In The Andy Warhol Diaries, a new six-episode Netflix documentary executive-produced by Ryan Murphy, the familiar details of the artist’s life are mostly covered within the first hour. There’s his tortured youth in Pittsburgh, where he drew portraits of his fellow schoolmates in attempts to stop their bullying; his early fondness for Campbell’s tomato soup; and his eventual escape to New York in 1949, at the age of 20. There, after transitioning from graphic design to fine art, he launches The Factory, his storied and sometimes exploitative studio in Union Square; he exhibits his first soup cans in 1962 and, by 1968, reaches pop stardom.

Director Andrew Rossi’s focus, however, is mainly on the inner life Warhol painstakingly hid from view, namely the artist’s fraught relationship with his own homosexuality. “I grew up to understand my sexuality as a bisexual man in a very homophobic environment, and so he was a hero, always,” Rossi tells the Guardian, “but I never knew the details of his life.” In his reading of the original Andy Warhol Diaries, the artist’s titular memoir published in 1989, what he found was “not just a manipulative monster, or a happy fool, but rather a humanity that plays out in these very beautiful and intense romantic relationships”.

The resulting documentary unfolds in a collage of found and recreated footage, based primarily on diary entries expressing Warhol’s great love for three main protagonists: the interior designer Jed Johnson, with whom he spent 12 years; the Paramount Pictures vice-president Jon Gould; and the painter Jean-Michel Basquiat. (By all accounts, the artists’ friendship was strictly platonic, but Diaries shows that Warhol’s attraction to Basquiat was partly paternal, partly sexual and partly opportunistic.) The dominant mood is a profound loneliness, as a version of Warhol’s voice, a combination of the actor Bill Irwin and the slightly robotic drone of artificial intelligence, reads passages from his diary. “When I think of my high school days, all I can remember are the long walks to school, past the babushkas and the overalls and the coal signs,” it says, as the camera pans over stunning B-roll of Pittsburgh’s industrial architecture.

“I wasn’t very close to anyone, although I guess I wanted to be, because when I would see the kids telling one another their problems, I felt left out.”

As far as Warhol’s relationships, “The fact that Andy shared a bed with Jed is something that not a lot of people know,” Rossi notes; the artist had been intensely private about his personal life. The suffocating homophobia that he had fled in Pittsburgh was also alive and well when he arrived in New York, where fellow queer artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns projected an aura of machismo that he could not. “They thought he was too swish,” gallerist Jeffrey Deitch says in episode one, deploying the derogatory slang of that era. Warhol felt a sense of alienation not only in the predominantly straight art world, but in queer spaces, too: “It was all guys with beards and lumberjack shirts and leather pants, and you know and he didn’t qualify within 10 miles of that,” according to critic Lucy Sante. “He was conscious of being unattractive, and that weighed heavily on him, going back to his childhood.”

