Australia will export its first load of liquefied hydrogen made from coal in an engineering milestone which researchers say could also lock in a new fossil fuel industry and increase the country’s carbon emissions.

Under the $500m Hydrogen Energy Supply Chain (HESC) pilot project, hydrogen will be made in Victoria’s LaTrobe valley from brown coal and transported aboard a purpose-built ship to Japan, where it will be burned in coal-fired power plants.

Carbon capture and storage will be used in an attempt to reduce the carbon emissions associated with making the hydrogen and supercooling the gas until it forms a liquid before it is loaded aboard the Suiso Frontier vessel. The first shipment is due to depart from Hastings in the coming days.

The project is being led by a Japanese-Australian consortium including Japan’s J-Power, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Shell and AGL.

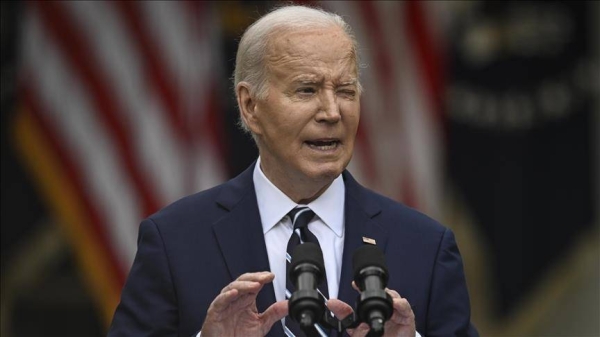

The prime minister, Scott Morrison, said on Friday the development was a “world-first that would make Australia a global leader” in the budding industry.

“A successful Australian hydrogen industry means lower emissions, greater energy production and more local jobs,” Morrison said in a statement.

“The HESC project puts Australia at the forefront of the global energy transition to lower emissions through clean hydrogen, which is a fuel of the future.”

Morrison also announced an additional $7.5m to support the next stage of the project, which has a goal of producing 225,000 tonnes of carbon-neutral hydrogen each year and an additional $20m towards the next stage of the CarbonNet project which aims to produce commercial-scale carbon capture and storage.

According to government estimates, this will reduce emissions by 1.8m tonnes a year.

But Tim Baxter, a senior researcher for climate solutions at the Climate Council, said the assumptions were questionable as the reliance on “fossil hydrogen” meant government needed to “come back with a zero emissions hydrogen plan”.

Sign up to receive an email with the top stories from Guardian Australia every morning

“Hydrogen derived from fossil fuel sources, like what is being shipped out of the LaTrobe Valley, which is derived from some of the world’s dirtiest coal, is really just a new fossil fuel industry,” Baxter said.

“Fossil hydrogen is a whole new fossil fuel industry, regardless of whether carbon capture and storage is attached to it. It results in extraordinary greenhouse gas emissions. It’s not a climate solution.”

Though “clean hydrogen” has become central to the government’s emissions reductions plans, hydrogen produced by fossil fuels is more expensive, will release more greenhouse gas emissions and comes with greater risk of creating stranded assets.

Dr Fiona Beck, an engineer with the ANU Institute for Climate, Energy and Disaster Solutions, said Friday’s announcement did mark an engineering milestone as it showed it was technically possible to liquefy and store hydrogen for transport, as this was more difficult to do than with LNG.

However, Beck, a co-author of a recent peer-reviewed paper published in the Journal of Cleaner Production that examined the emissions that will be created out of the proposed Japanese-Australia hydrogen supply chain, said if hydrogen made with fossil fuels became the norm, Japan would be transferring its emissions to Australia.

Japan, which has limited options for onshore wind projects, has been looking for ways to reduce its CO2 emissions. One way is by burning ammonia, which is made with hydrogen, in its coal-fired power plants – which are also powered with Australian coal.

Under current CO2 accounting standards by which emissions are measured, Japan would slash its emissions while shifting them across to Australia owing to the CO2 emissions involved in creating, processing, transporting and shipping the hydrogen.

“If you’re importing hydrogen made from coal, essentially the emissions are going to be worse in Australia rather than it would be by just taking that coal and burning it in Japan,” Beck said.

“There’s no policy pressure or economic reason why Japan would buy low-emissions hydrogen when it gets the same benefit by buying cheap, high-emissions hydrogen.”

Beck said that while current government planning stated its intention to reduce emissions associated with creating hydrogen “there’s very few actual mechanisms to do this”.

“Unless Australia has some strong policy to keep its carbon emissions down, we could see a rise in emissions in Australia due to this hydrogen trade.”