If, despite the slide in sterling, I had had a pound for each time that someone had told me over the past two and a half years how disappointed they were with Keir Starmer (to which I have mostly retorted that he seemed to be playing a long game rather skilfully), I would be well placed to pay my energy bills this winter with some ease.

I am not sure these old arguments about Starmer will provide a productive income stream for much longer. The combination of last week’s catastrophic unfunded tax cuts and a solidly successful Labour conference has begun to generate a new consensus that Starmer is moving closer to power. The International Monetary Fund’s warning – greeted on the right as further proof that all international institutions are out to get them – tightens the knot a little further. The next election may now even be Labour’s to lose.

It bears repeating that, after what happened in the 2019 election, this is an extraordinary possibility and turnaround. Labour needs to win about 130 seats to have an overall majority next time, with a swing bigger than the one achieved under Tony Blair in 1997. Take Scotland out of the equation and Labour requires a bigger swing in England and Wales than in Clement Attlee’s 1945 victory. The proverbial mountain that Labour needs to climb is as high as ever.

It also needs stressing that the next election will not come soon. It will most likely be in 18 to 24 months, and a lot can change in that time. Liz Truss is a ruthless politician who should not be underestimated simply because she is presiding over the worst market crisis under a Tory government for 30 years. And Labour is always capable of throwing away a midterm lead.

Even so, the events of the past few days have helped crystallise a sea-changing sense that the country needs and is ready for a new government. It is a big moment. For those of us old enough to recall those times, it has something of 1995-6 about it, and also of 1963-4. But the past is no predictor of the future: Labour’s win in 1997 may have been a landslide, but the 1964 victory was an absolute squeaker.

The 2024 election will be fought in a different Britain from either. This was neatly summed up by the comfort with which Labour said it would reimpose the 45p top rate of income tax, abolished by Kwasi Kwarteng last week. That wouldn’t have happened under New Labour in the tight fiscal conservatism of the 1990s. But it has happened in the 2020s because, after Covid and the energy price explosion, the public debate about spending and taxation is simply in a different place now.

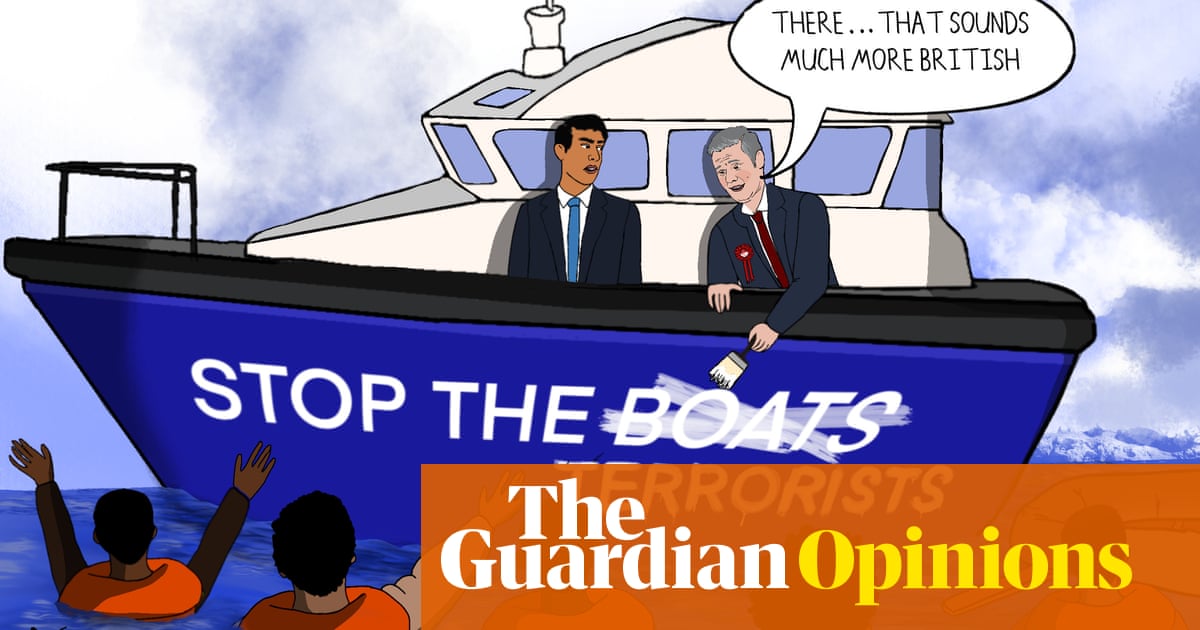

The possibility that Labour may win it is not solely down to the chaos and division that has overtaken the Tory party. A lot is Starmer’s doing, too. The Liverpool party conference was a vindication of his priorities since becoming leader in 2020: first, the repudiation of the Corbyn era and the renewal of the party’s patriotic credentials; second, the long reforging of trust in Labour’s economic competence and values, and this week, a forward-looking grasp of the climate and energy crises.

Starmer is a very methodical person. As a lawyer, he built his reputation not on dazzling courtroom displays but on patient scrutiny of the strengths and weaknesses both of his own case and that of his opponents. He was always good at thinking logically and long, at working out in advance where the crunch in a contest would come, and at preparing a case that would allow him to seize the advantage when the right time came.

This is his approach to politics too, and it is hard to argue now that it is not working. The conference has been light years away from the tensions and suspicions of the recent past. The national anthem on Sunday embodied the left’s current eclipse. Rachel Reeves’s economy speech, albeit in front of the open goal provided by Kwarteng, confirmed her as the leader’s most important lieutenant. Meanwhile, the Great British Energy plan provided real substance to the party’s “fairer, greener” conference pitch.

There were other, less obviously headline-generating descants, too. The priority on energy in Starmer’s speech allowed him to consolidate Labour’s increasing advantage among younger, greener voters. The conference’s success gave impetus to the anti-nationalist offensive the party needs to begin in Scotland. The carefully phrased remarks from Reeves and Starmer on “making Brexit work” were another important advance, creating space for a less confrontational relationship with Europe.

Liverpool was also a success in party management terms. Internal party elections went Starmer’s way. There was minimal speculation about alternative leadership challengers, such as Andy Burnham, Angela Rayner or Wes Streeting. The unions cooperated with the leadership most of the time. And the conference vote in favour of electoral reform means the issue is back on the table without Starmer needing to say anything much on the subject – but watch this space.

In the end, though, Starmer also proved to be an incredibly lucky general. Kwarteng has gifted him a definitive demonstration of why surface cleverness in politics (at least as defined by the Tory press) is not enough. At one of those rare times when the public may notice, Starmer has responded with a textbook illustration of why thought, wisdom and judgment count for so much more.

It would still have been a successful conference week for Labour even without Truss, Kwarteng and the IMF. But to be presented with a once-in-a-generation, government-created sterling slide, bond market crisis, mortgage famine and a handout to the super-rich has helped transform Labour’s week from one of workmanlike advance to one that showered the party with a bonanza of political rewards. They may not endure, but it will all be very different with the Tories in Birmingham next week.

Martin Kettle is a Guardian columnist