Grandi said UNHCR works in highly politicized situations, and increasingly it has to deal with “de facto authorities” who are not internationally recognized but control areas in many countries where it operates because people need help

UNITED NATIONS: The growing inability of the international community to restore peace in countries like Yemen, Libya and Ethiopia is forcing humanitarian and refugee organizations to work increasingly during conflicts which they can’t solve despite the expectations of many people caught up in these crises, the UN refugee chief warned Tuesday.

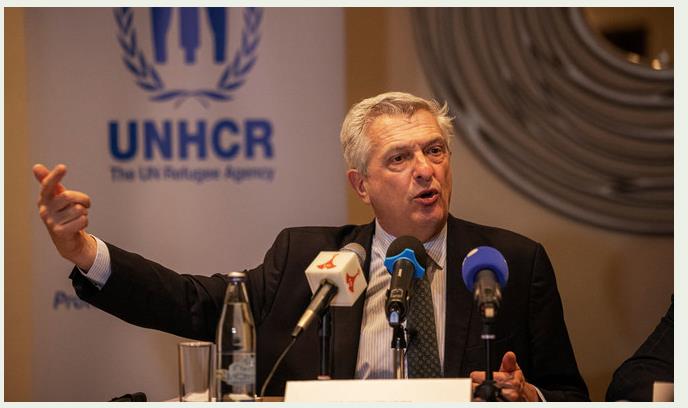

Filippo Grandi reminded the UN Security Council that in the absence of political solutions to conflicts — “and those political solutions seem to be more and more scarce and far apart” — the consequences on people caught in these violent confrontations “continue to become more and more serious.”

The UN high commissioner for refugees said his office and other organizations are dealing with about 84 million refugees who fled across borders and people displaced within their own countries, trying to provide humanitarian support, shelter and safety.

Grandi spoke to the council and UN correspondents from Geneva where donors pledged a record of more than $1 billion Tuesday to support UNHCR’s work in 2022. While he welcomed their crucial support, Grandi said the pledges won’t be enough to support the growing challenges the agency foresees next year, largely driven by conflict, climate change and COVID-19.

The high commissioner said UNHCR is appealing for nearly $9 billion to cover its operations in 136 countries and territories next year. Almost half the money is for emergencies to assist a record number of forcibly displaced people, especially in the Middle East and Africa as well as millions who have fled their homes in places like Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Venezuela and beyond, he said.

Asked whether he saw any hope for the many millions of refugees and displaced people in 2022, Grandi said “I see glimmers of hope everywhere — if certain things are done.”

“The question is will these things be done?” he asked. “Will states cooperate more to try and solve these issues? Will more resources be put into responses? Will be will the neutrality and safety of humanitarian operations be granted?”

“I remain not terribly optimistic about progress on these matters, especially on cooperation and the search of solutions,” he said.

Grandi said if it took “excruciating negotiations” in the Security Council to get approval to continue delivery of humanitarian aid through a single crossing point from Turkey into Syria, “then we are in trouble, then we cannot really aim at moving forward.”

“So yes, I think the prospects, unfortunately, are rather grim in terms of the size of the problem and the complexity of the causes,” he said.

Grandi said UNHCR works in highly politicized situations, and increasingly it has to deal with “de facto authorities” who are not internationally recognized but control areas in many countries where it operates because people need help. These situations are very often complicated by political difficulties, sanctions and other restrictions on dialogue and engagement which aggravate the provision of humanitarian needs, he said.

Grandi said he is often warned by countries that UNHCR should not politicize humanitarian action, but “I keep reminding states that if anybody politicizes humanitarian action it is the states, not the United Nations as an institution, not UNHCR for sure.”

Nonetheless, he said, UNHCR is being accused by all sides in Ethiopia, for example, of supporting the other side which he warned is not safe for its staff or conducive to effective humanitarian action.

“We operate in context in which there is more burden, expectation that humanitarian actors can solve problems, when in reality, the space is reduced even for us to save lives,” he said.

Grandi said he just returned from a tour of Mexico and northern Central America where he saw “the incredible complexity of the causes of displacement” — conflict, human rights abuses, violence by criminal gangs, poverty, inequality, climate change and an inadequate response by states.

He said the complexity of causes in Central America, Africa’s Sahel region, and elsewhere leads to “increasingly complicated forced displacement.”

Grandi said his message to the Security Council was to focus on one of the causes — conflict — because if progress can be made toward stability then perhaps “the vicious circle” leading to the displacement of millions of people can be unblocked.

He also appealed to the council to provide “the widest scope for humanitarian exception” to UN sanctions on Afghanistan’s new Taliban rulers to help the 23 million Afghans facing extreme levels of hunger and other humanitarian challenges.

Grandi warned that a widespread implosion of the Afghan economy will almost inevitably trigger a much bigger exodus of Afghans seeking a better life in neighboring countries and beyond.

“This is something that can still be prevented at this point, but it requires quicker action” to ensure that the economy functions including the flow of cash and services, he said. this with its leaders.