A child under the age of 12 is in dire need of medical attention, as is a 49-year-old woman

Canadian policy allows the repatriation of Daesh members and families, but the government has not acted

LONDON: Rights group Human Rights Watch (HRW) has implored the Canadian government to abide by its own rules and let a gravely ill Canadian child, who is under 12, return to Canada from a Daesh internment camp in Syria to receive life-saving healthcare.

The group also urged Canada to repatriate a 49-year-old woman, Kimberly Polman, who is not the child’s mother but is also gravely ill.

“How close to death do Canadians have to be for their government to decide they qualify for repatriation?” said Letta Tayler, associate crisis and conflict director at HRW.

“Canada should be helping its citizens unlawfully held in northeast Syria, not obstructing their ability to get life-saving health care. If this Canadian woman and child die in locked camps and prisons in northeast Syria, Canada would share the blame.”

HRW said: “Canada is effectively preventing a Canadian woman and a young Canadian child detained in northeast Syria from coming home for life-saving medical care despite a Canadian policy allowing them to do so.”

Ottawa has said that repatriating its nationals could pose a security risk and that it is too dangerous for its diplomats to travel inside war-torn northeast Syria to extract them.

However, if they can reach a consulate then the government has said it will assist them, and Canada will “consider” repatriations of its nationals in Syria on a case-by-case basis, according to new policies introduced in early 2022.

Those conditions are highly restrictive but “could include” an “imminent, life-threatening medical condition, with no prospect of receiving medical treatment (on site),” according to a copy of the policy framework reviewed by HRW.

Former US Ambassador Peter Galbraith, who has taken several foreigners out of northeast Syria on behalf of their home countries, told HRW that Canadian authorities had refused his offer to escort the woman and child to a Canadian consulate in neighboring Iraq.

Galbraith told HRW that all he needed to proceed was for a foreign affairs official from Canada to email a ranking official from the Kurdish-led authorities in northeast Syria stating that Canada would not object if he took Polman and the child across the border to Erbil.

“Canada’s position appears to be this: It is too dangerous to send our diplomats into Syria to help Canadian citizens detained in Syria, but we will provide consular services to any Canadian who reaches a Canadian diplomatic mission,” Galbraith, who left northeast Syria after Canada rejected his offer on Feb. 15, told HRW.

“However, Canada will also not make it possible for a Canadian detained in Syria to actually reach a Canadian diplomatic mission.”

On Feb. 10, more than a dozen UN independent experts called on Canada to urgently repatriate Polman to treat life-threatening illnesses including hepatitis, kidney disease, and an autoimmune disorder.

They said conditions in the locked camps holding Canadians and other foreigners met the threshold of torture and cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment.

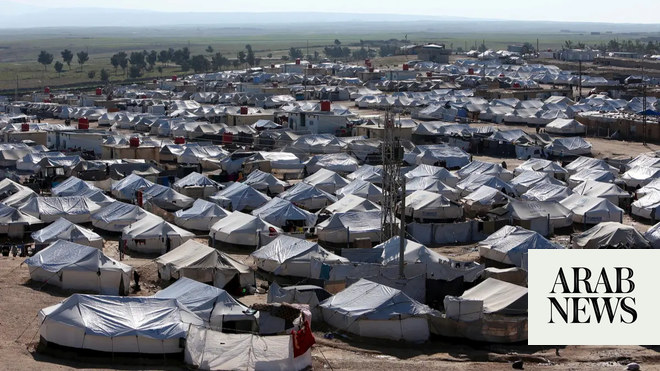

Kurdish authorities have repeatedly urged Western countries to bring home their nationals — an estimated 40,000 foreigners — who had traveled to Syria to join Daesh. Among the foreign fighters and their families are an estimated four-dozen Canadians.

However, most have been slow to repatriate nationals, and Canada has, to date, only brought home a five-year-old orphan and a four-year-old girl and her mother.

Hundreds of detainees have died of preventable illness, accidents, or violence between detainees or detainees and guards, and in January a major Daesh assault on a prison in Hasakah sparked a 10-day battle that left hundreds dead, including children.