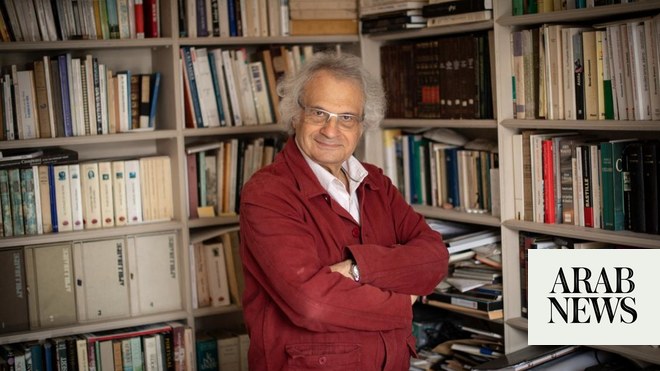

On International Jazz Day, Arab News talks to the French-Lebanese virtuoso who has taken the genre in new directions

DUBAI: For a man who has released 16 albums; packed out venues from Paris to New York, performed with Sting, Juliette Gréco, and Jon Batiste, among others; is managed by legendary American producer Quincy Jones; and has become France’s leading trumpet virtuoso, French-Lebanese musician Ibrahim Maalouf has a strange relationship with the instrument that has made him internationally famous.

“I grew up playing the trumpet, because my father (Nassim) was a trumpet player. But I didn’t like it,” Maalouf tells Arab News from his home in the suburbs of Paris.

“I know it’s strange to say this now, given everything this instrument brought me. It might sound a little bit rude to my father, but I have to be honest,” he continues. “I used to play classical music with the trumpet and my father used to play it very loud. He loved the trumpet. . . I loved the piano and used to play it all the time. When I had to play the trumpet, it was really not a pleasure. Mostly, it was because its sound hurt my ears. My father used to play with high notes to show that you were strong. I wasn’t like this at all — I was very shy and intimidated by all of it. I didn’t identify with his kind of playing.”

Maalouf was born in Beirut in 1980, five years after the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War. “My mother was giving birth to me in a hospital that was being bombed,” he says. They immigrated to France “right away,” intending to stay only until the situation in Lebanon cooled down. They haven’t lived in their native country since.

“My father left Lebanon when he was 24 years old. He was a farmer in the Lebanese mountains. He didn’t know anything about French culture but he loved the trumpet so much. He left everything behind to go to France, where he didn’t know anyone,” Maalouf says. “He wanted to become a trumpet player and a classical musician; I didn’t at all.”

We are speaking ahead of International Jazz Day, celebrated yearly on April 30. For Maalouf, who was raised listening to Arabic and Western classical music, hearing jazz for the first time in his teens was a real turning point.

“I bought a Miles Davis CD and I just listened and. . . boom! I thought, ‘We have the right to play the trumpet with soft notes, something that whispers like a human voice.’ Everything changed for me,” he says. “I started to listen to Chet Baker, Jon Hassell, and Miles, of course. They played the trumpet in a way I thought was forbidden. This was why I loved jazz — experiencing people playing softly and whispering on their instruments without having to sound aggressive.”

Maalouf views jazz as the “music of freedom” and is quick to dismiss purists who reject experimentation in the genre.

“They love it so much that they are scared by the fact that it might change with time and become something else,” he says. “The thing is, culture is made to be transformed with time.”

His repertoire often incorporates elements from Arabic music, including the deep tarab and slow, sentimental mawaal. To achieve this sound, he plays quarter tones — notes found in Arabic music, but not Western — on a special trumpet invented by his father that has an extra valve. “It’s my culture,” he says. “This is how I express myself.”

Maalouf is renowned for putting a surprising, unique spin on classics such as Umm Kulthum’s 1969 hit “Alf Leila Wa Leila” — which he performed with a jazz quintet on his 2015 album “Kalthoum.”

“People told me, ‘You’re touching a traditional melody. You’re going to harm it. Don’t change it; people are going to be mad at you.’ And I was, like, ‘Why? This melody is so beautiful, I’m shaping it differently.’”

During Bastille Day celebrations in 2021, at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, he put his own twist on “La Marseillaise” — the French national anthem — taking the traditionally bombastic song at a calmer, soothing pace. He knew his interpretation would stir up emotions. “Obviously, we’re going to get bashed on Twitter,” he said in a video on his Facebook page at the time. “If that’s the price to pay, it’s my pleasure.”

Maalouf is often described as a musician who “bridges two worlds” (or similar) with his music. It’s a description he doesn’t agree with.

“I don’t see myself as someone who brings Middle Eastern culture and jazz together,” he explains. “I just see myself as a random person, who had the chance to be taught how to play music and who is (painting) with music a picture of the times we’re living in. I don’t even care about mixing jazz and the Middle East — it just mixes naturally. I’m just a witness to the natural mix that is made by humans all over the world. Thanks to the Internet — and we are the Internet generation — this is everywhere.

“I understand that to market music, you have to name it,” he continues. “But when it comes to the music itself, this is where we have to be very careful. Why do we have to reduce everything we are, you are, and I am to just being ‘an Arab living in France’? Do we have to name us, name cultures? You name a culture and one second later it’s something else.”

He offers an example of the ‘natural mix’ he is talking about. “When I was at the Lincoln Jazz Center in New York, I was playing in front of jazz lovers and they were listening to Umm Kulthum’s melody and they were like, ‘That’s so cool’. You see? We share the same melodies, it’s just a question of how you shape them.”

Maalouf defies attempts to categorize him or his music. He composes film scores. He produces rap albums. He is interested in hip-hop culture. “The older I get, the music I’m listening to is getting younger,” he says. “I’m like a researcher in a lab, working with tubes and chemicals — and I get interesting colors and textures. I’d rather be defined as an experimenter.”