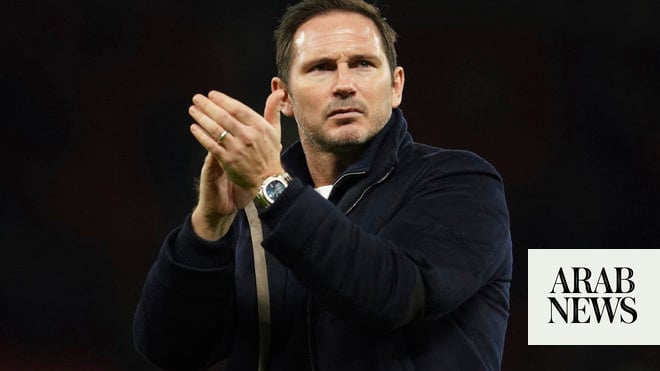

“Every new coach wants to be high press, high energy, win the ball back, play quickly, all that stuff, there’s nothing new in that,” Frank Lampard scoffed to Gary Neville last year, in one of the many media interviews he gave during his extended break from management. And he was right, of course. Pretty much every young manager who emerges off the Uefa Pro Licence course seems to have the same few stock phrases to hand: a broad-brush managerial philosophy that is so vague as to be essentially meaningless.

Late last month Lampard finally made his return to management at Everton, and in his first press conference outlined the way he wanted his new team to play. “When I think of Everton, it’s a team that loves to see crosses and pressure and second balls, shots and combinations and things done at speed, a team that wants to run and a team that wants to press high up the pitch,” he said. “Those things absolutely align with my philosophy.” A textbook sales pitch. Of course, as Lampard well knows, the devil of coaching is not in the theory but in the practice, and thus far it’s fair to say the practice has been mixed: two convincing home wins and two convincing away defeats. By the time Everton play on Saturday evening, they could be in the Premier League relegation zone for the first time since Marco Silva was sacked more than two years ago. Their opponents? Manchester City.

“Enjoy the ball,” Lampard was heard urging his players during one of his first training sessions, and a key early focus has been on converting a scarred, scared Everton squad into a team comfortable in possession. The arrivals of Donny van de Beek and Dele Alli are a clear attempt to augment the level of technical ability in midfield. Everton’s ball retention under Rafa Benítez was one of the worst in the Premier League. But in truth the decline had begun to set in even earlier than that.

Under Roberto Martínez and Ronald Koeman, Everton were habitually among the top eight Premier League teams in terms of possession. Ever since Koeman’s sacking, a clear trend has emerged. Possession fell under Sam Allardyce (even if results improved slightly), rose briefly under Silva, fell again under Carlo Ancelotti and then fell away almost entirely under Benítez. This feels not so much like a blip as a cultural shift, habits that have been unlearned and rewired over years rather than months, an entire football club that seems to have forgotten how to pass the ball.

Take Tom Davies, one of the few constants in a rapidly-changing Everton squad over the last few years. In 2018-19, the season after he turned 20, he was an integral part of an attacking passing-based team, with stats to match. Three years on, those numbers have plummeted. Average passes per 90 minutes are down from 48 to 33. Successful long balls down from 5.2 to 1.7. Passes into the final third down from 4.5 to 1.1.

The same player, at the same club, in what should have been the prime learning years of his career. Instead, due to a combination of poor luck with injuries, poor planning and a poorly-defined team identity, it’s hard to know where he goes from here. André Gomes is a similar story, a midfielder of promise whose career seems to have gone gently into reverse from the moment he set foot at Goodison. It’s easy enough to point the blame at individual players for underperforming, but when they are so clearly part of a broader long-term pattern it’s hard not to conclude that the failure is systemic.

The question is whether Lampard is capable of reversing any of this, or whether – in common with his time at Derby and Chelsea – he will shift the spotlight on to his players when results start to turn. “We stopped trying to play,” he complained after the defeat by Southampton. “When the game turned we reverted to type and lacked belief.” Which is all very well when you’ve only been in the job for a few weeks. But there comes a point when this kind of becomes your responsibility.

At the heart of this project, then, lie a number of unknowns. What really defines Lampard’s managerial philosophy beyond a set of handy buzz-phrases and a vague idea of progressive football? How realistic is it to impose a radical style change in the middle of a relegation scrap? And – most pertinently of all – what constitutes success here? Is it really enough for Lampard to steer Everton to 17th place? Or should the league’s seventh-most expensive squad be held to a higher standard? Part of the reason this is such a gamble on Everton’s part is that we have no real way of assessing Lampard’s ability to effect genuine change. He inherited good squads from Gary Rowett at Derby and Maurizio Sarri at Chelsea, and each time performed reasonably well for one season without ever really changing much.

Everton is a different challenge entirely: a dysfunctional club that requires more than a positive attitude and some choice phrases. It requires an identity beyond “high energy and high pressing”, an aspiration that goes further than simply wanting to be a big club again, a sense of wider purpose beyond positioning its celebrity manager for his next job. Above all, it needs time and a vision. At this admittedly early stage, it is not entirely clear whether Lampard has either.