This week’s 25th annual St. Petersburg International Economic Forum was originally scheduled to be a big anniversary celebration, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means the bottles have been put on ice.

The event, which runs from Wednesday to Saturday, has previously been a major networking forum, akin to a Russian Davos. The 2018 summit enjoyed perhaps the biggest international lineup since before 2014 — when Moscow was hit with sanctions over its annexation of Crimea — with keynote speakers including French President Emmanuel Macron, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde. According to the Russian authorities, some 500 new business agreements worth about $38 billion were signed.

This year will be different, with visitors reportedly including an Afghan Taliban representative, the investment minister from Myanmar’s military government and the head of Venezuela’s central bank. These are all heavily sanctioned countries. It has also been reported that some business tycoons are worried about being seen attending the forum because of the threat of Western sanctions, while other executives have apparently requested that organizers remove their names from their badges so they cannot be identified.

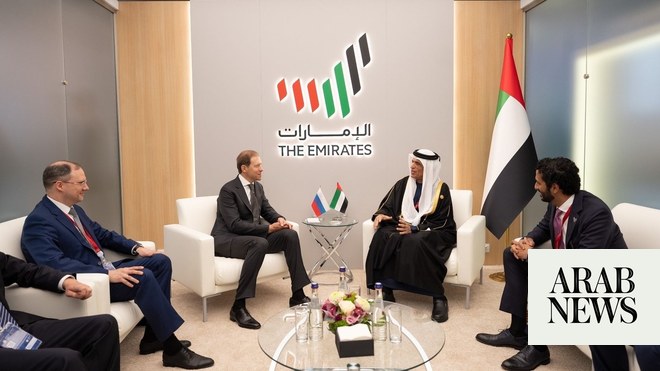

The forum’s program lists the CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia as speaking, while senior figures from the French-Russian and Italian-Russian chambers of commerce and industry and the Canada Eurasia Chamber of Commerce are also taking part in discussions. Moreover, there will be business representation from nations in the Middle East and Africa.

However, the bigger picture is one in which the Ukraine war has changed the contours of international sentiment toward Russia, both politically and economically. Indeed, the period since Moscow’s invasion has been dizzying for business in what Yale University Management School’s Jeffrey Sonnenfeld has called an “unraveling of capitalistic diplomacy,” as commercial relationships have been severed on a scale that was unimaginable as recently as February.

Driven in part by the tougher sanctions regime, some 1,000 multinationals have already cut or reduced their business ties with Russia. They have done this by: Withdrawing; suspending (temporarily curtailing operations while keeping return options open); scaling back; and/or buying time (postponing future planned investment while continuing substantive business). At the time of writing, there are now fewer than 250 multinationals that have not exited or reduced their activities, according to the list compiled by Yale University.

The scale of the change is huge, raising key business questions such as: Is economic globalization now in permanent reverse? While such economic issues will be the main official topics being discussed in St. Petersburg, perhaps the key question on the minds of many will be a political one: How will the war ultimately end?

The conflict’s outcome remains very uncertain and it appears unlikely that either side will win a decisive victory imminently. That is, for as long as Moscow is prepared to expend massive resources in the pursuit of its so-called special operation and Ukraine continues to be supplied by the West (the US, for instance, has already committed more than $50 billion to Kyiv, which is more than the entire Australian defense budget).While the Russian military was ineffective to begin with, it now controls about 20 percent of Ukraine (an area the size of Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands combined). It remains possible that the war may yet shift further in Moscow’s favor and that it could seek to try to end the conflict relatively soon by pocketing its territorial gains and declaring a “victory,” with the Russian-backed separatists in the Donbas protected and a land corridor to Crimea established.

Overall, the level and range of risks in Ukraine remain exceptionally high. This is partly due to the fact that Moscow’s exit strategy is not clear and it may yet miscalculate out of frustration. Moreover, it is now the announced strategy of the Western alliance led by the US to try to inflict a defeat on Russia — a key difference from previously in the postwar era that raises the stakes even further.

The most likely outcome in the coming weeks is a war of attrition. Moreover, even if the major fighting ends in 2022, there looks likely to be periodic tensions between Russia and Ukraine for a long time, which could see significant market volatility continuing into next year.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.