Sitting on a mattress in an art gallery turned bunker in Kharkiv, with Russian munitions “howling and thumping” overhead, Dariia Selishcheva began making a video game. Jauntily titled What’s Up in a Kharkiv Bomb Shelter, it was an attempt at self-distraction that evolved into a work of journalistic “autofiction”. It offers a brief, vivid portrait of life under bombardment in the early months of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, based closely on conversations with Selishcheva’s neighbours in the shelter and correspondence with friends hiding elsewhere.

“My goal was to provide an opportunity for ordinary people’s voices to be heard, to capture a fragment of life in a shelter,” Selishcheva says. “I wanted everyone to know about their lives and thoughts.” Created using lo-fi Bitsy Color software, the game simply consists of walking around talking to fellow survivors, against a soundtrack of explosions, listless guitar and hushed voices.

Somebody is worrying about their missing grandson. Another praises their dog, who ran for the shelter as soon as the bombs began to fall (Selishcheva notes that evacuated Ukrainian cities are full of abandoned animals, many trapped inside apartments). There are gloomy jokes, and tentative efforts to make sense of the chaos. “When the war is too close, it’s hard to believe,” one person tells you, adding that, “The brain sees and analyses everything that happens, but it turns off the reaction.”

Some characters flicker different colours, “like lightbulbs that are about to burn out”, as Selishcheva describes them – a depiction of trauma inspired by not just the war, but another woman’s account of harassment. “I put myself in her place,” Selishcheva says. “There, inside it, I felt that I was at the same time, there and not there. Later I asked her if she was experiencing something similar, and she agreed. I spoke with a psychologist who helps people with PTSD, and she confirmed that victims of violence, until they heal from trauma, are in a quantum state, between existence and nonexistence. They have been treated like objects, so they lose their self-image, lose faith that they are free.”

Selishcheva is far from the only Ukrainian developer making a game in response to Russia’s struggling assault, which is dragging into its eighth month. Other projects include Zero Losses, by horror game studio Marevo Collective, in which you play a Russian soldier destroying the bodies of comrades to prop up the Kremlin’s official casualty figures.

Some of these games are more “lighthearted”, as Stepan Prokhorenko, one of the organisers of this year’s Ukrainian Games festival on Steam, explains. Ukrainian Farmy casts you as a tractor driver stealing tanks, while Slaputin is about whacking Putin with a sunflower. But even these “therapeutic” plays are “weaponised” artworks, he says, devised by people who now split their days between their vocations and volunteering or active military service. “I believe that games are storytelling, and storytelling is how you make ideas survive,” Prokhorenko says. “The idea of a free and independent Ukraine is something that russia [sic] despises and wants to erase. So games become yet another battleground, in a way.”

This battleground extends to language. Prokhorenko always writes “russia” in lowercase (and requested that the Guardian do so when quoting him), and many Ukrainian developers are in the process of changing Russian words in their games for Ukrainian equivalents – Chernobyl has become Chornobyl, for example, in GSC Game World’s Stalker 2. “You have to remember that russia’s invasion of Ukraine began in 2014 [with the attack on Crimea], days after the Revolution of Dignity,” Prokhorenko goes on. “In the eight years since, that dignity is what we in Ukraine have been fighting as hard as we can to preserve. This is the reason I think it’s crucial for Ukrainian artists, including game developers, to continue doing what they do best and making art. Even in wartime, amidst all the bloodshed and tragedy, we choose not to lose our humanity.”

Among the most outlandish Ukrainian games about Russia’s war is Putinist Slayer, a side-scrolling shoot-’em-up featuring the grotesquely freefloating heads of Russian state figures and celebrities, with unearthly cameos from Elon Musk and Boris Johnson. Created by Bunker 22, an “avant garde” collective from across the country, it’s a viciously comedic piece of counterpropaganda, expressive of the idea that “ordinary humour has become inaccessible” to Ukrainians, in the words of the group’s anonymous lead developer.

“It’s like closing your eyes and thinking about something good when you have a maniac with a knife behind your back,” the developer continues. “But the mind needs relaxation, needs positive impulses. In the current situation, the only thing we can laugh at is our enemy, at his absurdities and failures. This laughter is life-affirming and goes hand in hand with our belief in victory; it is part of the core that allows us to resist the terror of Russia, and strengthens the power of our spirit.”

