There was an English exam under way when news began to circulate that the Taliban had reached Kabul. Panic spread and Yamna was among the students who never finished that exam paper – and never returned to school.

Six months on, the 16-year-old has barely left her house and says she feels very low, wondering whether she will ever be able to finish her education, or what job prospects she has in a country ruled by a conservative, male-only government.

Since August, secondary school girls from grade 7 and up have effectively been banned from education. While the Taliban claims the restrictions are temporary, saying they want to create the right Islamic environment for girls to learn, Afghanistan remains the world’s only country where girls are barred from education.

Kabul pharmacist Mohammed Mohibullah says that while the overall sales of antidepressants and sleeping pills have gone down, the number of women buying such medication has increased. “Since the Taliban’s takeover, it has been mostly peaceful. The war has stopped and there have been fewer attacks. But what I’m noticing now is a sharp rise in women asking for antidepressants, stress relievers or sleeping pills, even without a specific prescription. They are under a lot of pressure. While many men tell me they feel more at ease compared to before, it is the opposite for women and girls.”

Medical professionals in the country warn they are seeing a rise in depression among teenage girls. “Afghans – especially girls who have been at home for the past months – are confronted with an even more uncertain future than before. For many, this has fostered stress and hopelessness, which has caused depression to rise. Many feel as if they have lost control of their dreams, goals – their lives,” says psychologist Rohullah Rezvani, adding that, with society still largely stigmatising mental health, most Afghans never seek professional help and are often left struggling for years.

“People will admit to ‘having problems’ and might even take medication to calm stress levels, but that’s about it,” Rezvani says.

Muska, an ambitious 15-year-old who one day wants to pursue medical studies, says she has “lost hope”.

“We always lived in fear of daily attacks, but for me, not going to school and not knowing what my future holds is still worse,” she says. “I was nearby several explosions, with one of them being a close call. It was scary, but I always had hope that the situation would eventually improve and that there could be a future where girls and women have equal rights and opportunities. The Taliban have robbed me of that hope,” she says from her Kabul home, which she has barely left since August. “When they first announced the ban, I couldn’t stop crying. I felt paralysed. Living without purpose makes my life meaningless.” For months, Muska has spent her days doing little but watch television. “I can’t even get myself to study and I haven’t seen any of my friends. For what kind of future anyway?”

The Taliban say girls will eventually be allowed back to school. Deputy minister of culture and information, Zabihullah Mujahid, says the group is “not against education”, even though girls’ schools across Kabul remain closed, with just a few provincial schools remaining open to girls.

“The policies pursued by the Taliban are discriminatory, unjust and violate international law,” says Amnesty International’s secretary general, Agnès Callamard, urging the reopening of all secondary schools to girls. “Across the country, the rights and aspirations of an entire generation of girls are dismissed and crushed.”

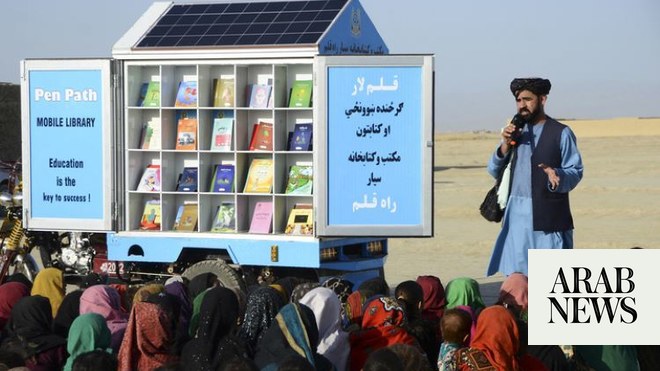

Teachers and activists have already opened ad hoc schools, similar to the secret schools of the previous 1996 to 2001 Taliban regime. Gatherings are mostly held in people’s homes. Laila Haideri, who runs one of the schools, teaching English and computer science, says she hopes it will help counter loneliness and foster ambitions many girls might have lost. “Regardless of what the Taliban decides and what the future holds, we will not let our girls stop learning,” she says.