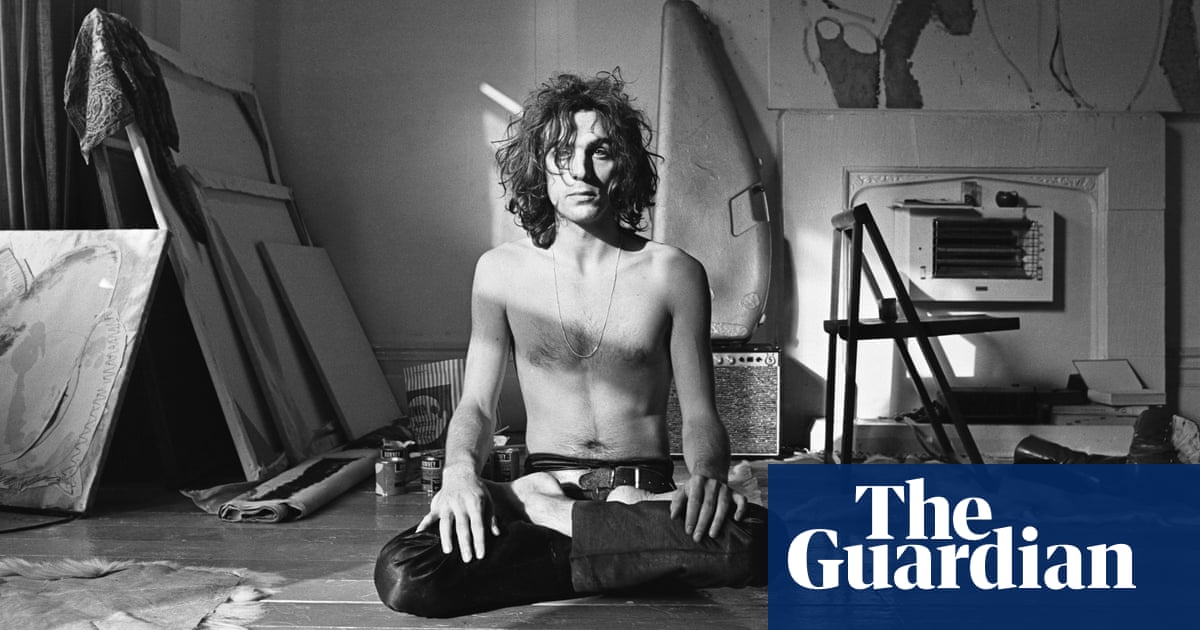

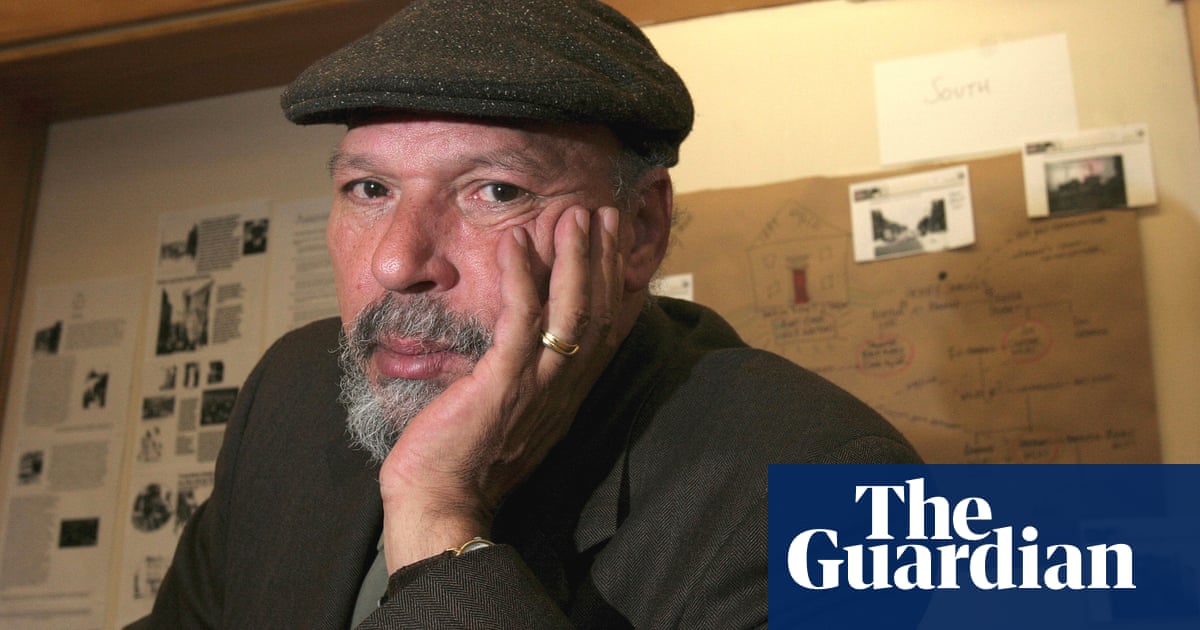

The secondary focus of Rossi’s documentary then becomes Warhol’s efforts at passing, not as a straight man per se, but as artist Glenn Ligon puts it, “the right kind of gay … a nice artist, acceptable gay.” In his immense fame, Warhol had faced relentless questioning of his personal life – “What do you think about sex?” – and in response, he distanced himself from his sexuality entirely. Despite the homoerotic imagery rampant throughout his work, he was able to convince enough people that he didn’t think about sex at all.

“The way he presented himself was as asexual,” recounts Fab Five Freddy. “You would hear rumors, but he publicly kept that aspect of his life out of the picture.”

The artist spent his life building a glamorous persona, “almost to shield himself” from a litany of gnawing insecurities, says curator Jessica Beck of the Warhol Museum. (As she’s speaking, she’s shown handling the artist’s trademark silver wigs, which he wore out of shame over his receding hairline.) To assuage his incessant fears of ageing and falling out of relevance, Warhol surrounded himself with the young, beautiful, or powerful: following his creation of The Factory in the 1960s, he befriended Keith Haring and Basquiat in the early 80s, just as the meteoric rise of their careers coincided with the decline of his. Early on in his relationship with the Waspy Jon Gould, he also briefly dressed in stylings of the 1981 bestseller The Official Preppy Handbook, a guide that allowed countless rust belt gay men like Andy to pass for middle class.

“Within the diaries,” according to Beck, “there are these moments when the performance lapses.”

From 1976 to 1987, Warhol would call his longtime friend Pat Hackett on weekdays at 9am, recounting the details of the day before. His intention was mainly to record his expenses for his tax auditors, but what emerged were invaluable glimpses into his honest, private mind. Entries range from mundane accounts of dinner parties – “The first course was crab meat and tomato aspic. You don’t see things like that any more” – to the anxieties that overtook the queer community during the HIV/Aids epidemic. “I wouldn’t be surprised if they started putting gays in concentration camps,” he wrote.

Two years after Warhol’s death in 1987, Hackett published these notes as The Andy Warhol Diaries, the source material for the documentary. Despite Rossi’s access to Warhol’s innermost thoughts, mysteries remain where the artist lies or omits information for various reasons. (Gould, for example, had forbidden Warhol from referring to him in his diary, and insisted to his own friends and family that they had a non-sexual relationship.) Filling in the blanks, the documentarian’s talking heads provide what often amounts to speculation – conflicting ideas of how deeply queer themes can be read in his final body of work, or whether Warhol is a suitable gay icon at all. “He wasn’t the protest-march gay, you know, the lobbying Congress gay,” says Ligon. Much of the language of Warhol’s time is problematic today, including his references to Basquiat as “the big black painter” or Aids as “gay cancer”.

What is undeniable, however, is Warhol’s impact on popular culture. “The key to Andy Warhol is reinvention,” Rossi says. “In the sort of pain of not being happy with what we are and the aspiration to be something bigger, he gave people permission to become another version of themselves.”

The Andy Warhol Diaries is available on Netflix now