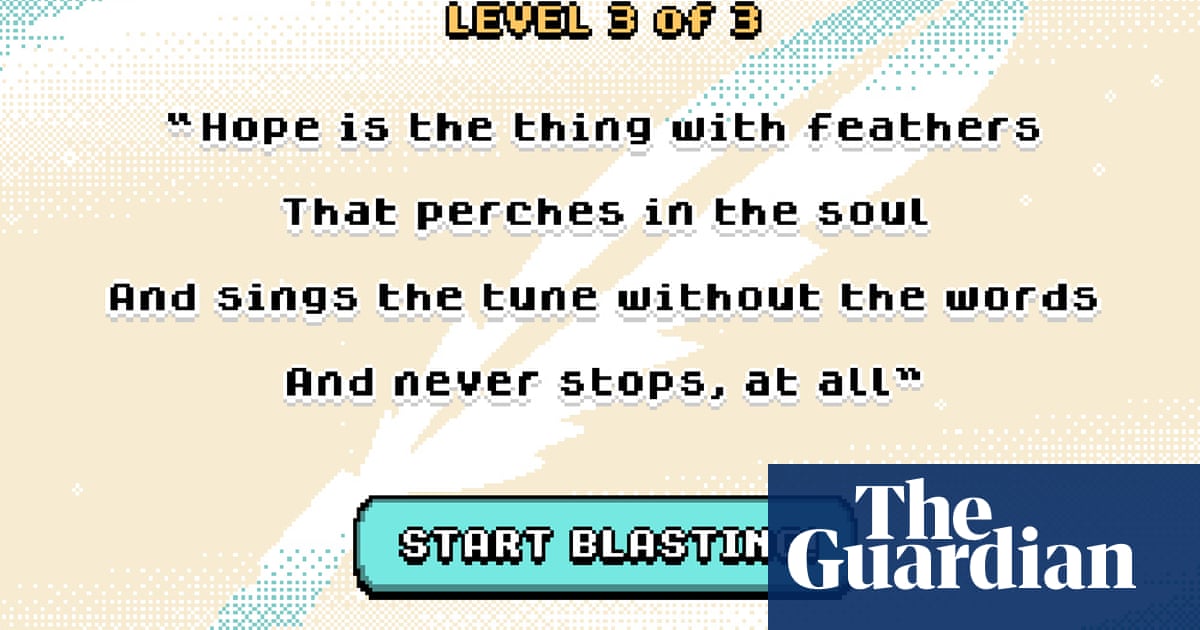

Putinist Slayer opens with a Star Wars-esque rolling preamble in which a drug-addled Putin has forged an alliance with evil aliens, obliging the player to travel into astral space to blast his minions, some of whom appear as flying orcs in reference to Ukrainian wartime slang. It’s an absolute bloody farce: one in-game notification tasks you with hunting down Putin’s teddy bear.

This is not just Twitter-style dunks, or gleefully dehumanising an aggressor that has branded its victims “Nazis”. The game’s backstory writing blends sci-fi with historical information. It aims to challenge the Russian state’s self-serving “editing” of Ukraine’s past and the “invisible poison of Russian media manipulation” elsewhere. It is both “a parallel fictional world that is more connected to today and the present than any other game”, and a punchy arcade shooter aimed at those who might be deterred by openly political art. “The truth is a natural disinfectant for propaganda,” Bunker 22’s lead developer observes. “But the problem is how to interest people in that truth and how to deliver it.”

Where some Ukrainian developers see their games as an extension of the war effort, others like Selishcheva seek only to pay witness. She is influenced by Anna Anthropy’s book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters, from which she has taken the principle of “democratising video games” by means of accessible development tools such as Bitsy. “The position of witnessing is democratic and simple: you cannot draw conclusions when it is too difficult to generalise,” she says. Unlike Bunker 22, Selishcheva feels the truth needs no elaboration, though there is “creativity” in “choosing which side of the world to highlight”, she says. “Just capture this fragment, and leave it to others. And don’t try to influence people’s minds – instead, just give them your experience.”

Selishcheva finished her game after evacuating to Lviv, where she now rents a small house with four others. Initially, life in Lviv felt like “a continuation of the situation in the shelter”, where “we constantly discussed politics, played board games and tried to support each other”. But this “cohesion began to fade” as the group adjusted to life in a relatively peaceful city. “Going for bread no longer required moral and physical preparation in order to quickly run to the nearest basement; being with each other was no longer a feat.”

At the same time, Selishcheva has met with “misunderstanding, aggression and guilt” from western Ukrainians who haven’t undergone the same hardships. She sees her project now as “a game primarily for us migrants: so that we would not forget what we learned”.

Again, language is an important consideration. Selishcheva’s game can be played in Russian, this being her first language – shunning the occupier’s mother tongue, as many eastern Ukrainians are now pressured to, has caused her a lot of stress. But the inclusion of Russian is also an attempt to engage Russian players who are themselves objects of Putin’s tyranny. The game includes a phone conversation with an unnamed Russian person, who insists that the description of the shelter is just Ukrainian propaganda.

“I messaged several of my friends in Russia, asking them the same question: ‘There is a war, I am in a shelter – what do you think about this?’” Three respondents were horrified by Selishcheva’s account and offered money to help her relocate. “The fourth was my great-aunt, [and] it turned out that she was firmly on Putin’s side. The words that are in the game belong to her.”

Selishcheva’s family are no longer speaking to her great-aunt, but her game has struck a chord, at least, with Putin’s internal opponents – it has been republished on Russian anti-war blogs. She argues that it is vital for any political artwork to reach out to the unconverted. “A person is not the same as their beliefs. Political views are not eternal. And before severing any ties with the Russians, you need to remember that these are people living in a poor country that has become one of the quintessential examples of totalitarianism in the 21st century. You shouldn’t demand much from them, but like any other people, they carry a responsibility. You can and should talk to them.”