racism.”

For nearly two hours Rafiq fought back the tears, detailing the dressing room he first entered in 2008 – one in which phrases such as “Paki”, “elephant washers” and “you lot” were commonplace – through to his release in 2018, just months after his first child was stillborn and allegations of racism were ignored.

It was not about individuals, Rafiq insisted, but rather cricket as a whole, with the former England Under-19s captain claiming he had been told similar stories by players at Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire and Middlesex and describing the “inept” handling of his complaints by the Professional Cricketers’ Association.

Certainly the panel of MPs chaired by Julian Knight looked to broaden the inquiry, subjecting the England and Wales Cricket Board, led by Tom Harrison, to a stiff interrogation that highlighted the governing body’s record on diversity, its conflict as both regulator and promoter and, ultimately, took a dim view of its inaction after Rafiq first blew the whistle last year.

Nevertheless, names such as Matthew Hoggard, Tim Bresnan, Michael Vaughan, Gary Ballance and Andrew Gale emerged, to varying degrees, as alleged perpetrators during Rafiq’s two spells at Yorkshire between 2008 and 2018, with the former off-spinner starting proceedings and speaking freely without fear of legal reprisal under parliamentary privilege.

The devastating allegations portrayed a toxic county dressing room that paused only during Jason Gillespie’s spell as head coach from 2012 to 2016. These were later expanded upon further when the DCMS published the witness statement Rafiq had submitted during the recently settled employment tribunal case; a 57-page document that is, frankly, incendiary.

In this Rafiq claimed he was regularly called “Raffa the Kaffir” by Hoggard – the former England seamer personally apologised for this in 2020 when Rafiq first spoke up in the media – and bullied by Bresnan. Speaking yesterday, Rafiq said he was among a group of players who reported Bresnan to the club over the bullying allegations, only to find himself singled out and painted as a “troublemaker”.

Rafiq also gave a heartbreaking retelling of Yorkshire’s indifference to the death of his first child, accusing Martyn Moxon, the director of cricket, of having “ripped the shreds off me” on his return to the club and claiming that Gale, who had moved from the role of captain to head coach by this stage, showed no sympathy.

A running theme of both Rafiq’s oral and written submissions was a sense of being treated differently from white players – something that has been echoed during recent allegations at Essex – and at one point in his statement he alleged that Ballance, a player whom he claimed used regular racial slurs in the dressing room, was allowed “to miss drug hair sample tests to avoid sanctions”.

“When he failed a recreational drug test and was forced to miss some games, the club informed the public he was missing games because he was struggling with anxiety and mental health issues,” Rafiq added in his statement. A legal representative for Ballance subsequently denied the allegations.

The revelations went beyond the Headingley dressing room, with Rafiq alleging during his evidence session that the use of the word “Kevin” by Ballance to describe people of colour had bled into the senior England set-up. Alex Hales, he claimed, was rumoured to have named his black dog accordingly. Either way, the link to the national team will prompt further questions in the coming days.

Rafiq also responded to the recent assertion by Joe Root, the England Test captain, that he could not recall any specific instances of racism during his 14 years at the club. Asked about this, the former off-spinner replied: “Rooty is a good man, he’s never engaged in racist language.

“[But] I found [his comments] hurtful. He was Gary’s flatmate. He was involved in social nights out during which I was called a Paki. He might not remember [the incidents of racism] but it shows how normal it was that even a good man like him doesn’t see it for what it is.”

Asked if anyone had stood up for him during this time, or when as a 15-year-old at Barnsley Cricket Club he had wine poured down his throat despite this going against his Muslim faith, Rafiq replied: “You had people who were openly racist and you had the bystanders. No one felt it was important.”

This agonising watch was followed by evidence from the former Yorkshire chair, Roger Hutton, and his successor in Lord Kamlesh Patel. Both Mark Arthur, chief executive until last week, and Moxon, currently signed off for stress, had declined the invitation to attend and were criticised for this by Knight.

In this Hutton tried to explain the club’s handling of Rafiq’s allegations and the resistance that followed internally when, after a 12-month investigation that began in September 2020, the club’s report was produced. For Hutton the blame here lay with both Arthur and Moxon, the board members whom he claimed were unable to “accept the gravity of the situation”, refused to apologise and would not move on the recommendations that the panel put forward.

Hutton claimed he was unable to stand the pair down as the Graves Family Trust, owed more than £15m by the club, had a veto on board members. After this apparent blockade was scrutinised by the MPs, and later bemoaned by Harrison despite previously working under Colin Graves at the ECB, Hutton was asked if Yorkshire was institutionally racist and replied: “I fear it falls into that definition.”

This conclusion was further than Harrison was prepared to go, with the ECB chief executive insisting only the handling of Yorkshire’s investigation into Rafiq’s claims could be described as such and stressing the convoluted process by which the governing body, as the sport’s regulator, could not step in sooner.

By this stage Harrison, joined by two executives and the ECB board member Alan Dickinson, had already infuriated his interrogators with indirect answers that were riddled with corporate jargon. This contrasted hugely with Rafiq’s earlier testimony, spoken without notes, from the heart and in everyday language, despite having little of the same training.

“I want to become the voice for the voiceless,” the 30-year-old had said. In a sport in which 30% of the recreational game is made up by the British Asian community, only to see this drop to 4% at professional level, this may prove to be his legacy.