The tension in the air was palpable as the group of television producers waited with bated breath to see what would happen as the Siberian tiger crept into the bear’s cave. This was a groundbreaking moment in the making of wildlife documentaries, and one that will be seen by millions who tune into Frozen Planet II.

It took three years of persistence and trial-and-error filming in Russian forests using remote cameras to get the footage of the tigers entering bears’ caves, said Elizabeth White – who worked on the original Frozen Planet and produced the award-winning “iguanas vs snakes” episode of Planet Earth II.

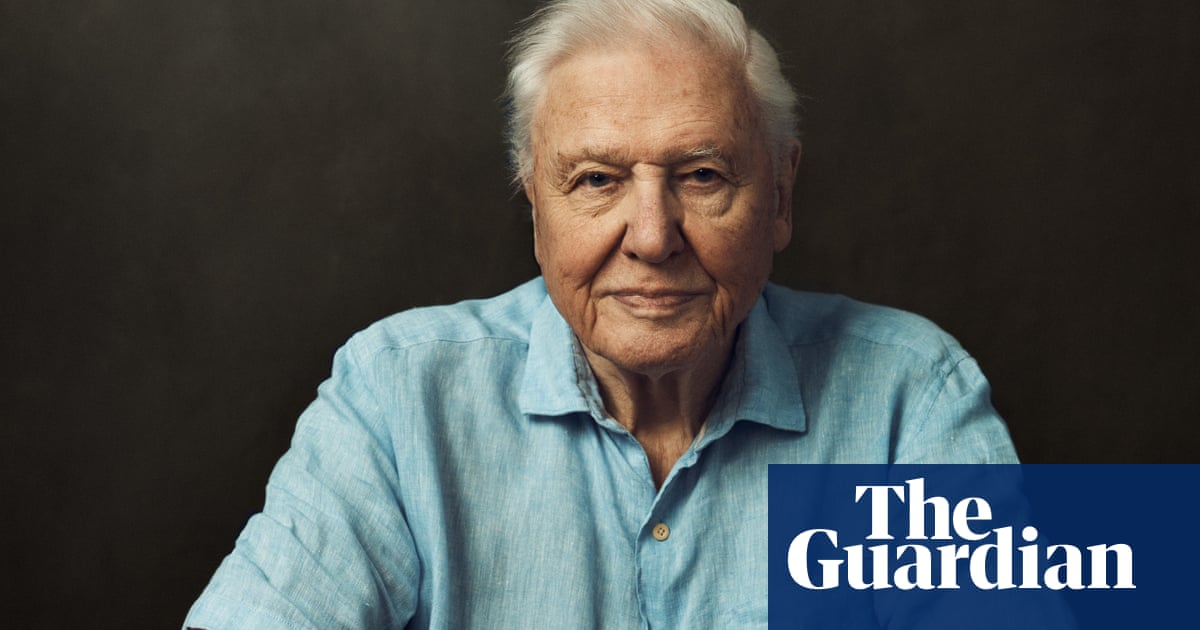

The tiger footage captured such a unique moment, it even took David Attenborough by surprise. White told the Observer that, after hearing reports that tigers sometimes caught hibernating bears, catching this on film was “a labour of love” and “seemed like finding needles in a haystack”.

“We completely failed the first year, so we shifted our location in season two and got some lovely shots – but no real substance. Then a local photographer said to us that our cameras were too big – the tigers are seeing them. We looked at the technology he was using, and sure enough the tigers were detecting the larger cameras.”

By then, “technology had moved on”, said White “and we were able to get a smaller camera that was high enough resolution, and we managed to get footage of tigers entering the caves.”

She said that Attenborough was “particularly wowed” with this footage of tigers and leopards. “We filmed both species using the same trails within the same forest, which he was fascinated to see,” she said.

He also “was very excited” by other scenes in the six-part series including killer whales creating waves to wash seals off ice floes, film of an Arctic bumblebee captured in her dark snow hollow using a probe camera, and an avalanche in the Canadian Rockies filmed, for the first time according to White, by a racer drone – a tiny new drone that has a 360-degree camera and is controlled by a headset and goggles.

“We got a team of young guys who normally throw these drones down mountains chasing snowboarders, and they were game for having a go at trying to capture avalanches,” she said. “It’s one of the most thrilling pieces of footage I’ve ever seen of a landscape.”

The 96-year-old Attenborough is renowned for his interest in new technology and “gets very excited by drones”, said White. “That was all new and exciting to him. He likes the stories he’s not heard before, and it’s unusual to find one because he’s been everywhere and seen everything.”

Technology has transformed documentary-making since the first Frozen Planet, she said. “When we filmed the original series about 11 to 12 years ago, it was all sort of pre-digital; some of it was still being shot on tape. The technological advances over the last 10 years have been enormous.”

She said that remote cameras and drones are allowing natural history crews to gain “insights into new behaviours and [have] the ability to film in landscapes where you would never be able to get a helicopter.”

“In the mountains of China, we put small cameras above the snow line to capture wild panda footage in winter. We’ve got some charming footage of a male panda coming in, and he sticks his bottom in the air and rubs it on a tree: it looks like he’s twerking or something.

“Obviously, you’d never get that normally – you couldn’t put a cameraman in a hide for all the months it took to capture it.”

Other highlights include rare footage of male and female teen polar bears playing together on the ice.

Advances in cameras, including “weatherised, cold-adapted cameras that you can put on the side of glaciers to help document climate change”, are giving viewers new insights into the crisis facing our planet, she added.

The production team and crew faced numerous challenges during the four years of filming Frozen Planet II, from making cameras polar bear-proof by running cables through scaffolding poles to trying to make tiny cameras indestructible to New Zealand alpine kea parrots who winkled them apart (“one completely trashed one of our cameras,” said White).

Other trials included cameramen having to spend 10 days at a time acclimatising on an ice cap in Peru in order to change batteries on cameras, having to keep the batteries warm under their clothes, and camping on ice floes in the Antarctic while trying to stop melting through to the icy seas below.

But the effort is likely to be rewarded by huge audiences and to help raise awareness of climate change and our changing world, as other BBC nature documentaries have done over the years.

Friends of the Earth’s head of policy, Mike Childs, said: “The BBC’s fantastic natural history programmes have been beaming the marvels of our planet into our homes for decades, and allowing us to temporarily escape to magical places we often know little or nothing about.

“Importantly, they have not only helped raise awareness about the beauty and wonders of our natural world, they have also alerted us to its fragility and the myriad threats it faces.”

Childs pointed out: “The stark and heartbreaking images in Blue Planet II not only highlighted the dangers plastic pollution poses, they also sparked a huge public outcry which forced the government and companies to take the issue far more seriously and act on unnecessary plastic.”

Frozen Planet will air on Sunday 11 September at 8pm on BBC One.