Over the last fortnight, Russians have risked fines, prison terms of up to 15 years, physical abuse and more to express the belief that their country’s invasion of Ukraine is not in their name. At time of writing, 13,789 protesters have been detained since 24 February. An observer scrolling Twitter or watching the detainee count ratchet up might think that the anti-war movement could threaten Vladimir Putin’s aggression in Ukraine. But the reality on the ground looks different: the anti-war movement is small, weak and faces serious obstacles.

While the number of detentions is striking, it should not be confused with high turnout, because the detention rate is likely much higher than in normal conditions. Photos suggest that in many cities, the number of people at demonstrations is a few dozen or few hundred at most, with turnouts in Moscow and St Petersburg probably in the thousands.

When it comes to protest, size matters. A larger protest is generally safer to attend, as the individual risk of repression usually drops as the turnout climbs. But size is also essential to achieve visibility, which communicates a message to the public. Protests could play an important role in communicating opposition and even information about the war to the Russian public. But given the extraordinary increase in media censorship, the sudden eradication of independent media, the throttling of key social networking sites, and extensive use of propaganda, these protests are more visible to audiences in the west than to the Russian public at large.

The protests are also far too small to disrupt the status quo – another key measure of a protest’s effectiveness. An oft-cited statistic from Erica Chenoweth and Maria J Stephan suggests that non-violent movements are most likely to be successful when 3.5% of the population joins the protests. For Russia, that number is around 5 million people. Even if turnout in Moscow reaches the hundreds of thousands, there is little reason to believe that Putin, an isolated autocrat whose legacy now hangs on this war, will submit to their demands.

Why aren’t these protests larger?

Although many Russians are against the war, others are barely aware of it. Most Russians receive their news from state media, which is under strict instruction to refer to Russia’s actions in Ukraine as a “special military operation”; using the terms war, attack or invasion is now a crime. Though it is difficult to estimate what share of Russians believe the state line, misinformation and propaganda are incredibly widespread.

The political opposition has been decimated in the last few years and is unable to coordinate an anti-war effort. Following the January 2021 protests in support of Alexey Navalny, his organisations were declared extremist and functionally eliminated. Other opposition political parties with national reach, such as Yabloko, are exceedingly unlikely to chance severe penalties for organising illegal protests, or expose their followers to repression.

For individual activists, the landscape is also bleak. Many oppositionists are in self-imposed exile, and lack both the social media reach and the moral authority to call for protest. Those in Russia are rapidly repressed, such as human rights activist Marina Litvinovich, who was arrested on the day of the invasion, a few hours after she posted about protesting. The repressive landscape is changing rapidly, with new consequences for speaking out introduced seemingly on a daily basis, and many potential protesters have already begun leaving the country.

As a result, there is no “anti-war movement” as such in Russia. The protests happening across the country have no coordinating body. Many have been planned through personal networks and social media posts. In some cases, opponents of the war have simply travelled to their nearest city centre in the hope of finding like-minded citizens. Many protests are single-person pickets.

Although the Russian anti-war movement is not currently looking likely to change the course of the war, that does not mean it will have no effect. Repression often leads to innovation in protest and new leaders and organisers may emerge. For instance, soldiers’ mothers, a group with a long history of political activism in Russia, may organise against the mistreatment of troops.

As the consequences of sanctions are felt across society, more Russians may oppose the war. Demonstrations against specific economic grievances such as wage arrears, inflation and declining pensions have been common under Putin. Yet Russians also exhibit a tendency to put their heads down when the economy sours, as they did during the economic downturn that followed the 2014 seizure of Crimea.

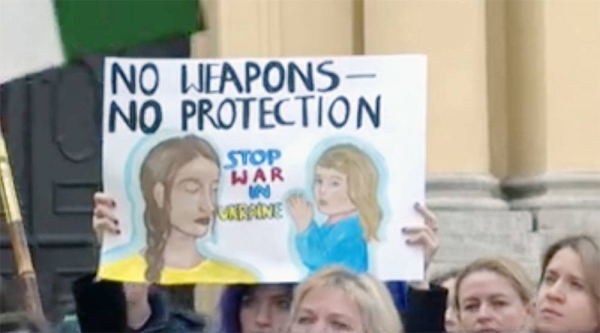

Even if anti-war protests remain small, they prove to the world that Putin does not represent the will of all Russians.

Sasha de Vogel is a post-doctoral fellow at the Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia, New York University