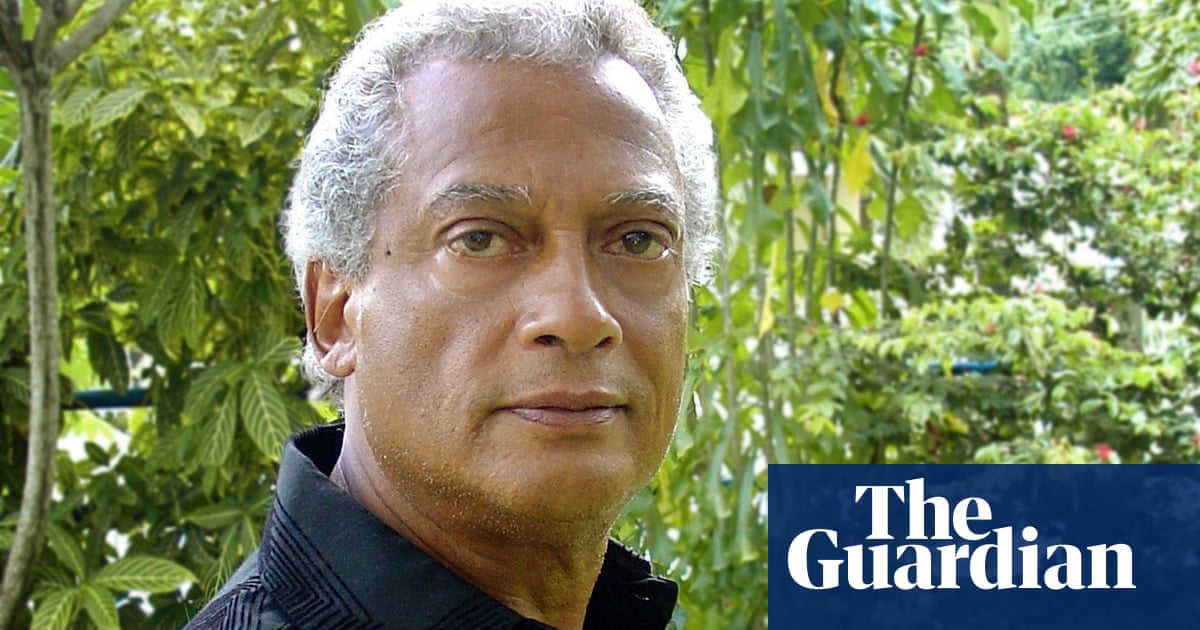

Later this week, my friend and mentor Horace Ové will head to Buck House to be made a knight of the British empire. Those of us who know Horace rejoice at this richly deserved honour. We are also amused by the deep irony. For the very empire that will anoint him is the same one that Horace – throughout his six-decade career as a pioneering film-maker, writer, painter and photographer – has held a mirror to and been a fierce critic of. It is all so very Horace.

Known as the godfather of black British film-making, having directed the first black British feature – Pressure – in 1976, Horace was also the first to document the arrival (and importance) of reggae to the UK with 1971’s Reggae. Shortly after, King Carnival told the story of the Trinidad carnival, while 1978’s Skateboard Kings chronicled the birth of the new sport.

If Horace has a style, it would sit somewhere in the reportage school. He is a documentarian at his core. His camera rarely intrudes. He sets it up to bear witness. He wants his subjects to speak for themselves, to reveal the complexities of their lives. “I’m interested in people that are trapped,” he once said. “The trap that we are all in and how we try to get out of it.”

In his depictions of this battle, Horace has been resolute and fearless. Pressure is the story of a Windrush family trying to come to terms with life in Britain. Told primarily through Tony, the first member of his immigrant family to be born in the UK, the film showed the forces at play on black boys stepping into manhood in 1970s Britain. So searingly authentic was the film, it was effectively banned for almost three years. The scene at issue portrayed police brutality and Horace wouldn’t cut or re-edit it for its funder, the British Film Institute. He waited it out and fought for his vision. He won.

As a photographer, Horace chronicled the growth of black British consciousness and political awakening in 1970s and 80s London. He was in the room, an active participant, a voice around the table alongside Stokely Carmichael, Darcus Howe, Michael X, John Lennon and others. With cameras rolling, or his trusted Nikon SLR slung between his neck and armpit, Horace, more than almost anyone else, has documented the black British experience from the front line. His photography is always active: there is nothing passive in the situations he captures or the faces he shoots. His search, he says, is for “the reality of a moment in a person’s life”.

There is no truer example of this than Horace’s shot of Michael X – a major voice in the British black power movement – and his entourage walking along a platform at Paddington station. Horace captures them in step and in formation around Michael X, all clad head to toe in black and wearing dark glasses. You can feel their swagger, the defiance in their walk, their pride and their strength. Also, in the faces of the white man and boy watching them pass, Horace shows the fear they engendered.

I first met Horace when he cast me in The Orchid House, his 1991 adaptation of Phyllis Shand Allfrey’s Caribbean saga for Channel 4. Told through the eyes of Lally, the family nanny, the series captured the decline of a once wealthy white family in Dominica between the first and second world wars, and the black people who interacted with them. The job was a profound one for me. It was my first major TV role out of drama school and the longest time I had spent in the West Indies. I had become a young father just four weeks before we started shooting and Horace took me under his wing. I don’t know why. Maybe it was our shared Trinidadian heritage. Maybe he could just see what I needed.

Horace directs like he is hosting a party. That’s what I remember most about working with him, the laughter and the long hours. His notes come as if he is sharing a joke or telling you where the good rum is. I remember shooting a scene where my character was speaking to a crowd about the need for Dominican workers to unionise. Horace’s note after a few takes was a question: “You ever take the floor with your boys at a dance?” I knew what he meant. He knew I would.

Horace has been my Obi-Wan for over 30 years. I rely on his guidance so much that when I need to have a chat with myself, the other voice in my head sounds a lot like his. Over the years, I have met a good few people making strides in film, TV and theatre in Britain, who sought out Horace and sat at his feet. So many of us consider him our inspiration. He was one of the first to crack through the glass ceiling and he did so with others in mind. Whether we follow the same path he laid out for us or not, when we look down, his footprints are there. Arise Sir Horace, a true knight.