The first thing Martin Glass thought about was his daughter, when he heard the news on Monday evening that his home town team, Raith Rovers, were signing a man ruled to be a rapist by a civil court.

Lillie is just seven and a half months old but 26-year-old Glass is a first-time dad and he’s already looking forward to taking her to her first game. “I want my daughter to have good role models. If I’m part of a club that has a rapist as an idol then that’s on me.”

His second thought was to set up a fundraising page for Rape Crisis Scotland. “Let’s make a difference,” he wrote, introducing the online appeal. By Friday morning, he had raised more than £12,000.

“I needed to show Raith and football fans in general did not support this,” Glass said. “It’s a small bit of good out of the darkest moment in our club’s history.”

Raith Rovers’ decision to sign David Goodwillie, who was ordered to pay damages to the woman he was found to have raped in a landmark case in 2017, resulted in a ferocious backlash that escalated as the week progressed, with sponsorship withdrawals, multiple resignations and the women’s team moving to sever ties.

On Thursday, the Scottish Championship club announced in a contrite statement that it had “got it wrong”, would not select Goodwillie and was reviewing the 32-year-old striker’s contract.

But Glass echoes many Raith supporters whose response to the U-turn has been only a qualified welcome. “If this is all that happens, I won’t be back this season. The board should resign: they came up with this, they should take the consequences rather than the fans, volunteers and players.”

Aileen Campbell, the chief executive of Scottish Women’s Football, agreed that the statement on Thursday was “only the first step” in rebuilding trust with supporters.

While questions have been raised about why there was not a similar reaction when Goodwillie returned to Scotland to play for Clyde in 2017, Campbell said this week’s outcry marked a shift in expectations in recent years. “It shows that society has moved on and we don’t want this to be part of our game.”

As head of the governing body for women’s association football in Scotland and a former Scottish government sports minister, Campbell’s priority this week has been offering support to the women’s team, describing the impact on the players and ensuing spotlight as “overwhelming”.

It is ironic, she adds, that the women’s team was forced to seek alternative sponsorship and a new ground at which to play, at a time of growing momentum for the women’s sport.

“We’re at a really important juncture in the game with the visibility of women’s football increasing, as well as generating that critical financial support and sponsorship. There is lots of scope for it to grow and we have inspiring role models, women who have often defied the odds in combining work and family.”

Eve Ralph, a football coach co-founder of Her Game Too, a campaign set up by 12 female fans last summer with the aim of ending sexism in football, believes the conversation among football supporters is changing too.

“Football culture across the UK has come a long way, with more women going to matches and men more likely to call it out if their friend says something unacceptable. There’s more discussion about what’s acceptable behaviour and what’s not”.

High-profile arrests for alleged sexual violence, including of the Manchester United forward Mason Greenwood on Sunday, have raised questions about how Premier League clubs handle such allegations.

“There’s still a sense that a lot of players are not facing the consequences for their actions,” says Ralph. A Bristol City fan, she mentions how Women’s Aid ended its partnership with the club last year after it signed Danny Simpson, a player with a domestic abuse conviction. “Footballers are huge role models for men and women, and the attitude of ‘he’s got a past but he’s a great player’ has a terrible effect on anyone who may think ‘I can get away with it if I’m famous’.”

Some younger Raith fans have pointed out that one of the only sections of supporters supporting Goodwillie are some of the teenage boys who make up Raith’s youth fanbase. One young woman told the Guardian: “They’re the ones on Instagram saying it’s really unfair. To them he’s just some guy who got away with a threesome.”

“Some people will say Goodwillie deserves a second chance,” says the SNP MP Hannah Bardell, who spent four years working at Livingston FC before she became a politician. “But there have to be boundaries around certain crimes, and yet again this is putting men’s careers over women’s lives.”

Bardell contrasts Goodwillie’s lack of public contrition – which she accepts may be legally advised – with that of David Martindale, who was made Livingston manager last year amid some controversy, having spent time in prison for drug dealing. “These are complex questions and we need to have a framework that enables us to make these fine judgments. Rehabilitation is a cornerstone of any civilised society.

“Nobody’s saying Goodwillie shouldn’t be able to live his life, but being a footballer at that level, being a role model, is difficult.” This is part of a broader discussion, she says, about the pedestal footballers are put on, how much they are paid, and the culture surrounding them.

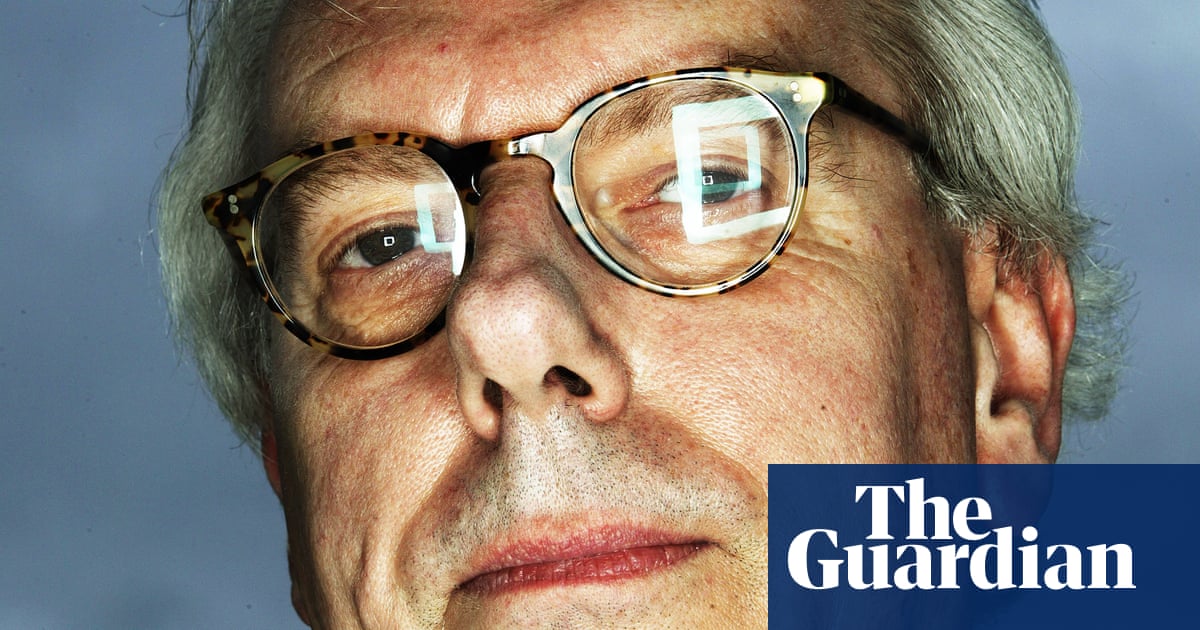

After withdrawing her shirt sponsorship from the men’s team on Tuesday, the crime writer and devoted Raith fan Val McDermid stepped in to pay for new strips for the women’s team, without the club crest.

This Sunday, Bardell will head to Windmill Park, Kirkcaldy, to watch the recently renamed McDermid Ladies play at 2pm. The women’s team are expecting a big crowd.